duane hanson - Serpentine Galleries

advertisement

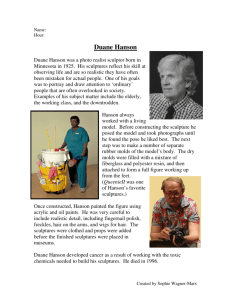

Press Release DUANE HANSON 2 June – 13 September 2015 Serpentine Sackler Gallery Self Portrait with Model, 1979 The Serpentine presents the work of late American sculptor Duane Hanson (1925-1996) in his first survey show in London since 1997. Throughout his forty-year career, Hanson created lifelike sculptures portraying working-class Americans and overlooked members of society. Reminiscent of the Pop Art movement of the time, his sculptures transform the banalities and trivialities of everyday life into iconographic material. The exhibition at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery presents key works from the artist’s oeuvre. Hanson’s early works comprised life-sized tableaux – depicting soldiers killed in action, police brutality and homeless people – that confront the viewer with devastating truths. Widespread criticism of his work Abortion in 1965 encouraged Hanson to formulate his social and political views as sculptures. In the following years, and in the spirit of protest movements of the time, he created sculptures that dealt with social misery and violence. From the late 1960s his work shifted to depicting everyday people, with some satirical aspects, creating figures that could be conceived as representative of an entire labour force, class or even a nation. Beginning with Football Players in 1968, Hanson produced sculptures that represent typical Americans, concentrating on “those that do not stand out”, including Man with Hand Cart (1975), Housepainter (1984/1988) and Queenie II (1988), all of which are included in the Serpentine exhibition. The hyper-realistic nature of the sculptures results directly from Hanson’s artistic approach. Using polyester resin, he cast figures from live models in his studio, paying attention to every detail, from body hair to veins and bruises. The sculptures were assembled, adapted and finished meticulously, with the artist hand-picking clothes and accessories. Julia Peyton-Jones, Director, and Hans Ulrich Obrist, Co-Director, Serpentine Galleries, said: “Duane Hanson’s iconic sculptures of ordinary people will literally stop visitors in their tracks this summer. Beyond the stunning realism, the power of Hanson’s work lies in his unwavering focus on and sympathy for the human condition.” To accompany his exhibition at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery the Duane Hanson Estate has generously given 10 original Polaroid photographs which feature a mixture of the original models used to inform a number of Hanson’s most notable pieces, and the pieces themselves installed in the artist’s studio. For more information, please visit serpentinegalleries.org/shop The summer season at the Serpentine includes the concurrent exhibition of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s paintings at the Serpentine Gallery, the 15th birthday of the Serpentine Pavilion commission, which opens to the public on 25 June and the Park Nights series of live events. For press information contact: Miles Evans, milese@serpentinegalleries.org, +44 (0)20 7298 1544 V Ramful, v@serpentinegalleries.org, +44 (0)20 7298 1519 Press images at serpentinegalleries.org/about/press-page Serpentine Gallery, Kensington Gardens, London W2 3XA Serpentine Sackler Gallery, West Carriage Drive, Kensington Gardens, London W2 2AR Note to editors: Duane Hanson was born in 1925 in Alexandria, Minnesota, and died in 1996 in Boca Raton, Florida. Solo exhibitions include Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, Denmark, 1975; Des Moines Art Center, Iowa, 1977; Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 1978; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1979; Kunsthaus Wien, Austria, 1992; Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Canada, 1994 (travelled to Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas); Daimaru Museum of Art, Tokyo, 1995 (travelled to Genichiro-Inkuma Museum of Contemporary Art, Kagawa, and Kintetsu Museum of Art, Osaka); Saatchi Gallery, London, 1997; Museum of Art, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, 1998 (travelled to Flint Institute of Arts, Michigan; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; and Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, Memphis); and Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt, 2001 (travelled to Padiglione d'Arte Contemporanea, Milan; Kunsthal Rotterdam, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, and Kunsthaus Zürich). Image Credit: Duane Hanson Self Portrait with Model, 1979 ©The Estate of Duane Hanson Courtesy the Estate of Duane Hanson and Gagosian Gallery Photography by Alan Ginsburg, Hamburg Duane Hanson 2 June – 13 September 2015, Serpentine Sackler Gallery List of Works Trash 1967 Polyester resin and fibreglass, mixed media, with accessories The Estate of Duane Hanson Photograph: Rob McKeever Man with Hand Cart 1975 Polyester resin and fibreglass, polychromed in oil, mixed media, with accessories The Estate of Duane Hanson Photograph: Rob McKeever Children Playing Game 1979 Polyvinyl, polychromed in oil, mixed media, with accessories The Estate of Duane Hanson Photograph: Rob McKeever Self-Portrait with Model 1979 Polyvinyl, polychromed in oil, mixed media, with accessories The Estate of Duane Hanson Cowboy 1984/1995 Autobody filler, polychromed in oil, mixed media, with accessories The Estate of Duane Hanson Photograph: Rob McKeever House Painter I 1984/1988 Autobody filler, polychromed in oil, mixed media, with accessories The Estate of Duane Hanson Queenie II 1988 Autobody filler, polychromed in oil, mixed media, with accessories The Estate of Duane Hanson Lunchbreak 1989 Polyvinyl, polychromed in oil, mixed media, with accessories The Estate of Duane Hanson Flea Market Lady 1990/1994* Edition 4/4 (unique editions) Bronze, polychromed in oil, mixed media, with accessories Collection of Gilbert Costes Photo: Florian Kleinefenn Image courtesy of Galerie Perrotin Homeless Person 1991* Autobody filler, polychromed in oil, mixed media, with accessories Collection Hannes von Goesseln at Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg Photograph: Galerie Neuendorf Old Couple on a Bench 1994 Edition 1/2 (unique editions) Bronze, polychromed in oil, mixed media, with accessories The Estate of Duane Hanson Baby in Stroller 1995 Polyvinyl, polychromed in oil, mixed media, with accessories The Estate of Duane Hanson Photograph: Rob McKeever Man on Mower 1995 Edition 1/3 (unique editions) Bronze, polychromed in oil, with lawn mower The Estate of Duane Hanson Directors’ Foreword In the turmoil of everyday life, we too seldom become aware of one another. In the quiet moments in which you observe my work, maybe you will recognize the universality of all people. Duane Hanson1 Over the course of his lifetime, Duane Hanson (1925–1996) created extraordinary figures: life-size sculptures of human beings, described in minute detail, dressed in real clothes and often placed alongside real objects. For the most part they were cast from models, however these figures are not portraits of individuals. Hanson sought to produce characters representative of people from all walks of life, imbued with a sense of internal narrative that encourages a level of observation bordering on voyeurism. The experience of viewing these works is one of both pleasure and discomfort. This exhibition is a survey of some of the key works produced by Hanson throughout his career. In his first works from the 1960s, Hanson’s sensitivity to the political and social upheavals unfolding in the 7 United States found direct expression in sculptures that brought the outside world into the art gallery. The earliest piece in the exhibition at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery is the shocking Trash (1967), which includes a dead newborn baby in a rubbish bin. During the 1970s Hanson turned from overt violence to the isolation and fatigue suffered by figures that were more familiar and, therefore, more overlooked. The Man with Hand Cart (1975) lost in thought; the workers relaxing in Lunchbreak (1989); and the despairing Homeless Person (1991) are arresting firstly because of their ordinariness and because we are able to observe them without interrupting their reverie. Painstakingly produced but apparently captured in a single moment, the humanity of Hanson’s sculptures surprises and disarms us at every turn. We are constantly forced to reassess what is real and what is not, and we are left with a new awareness of ourselves, as well as a renewed curiosity in and sympathy for our fellow humans. Hanson’s steadfast adherence to the realistic production of the human body in a period when the notion of figurative art was generally viewed with scepticism has earned him great respect, and his influence on younger generations of artists should not be underestimated. Contemporary explorations into ways of addressing the human figure take up Hanson’s prediction that ‘the art of the future will reflect a [greater] reliance on technology’,2 with artists using new materials and new processes such as High-Definition digital avatars and 3D printing. This exhibition could not have been possible without the assistance of a number of individuals. We are indebted to the artist’s wife Wesla Hanson, his children Maja Hanson Currier and Duane Hanson Jr., and daughter-in-law Shannon Hanson at The Estate of Duane Hanson for their enthusiasm for this exhibition and for working with us on so many important aspects of its presentation. Their generosity in donating a series of unique Polaroids to become a Limited Edition is remarkable and we cannot thank them enough. The Lars Windhorst Foundation has generously supported the summer season across the Serpentine Galleries for which we are extremely thankful. It is the second year that the Foundation’s substantial donation has enabled us to present an historical exhibition in dialogue with a young British artist. We are extremely grateful for the Foundation’s ongoing commitment. We express our gratitude to Phillips for their invaluable contribution to this exhibition. We would also like to thank Gagosian Gallery for their support and, in particular, Andy Avini and Martha Blakey for their hard work and assistance. In addition we thank the Duane Hanson Exhibition Circle and the Americas Foundation of the Serpentine Galleries for their support, which has been crucial to the realisation of this project. Our thanks are extended to the generous lenders to the exhibition: Gilbert Costes, The Estate of Duane Hanson and Gagosian Gallery, and Hannes von Goesseln whom we also thank for his wonderful insight and advice. The public funding that the Serpentine receives through Arts Council England provides an important contribution towards all of the Galleries’ work and we remain very appreciative of their continued commitment. The Council of the Serpentine is an extraordinary group that provides essential ongoing support to the Galleries that ensures the continued success of the institution. The Learning Council, Patrons, Future Contemporaries and Benefactors are also key supporters of the Serpentine’s programme and we thank them. Our sincere thanks go to Ruba Katrib, whose insightful essay in this publication provides important links between Hanson’s practice and its relationship to ongoing concerns about the presence of the body in contemporary art. Thanks also go to Douglas Coupland, who has written a personal response to Hanson’s work that is a testament to its enduring legacy. Julia Peyton-Jones Director, Serpentine Galleries and Co-Director, Exhibitions and Programmes Hans Ulrich Obrist Co-Director, Exhibitions and Programmes and Director of International Projects This book has been designed by Brendan Dugan and we are indebted to him and to his colleagues for helping to produce such a beautiful and unique publication. Finally, we would like to thank the Serpentine team: Jochen Volz, 8 Head of Programmes; Rebecca Lewin, Exhibitions Curator; Melissa Blanchflower, Assistant Curator; Mike Gaughan, Gallery Manager and Joel Bunn, Installation and Production Manager have all worked closely with the wider Serpentine Galleries staff to realise this exhibition and we are most grateful for their hard work and dedication. 9 1. Unpublished. Written in Davie, Florida, 1993 2. Unpublished. Written in Davie, Florida, c.1982 Surface Identity by Ruba Katrib Duane Hanson made people. He fixated on the mundane individuality of janitors and shoppers, tourists and the elderly, primarily members of the working class. The skin of his figures, largely made out of polyester resin, and their real clothes, gives them a veracity that permits us to examine intimately those whom we might otherwise only furtively watch; Hanson indulges our perverse pleasure in being able to look at the overweight woman with the stroller without worrying that she will return our impolite gaze. We might even experience the thrill of thinking the figures are alive, and then realising that they are art. For some, there is a confrontation with those whom they might not usually notice. Perhaps for others, the voyeuristic thrill is translated into dull dis­comfort: ‘I must now consider this person.’ In either case, the average American is isolated and memorialised in Hanson’s work. The surfaces of human bodies have been etched into marble and cast in bronze over centuries of sculpture production. These traditional artworks, while achieving a close resemblance in terms of form, have also maintained a distancing effect; 127 whether figurative or abstract, a marble or bronze statue isn’t meant to fool. However, in the last decades, bodies have been rendered with materials more closely resembling flesh. Plastics, silicones and other synthetic substances have contributed to new material relationships. Instead of focusing on the form of the body and on its shape as indicator of subject, there is now an interest in its material composition. In Hanson’s work, the polyester resin he used could convincingly mimic the translucence of real skin. Writing in the 1950s, Roland Barthes addressed the ubiquity of new synthetic materials and their impact on notions of humanness: ‘The hierarchy of substances is abolished: a single one replaces them all: the whole world can be plasticised, and even life itself since, we are told, they are beginning to make plastic aortas.’1 Concurrently, Marcel Duchamp’s wedding gift for his new bride Teeny Matisse, Coin de chasteté (Wedge of Chastity) (1954) is a bronze block jammed into a pink chunk of dental plastic to conceal a delicately crafted vagina. This work was part of a group of three erotic sculptures, including Feuille de vigne femelle (Female Fig Leaf) (1950) and Objet-dard (Dart Object) (1951).2 These are mostly bronze casts, but with Wedge of Chastity, the introduction of the dental plastic as raw material to represent flesh marks a significant precursor to the use of plastics and synthetic compounds to represent organic forms in cotemporary art. The synthetic substance used to take the impression of the mouth in a dentist’s office easily and humorously transforms into a fleshy vagina. Using the pink plastic as shorthand for skin, Duchamp anticipated the use of new materials as signifiers for the texture of the body, rather than relying on its form. In Hanson’s exhibition catalogues, including this one, there are often images documenting the making of his sculptures, revealing the intensive casting process, the attention paid to the painstaking details, the loving touches made to complete his figures. Through these images we see that they not only undergo demanding moulding and casting processes, but that they also go through wardrobe, hair and makeup with the addition of eyelashes, real clothes, wigs and props. For Hanson, working in the 1970s and 1980s, identity is expressed through skin colour and clothing, products and tools; the clothes, food and objects with which his figures interact emphasises their dependency on these articles to construct their individuality. Using the garments of the time, he placed his sculptures in a cultural moment. A prominent section of this publication also shows previously unprinted documentation of viewers coming face to face with the sculptures – encounters full of surprise, scrutiny and interest. That his figures provoke this wonder touches on an essential dynamic of Hanson’s work: his sculptures are so straightforward that they are disarming; we want to understand how they came into being and how they operate in the world. The attraction of Hanson’s figures lies in the fact that they are familiar and fully realised, yet lifeless. Building up his sculptures piece by piece until they became legible as contemporary subjects, he removed the distancing effects found in most sculptural representations of the human body. In this sense, his works follow a different trajectory from that of the monument and portraiture. They are too close to real, eliminating the space required for interpretation. By making these sculptures, which speak in the 128 language of monuments and statues, so accurate, with their bad hair and flawed skin, that they can momentarily trick the viewer into thinking they are real, Hanson creates a distinct break from historic, idealised representations. This marks a transition between the illusion of the body as one single chunk, as in historical sculpture, into the increasingly fragmented body of much recent contemporary art. He also touches on the identity construction that would come to define the works of the 1990s, and which in a sense re-aggrandise their subjects as representative individuals. Most of the subjects depicted in Hanson’s sculptures are everyday people, workers and consumers. Intent on articulating a notion of averageness and an awareness of those people who comprise the margins of society, Hanson emphasises that these are not heroic figures. They aren’t special. Their individuality isn’t remarkable – they are meant to live in the crowd – an element underscored when they are seen in a busy gallery. They can be disregarded, perhaps even discarded. This is particularly true of an explicitly disturbing early sculpture 129 included in the exhibition – a suffocated foetus in a trashcan – which colours our view of Hanson’s other works depicting destitute individuals and violent scenes. A figure among other objects – an old egg carton and umbrella – the body in this work takes on the same status as the debris with which it has been thrown. Hanson’s figures are immediately legible in terms of surface, straightforward proclamations of character: I am a shopper, I am a janitor, I am a tourist. Their identity can be taken for granted: they fulfil a simple role, satisfying expectations through their veracity. Surface markers are central: it’s all happening on the exterior. We can only imagine their interior states, which are locked away, as they are for their counterparts on the street. The superficiality of the works uncovers attitudes about identity at the time that they were made, and reveals much about how identity is constructed now. In the 1980s and 90s, artists such as Charles Ray and Robert Gober, who also mimic flesh in their sculptures, truncated and rescaled the figure to create uncanny effects. The body was seen in pieces, or distorted Hanson’s investigation of the complete, realistic body has not reappeared as a subject in contemporary art, although his fixation on identity through material construction has become a central aspect of several artists’ works. Today, the representation of the body has become even more abstracted. With new synthetics and production processes, rendering the body has changed. Skin has become malleable material. And identity construction, while still connected to superficial markers such as ethnicity and clothing, has become more fluid. The intimacy shared with synthetic substances has now become an acknowledged aspect of identity construction, one necessarily investigated by artists who address bodily forms. Current artists have represented body politics through a deeper understanding of biology, technology and the porousness of the body as comprised through effects and substances, many of which are invisible. Articulating identity through the material of skin, for example, Pamela Rosenkranz has turned flesh into a substance that is no longer tied to the armature of the skeleton. Anicka Yi identifies individuals through bacteria samples. Frank Benson depicts the human form as anatomically correct and hyper-real, but charges it with contemporary identity expressions. Benson’s sculptures are more in line with Hanson’s, in that they are technically sophisticated renderings of actual bodies. Juliana (2015) is a 3D-printed nude figure of transsexual artist Juliana Huxtable reclining on a plinth. Though the sculpture is technically exact, the skin is painted with a bluish green iridescent paint, almost resembling the surface of a car. Thus Benson has transformed the portrait into commodity, despite its likeness. Rosenkranz pours Dragon Skin, a silicone rubber used to mimic skin in special effects and prosthesis, into water bottles and sneakers. Taking a substance that can so closely resemble skin – translucent and dyed a range of tones – and turning it into product, Rosenkranz also addresses the merging of identity and body with commodity. She has stated her interest in how synthetic substances such as hormones and plastics leeching into our water supplies impact the body, contributing to our sense of self.3 Our clothing choices might be affected less by how we see ourselves in the world, and more by the chemicals we regularly and unknowingly 130 ingest. Anicka Yi has created a portrait of 100 women by gathering skin swabs. Combining them into a single large-scale Petri dish, Yi has formed a sculptural group portrait using human bacteria. The identity of the body is provisional and transformable, impacted by, as well as impacting on, the material world it inhabits. Identity is increasingly linked, not only to background, ethnicity, and gender, but also to chemicals and clothes. It is now increasingly malleable, as is the representation of the human form. In Hanson’s sculptures, the body is seen not as a commodity itself, but in relationship with commodities. It is viewed as separate from the accessories around it, buying, wearing and using these products, not yet fully integrating them. The consumer, like the overweight woman in Supermarket Shopper (1970), is still seen as independent from the goods she acquires. She is still behind the wheel, seemingly in control of the things she is selecting, in contrast with today’s articulations of the body, which bear witness to the merging of corpus, identity and product. In Hanson’s works, there remains a gap between the body and things. 131 1. Roland Barthes, Mythologies, (New York: Hill and Wang, 2012) p.195. 2. Helen Molesworth (ed.), Part Object Part Sculpture, Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, 2005, p.29. 3. ‘I am concerned with exploring how scientific findings change popular conceptions of what it means to be human, and that can be quite confrontational. For example, it’s interesting how advances in neuroscience challenge our understanding of identity. Through new scientific research into the evolutionary history of the brain, we can understand the self not as a fixed entity but as an ever-changing process.’ Pamela Rosenkranz in Aofie Rosenmeyer, ‘In the Studio: Pamela Rosenkranz’, Art in America (January 2015), p.79; online at www.artinamericamagazine.com/news-features/magazine/inthe-studio-pamela-rosenkranz. Duane Hanson: Realness, not Realism by Douglas Coupland There are some creators who died a bit too early, and who never lived to see their work get the full attention it deserved. Van Gogh comes to mind, as does Scott Fitzgerald, as does Duane Hanson. Hanson created hyperrealist figurative work at a moment in art history when to be sculpturally figurative was academically anathema. His work was enormously popular with the public and this also made him critically suspect, a fact of which he was well aware. To be underrated because of transient political vogues left Hanson without a full sense of artistic community, and this feeling of isolation is in evidence in his work, particularly in the solo figures created in the last two decades of his life. Their loneliness is almost achingly beautiful, and is reminiscent of a fellow American unique, Edward Hopper. I remember for the first time seeing Hanson’s work – Tourists (1970) – in my early twenties, and I remember my realist wow moment – a moment that most people also experience upon encountering his work, and I very much remember wondering how does he do it? Technical prowess is something I always appreciate in artwork, but some people read 133 prowess as entertainment. I never got that from his pieces. Hanson created the realism that he did because there was no other way for him to convey the relationship he saw between individuals and the societies they inhabit. His realism wasn’t Madame Tussauds, and it wasn’t mannequins in the store windows at Macy’s . . . so then what was it? It was only later in life that I realised Hanson was going for realness, a term used by drag queens in competitions when portraying archetypes: rich white women dressed for lunch; high-school football players getting their photos taken for the yearbook. The word ‘archetype’ is important here because Hanson was often dismissed as someone who worked in stereotypes – ontologically similar but wrong. Archetypes depict universal modes of being that reconfigure themselves over and over again across time, geography and cuture. Stereotypes are exaggerated characteristics temporarily tainted with conscious or subconscious contempt. Right now, the 1970s are almost half a century away from us and we have a bit of distance from that era. Hanson’s largely middle- and lowermiddle-class figures do convey the late twentieth-century nothingness beneath the sheen of consumer culture, but more importantly, as the middle-class unravels, as it’s doing now, we’re learning that the shopping carts aren’t as full as they once were. We’re learning that to be a cartoon-like American tourist abroad is probably a bad idea that will most likely invite bad experiences. We’re also realising that not far down the road, many museum-goers will share the same crappy jobs or no work at all, just like Hanson’s drifters. It’s always fascinating to watch the general public interact with Hanson’s work, and to see the inevitable wow moment. It seems tailor-made for our current era – in fact, could there be any work out there more selfie-friendly than Hanson’s? Technology has inverted some of the rules of the institutional artistic experience. What was once forbidden in the museum (the photo) is now encouraged. The eyeballs of Hanson’s figures no longer look out into space, but instead at the viewer’s camera aperture along with the viewer. What was once a power-imbalanced relationship, the institution and the viewer, instead becomes intimate, curious, democratic and highly engaged. A new museum archive category seems to be emerging – a continuum of ‘selfieness’. At one end of the selfie spectrum is, say, Donald Judd’s work. It’s hard to imagine taking a selfie with one of his wall pieces – although his long-term installations in Marfa, Texas, are now an off-grid tourist destination for art fair aficionados, and a surprising number of people make the Spiral Jetty pilgrimage to Robert Smithson’s land art in remotest Utah, so you never know. And at the other end of the selfie continuum we have Hanson and, say, Jeff Koons. Selfieness is no indication of a work’s depth or anything else except, well, its selfieness. But whatever selfieness is, it’s possibly what institutions are looking for to help them navigate through the next twenty years. So maybe it’s not so odd a category after all. But aside from the typical museumgoer, there are members of the art world, both older and younger, who arrive at Hanson’s work with a different set of experience filters. Younger people never saw Hanson’s real-life human subjects back in the day, and view Hanson’s work as historical: Can you believe people really dressed like that and did all that crazy stuff ? And then there 134 are older art-world habitués who probably remember the unspoken ideological fatwa on Hanson and who, maybe, if they’re honest, helped perpetuate it; and now these people are old and falling apart, and there is Hanson’s work, eternal and as fresh as ever. Hanson is now seen as the grandfather of a large and thriving genre of visual art dealing with hyperreal figuration, and young people find it impossible to believe that someone whose work was so intense and so true could ever have been perceived as an outsider. Time always tells. Hanson’s work is now only viewed in museums, and watching museumgoers interacting with his forms is just as much a part of experiencing his work as admiring it on its own. It’s very different from seeing mannequins at the mall or dioramas in anthropology museums. Hanson’s pieces are right there, coequal with you. In some ways they feel more authentic than you: they come from an era where authenticity was the default mode of being, an era when reality reigned, and where a word like ‘realness’ was still only something in an artist’s and a drag queen’s magic bag of tricks. 135