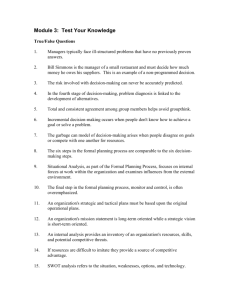

Success Criteria within Corporate Diversification

advertisement