Philippine Supreme Court's March 2006 decision dismissing Judge

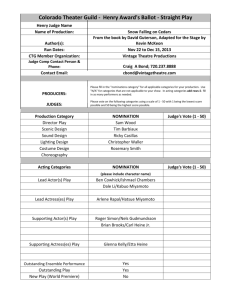

advertisement