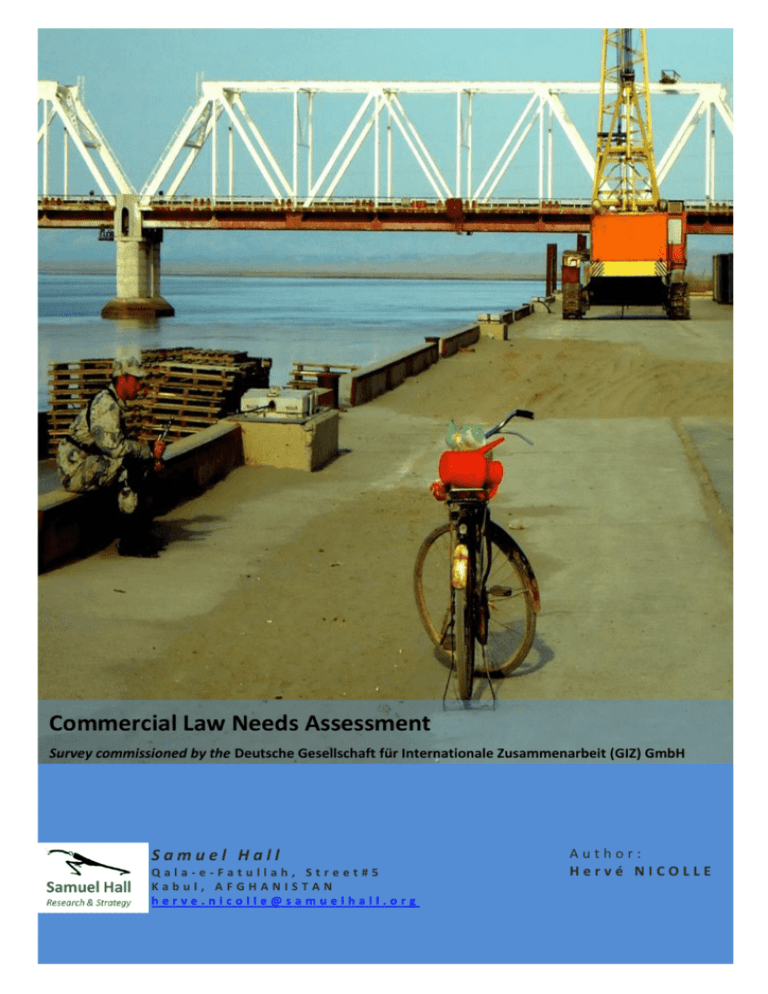

Commercial Law Needs Assessment

advertisement