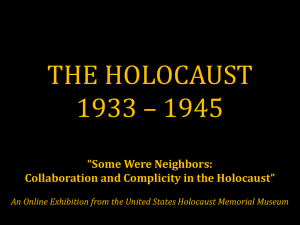

Aftermath - The Holocaust and Human Rights Education Center

advertisement

Lesson 7 Aftermath Introduction CONTENTS Lesson Overview . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 275 Quotation Bearing Witness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 277 Document 1A Population Table . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 278 Document 1B Map: Survivors of the Holocaust, 1945 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 279 Document 2A Reading: Night by Elie Wiesel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 280 Document 2B Reading: “My War Began in 1945” by Deborah Dwork . . 282 Document 3A Chronology of Events . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 283 Document 3B Reading: “What Will Become of Us?” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 285 Document 3C Photo: Exodus Protest . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 288 Document 4A Reading: War Crimes Trials. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 289 Document 4B Reading: The Nazi Hunter . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 290 Document 4C Reading: The Most-Wanted Nazi . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 291 Document 5 Poem: “The Hangman” by Maurice Ogden . . . . . . . . . . . . . 292 Document 6 Reading: Universal Declaration of Human Rights . . . . . . . . 294 Document 7 Cartoon: “Ethnic Cleansing Center” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 295 Document 8 Poem: “Riddle” by William Heyen . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 296 Document 9 The Universe of Obligation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 298 The HHREC gratefully acknowledges the funders who supported our curriculum project: • Office of State Senator Vincent Leibell/New York State Department of Education • Fuji Photo Film USA 274 Aftermath KEY VOCABULARY Adolf Eichmann displaced person (DP) DP camp LESSON OVERVIEW In this lesson students will examine the difficulties faced by the survivors of the Holocaust. They will also examine the way in which the perpetrators were handled after the war. Exodus International Military Tribunal partition Simon Wiesenthal survivor Universal Declaration of Human Rights INSTRUCTIONAL PLAN AND ACTIVITIES Activity 1 • Distribute Documents 1A to 3C to students. Discuss the difficulties the survivors faced psychologically, politically, economically, and socially. war crimes trials OBJECTIVES • Students will raise and consider key questions regarding the Holocaust. • Students will realize that man’s inhumanity to man can surface in a variety of historical circumstances. • Students will understand the dangers of blind obedience to authority. • Students will carry the message so that it cannot happen again. ESSENTIAL QUESTION How were those involved in the Holocaust affected in the years following the war? Aftermath Activity 2 • Ask students to read Documents 4A to 4C. Discuss whether high-ranking Nazi officials should continue to be pursued and prosecuted. Has justice been served by the punishment of these officials? Activity 3 • What do documents 5 to 7 suggest that we have learned in the years since the Holocaust? Activity 4 • Distribute the graphic organizer “Your Universe of Obligation.” Document 9. Remind the students that they completed this activity at the beginning of the unit. Ask students why they think it is being repeated here. Ask students to complete the organizer. Ask students how this differs from the one they completed at the beginning of the unit. 275 RESOURCES 1A Population Table 1B Map: Survivors of the Holocaust, 1945 2A Reading: Night by Elie Wiesel 2B Reading: “My War Began in 1945” by Deborah Dwork Concluding Question Why, after all this, have the words “never again” gone unheeded? Contemporary Connection and Homework Read “Something in Common: Horror.” Answer the questions in writing. 3A Chronology of Events 3B Reading: “What Will Become of Us?” 3C Photo: Exodus Protest 4A Reading: War Crimes Trials 4B Reading: The Nazi Hunter 4C Reading: The Most-Wanted Nazi 5 Poem: “The Hangman” by Maurice Ogden 6 Reading: Universal Declaration of Human Rights 7 Cartoon: “Ethnic Cleansing Center” 8 Poem: “Riddle” by William Heyen 9 The Universe of Obligation 276 Aftermath QUOTATIONS by Elie Wiesel “For the dead and the living we must bear witness. For not only are we responsible for the memories of the dead, we are also responsible for what we do with those memories.” Elie Wiesel Wiesel, Elie. Night. (New York, Bantam, 1982). “History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived, but if faced with courage, need not be lived again.” Maya Angelou http://www.quotationspace.com/quote/31974.html Aftermath 277 DOCUMENT 1A Population Table This table shows the number of Jews that were killed by Hitler’s government. Use the information to answer the questions that follow. From The War Against the Jews by Lucy S. Dawdowicz, 1962. Reprinted by permission. QUESTIONS 1. Examine the population table and comment on the following a. The number and percentage of Jews killed in Poland vs. Germany. b. The number and percentage of Jews killed in France, Bulgaria, Italy, and Luxembourg. 2. Now use the table again to answer these questions. a. Why were a high percentage of Jews killed in some countries while a low percentage were killed in other countries? b. Why must tables be examined and used very carefully? 278 Aftermath DOCUMENT 1B Map: Survivors of the Holocaust, 1945 Martin Gilbert, Atlas of the Holocaust (New York: William Morrow, 1983), 242. QUESTIONS Consider the information on Document 1A, which shows the number and percentage of Jews killed. Why must one be careful about drawing conclusions about Document 1B. Aftermath 279 DOCUMENT 2A Night by Elie Wiesel Liberation I had to stay at Buchenwald until April eleventh. I have nothing to say of my life during this period. It no longer mattered. After my father’s death, nothing could touch me any more. I was transferred to the children’s block, where there was six hundred of us. The front was drawing nearer. I spent my days in a state of total idleness. And I had but one desire—to eat. I no longer thought of my father or of my mother. From time to time I would dream of a drop of soup, of an extra ration of soup… On April fifth, the wheel of history turned. It was late in the afternoon. We were standing in the block, waiting for an SS man to come and count us. He was late in coming. Such a delay was unknown till then in the history of Buchenwald. Something must have happened. Two hours later the loudspeakers sent out an order from the head of the camp: all the Jews must come to the assembly place. This was the end! Hitler was going to keep his promise. The children in our block went toward the place. There was nothing else we could do. Gustav, the head of the block, made this clear to us with his truncheon. But on the way we met some prisoners who whispered to us: “Go back to your block, and don’t move.” We went back to our block. We learned on the way that the camp resistance organization had decided not to abandon the Jews and was going to prevent their being liquidated. As it was late and there was great upheaval— innumerable Jews had passed themselves off as 280 non-Jews—the head of the camp decided that a general roll call would take place the following day. Everybody would have to be present. The roll call took place. The head of the camp announced that Buchenwald was to be liquidated. Ten blocks of deportees would be evacuated each day. From this moment, there would be no further distribution of bread and soup. And the evacuation began. Every day, several thousand prisoners went through the camp gate and never came back. On April tenth, there were still about twenty thousand of us in the camp, including several hundred children. They decided to evacuate us all at once, right on until the evening. Afterward, they were going to blow up the camp. So we were massed in the huge assembly square, in rows of five, waiting to see the gate open. Suddenly, the sirens began to wail. An alert! We went back to the blocks. It was too late to evacuate us that evening. The evacuation was postponed again to the following day. We were tormented with hunger. We had eaten nothing for six days, except a bit of grass or some potato peelings found near the kitchens. At ten o’clock in the morning the SS scattered through the camp, moving the last victims toward the assembly place. Then the resistance movement decided to act. Armed men suddenly rose up everywhere. Bursts of firing. Grenades exploding. We children stayed flat on the ground in the block. The battle did not last long. Toward noon everything was quiet again. The SS had fled and the resistance had taken charge of the running of the camp. Aftermath DOCUMENT 2A (Continued) Night by Elie Wiesel At about six o’clock in the evening, the first American tank stood at the gates of Buchenwald. Our first act as free men was to throw ourselves onto the provisions. We thought only of that. Not of revenge, not of our families. Nothing but bread. And even when we were no longer hungry, there was still no one who thought of revenge. On the following day, some of the young men went to Weiman to get some potatoes and clothes—and to sleep with girls. But of revenge, not a sign. Three days after the liberation of Buchenwald I became very ill with food poisoning. I was transferred to the hospital and spent two weeks between life and death. One day I was able to get up, after gathering all my strength. I wanted to see myself in the mirror hanging on the opposite wall. I had not seen myself since the ghetto. From the depths of the mirror, a corpse gazed back at me. The look in his eyes, as they stared into mine, has never left me. Elie Wiesel, Night. New York: Bantam, 1982. 117-119 QUESTIONS 1. What events are described in this passage? 2. What was Elie Wiesel thinking at this time? 3. Interpret what Wiesel sees in the mirror. Aftermath 281 DOCUMENT 2B “My War Began in 1945” by Deborah Dwork During the war, I, Maurits Cohen was a child and I was engaged with everyday living. The very impact of the consequences of the war I experienced after the war ended. My war began in 1945, and not in 1940. When I learned that my father and mother would not come back, and my brothers, then the war started. It took me years to get used to the idea, to find my own place, an only child, of course. We had had a very big family, so as a child I had to carry the whole weight of survival. Deborah Dwork, “My War Began in 1945,” in Images of the Holocaust: A Literature Anthology, ed. Jean E. Brown, Elaine C. Stephens and Janet E. Rubin (Lincolnwood, IL: NTC, 1997), 425. QUESTIONS 1. As a Jewish child, how could he have been “engaged with everyday living” during the war? 2. Why did he say that his war began in 1945? 282 Aftermath DOCUMENT 3A Chronology of Events 1944 July 23 Majdanek near Lublin, Poland, becomes the first Nazi death camp to be liberated. 1945 January–May Most Nazi death and concentration camps are liberated. May 7 Unconditional surrender of Germany ends World War II in Europe. August U.S. General Patton grudgingly accompanies General Eisenhower on a tour of the Feldafing Displaced Persons Camp in Germany. In an August 31 letter to his wife, Patton comments that “Actually the Germans are the only decent people left in Europe.” October David Ben-Gurion visits the displaced persons camps in Europe and tells survivors that all who want to go to Palestine will be taken there as soon as possible. December 22 President Truman’s order grants special permission to displaced persons who want to enter the United States; some 22,950 arrive. 1946 March 19 July 4 July 22 Chaim Hirschmann, one of two survivors of the Belzec death camps, is killed upon his return to Lublin, Poland. Pogrom in Kielce, Poland, against 150 returning Jewish survivors leaves fortytwo dead and fifty wounded. Agents of the radical Jewish group Irgun blow up the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, killing ninety-one British, Arabs, and Jews. 1947 One million displaced persons remain in the camps of Europe. July 18 Jewish refugee ship Exodus is rammed by British destroyers off the coast of Haifa, Palestine. Passengers and crew are arrested and returned to Europe. November 29 United Nations General Assembly adopts a resolution for partitioning Palestine into two states, an Arab and a Jewish. The partition becomes effective in May 1948, when the British mandate in Palestine expires. Aftermath 283 DOCUMENT 3A (Continued) Chronology of Events 1948 April 9 May 14 Jewish extremist groups massacre the residents in the Arab village of Deir Yassin. British mandate to rule Palestine expires. David Ben-Gurion declares birth of the Jewish State of Israel. Fighting between the Arabs and Jews—the Israeli War of Independence—begins. May 28 Arabs take over the Old City of Jerusalem in the Israeli War of Independence. June 11 First UN-supervised truce in the War of Independence begins. It is broken on July 9 in a fight for the Negev. Second truce takes effect July 18. June 25 U.S. immigration law allows 200,000 immigrants to enter the United States over the next two years, but with stiff restrictions. Ultimately the law is modified to be less discriminatory against Jews. June 26 Allied pilots begin largest airlift in world history, flying tons of food, fuel, and supplies into communist-controlled Berlin to relieve the Soviet blockade around the city. September 17 Count Folke Bernadotte, UN mediator in the Arab-Israeli war, and his assistant, are assassinated by a Jewish terrorist group. October 14 Third round of the Israeli War of Independence begins with Egyptians fighting the Israelis in the Negev. 1949 January 12 February August 14 Peace talks begin between Arabs and Israelis and individual Arab countries. David Ben-Gurion elected the first prime minister of Israel. Body of Theodor Herzl, father of Zionism, arrives in Israel and is buried on a hill above Jerusalem. 1950 Law of Return is passed by the Knesset, the Israeli Parliament, granting every Jew worldwide the right to settle permanently in Israel. December 17 Central Committee of the Jewish Displaced Persons is disbanded. All refugees who wanted to immigrate to Israel have arrived. 1950 Law passed by the Knesset grants citizenship to all Jewish immigrants. QUESTION What difficulties did surviving Jews face after World War II? 284 Aftermath DOCUMENT 3B “What Will Become of Us?” Hitler’s goal in the Final Solution was to see that not a single Jew survived. He came frighteningly close to realizing his goal. Approximately 6 million of the 11 million Jews living in Europe before World War II were dead by the war’s end. The Jews who somehow managed to survive the war, whether in concentration camps, in hiding, or in exile in the Soviet Union and other countries, now faced a new nightmare. They had to deal with the loss of their friends, families, homes—sometimes entire communities. They were alive—but most were alone, with no place to go. Many were plagued by guilt, feeling that they did not deserve to live when so many others had been killed. Among those murdered in the Holocaust were 11⁄ 2 million children. There were also many war orphans—thousands of children who survived, but without their parents. In many parts of war-torn Europe, orphanages were set up to care for these youngsters. “Beaten Both Spiritually and Physically” To help survivors, the Allies set up Displaced Persons (DP) camps, where people could get food, medical care, a place to sleep, and—ideally—news of loved ones. But, often, conditions were nearly as bad in the DP camps as they had been in the concentration camps. Wrote the director of one such DP camp in Germany: The camp is filthy beyond description. Sanitation is…unknown… With few exceptions the people…appear demoralized beyond hope of rehabilitation. They appear to be beaten both spiritually and physically. Aftermath Unlike the other Allies, the Soviets, who had driven dozen of Nazis out of Poland, did not establish Displaced Persons camps. Instead, they maintained that there was no refugee problem. As a result, nearly 1 million people liberated from the Nazi camps in Poland were left completely on their own to find food and shelter. Weak, downtrodden, and confused, many simply wandered before finally succumbing to death. Europe in Tatters Nearly all of Europe had been devastated by the six long years of war. Millions of Europeans desperately needed food and fuel. Medical supplies, too, were scarce. Disease was rampant across the continent. There were nearly 10 million Displaced Persons when the war ended. No one in the Allied command had ever anticipated there would be so many DPs in need of help. The Allies faced the formidable problem of not only feeding and clothing these people but also providing shelter for them. Because of the enormity of the DP problem, Holocaust survivors were not immediately offered special care. In the meantime, malnutrition and infectious diseases continued to take a deadly toll on camp survivors. Conditions for the prisoners at many camps had deteriorated dramatically near the end of the war. Of the prisoners liberated at Bergen-Belsen in April 1945, tens of thousands had died by June. In addition to the acute physical needs of survivors, there were also serious psychological needs that required attention. After liberation, some survivors were confined within the same fences that had previously been patrolled by 285 DOCUMENT 3B (Continued) “What Will Become of Us?” Nazis. With clothes in short supply, many still wore their concentration camp-issue striped uniforms; others could find no clothing other than German SS uniforms—the very items that had once clothed their oppressors. In many cases, Jewish survivors were confined in the same quarters with former camp guards and Nazi collaborators. “The Civilized World Owes It…” In 1945, the U.S. State Department, under pressure from the American public, sent Earl Harrison, a former U.S. immigration commissioner, to Europe. It was his responsibility to report firsthand on the conditions in the refugee camps in the American sector of occupied Germany. Harrison confirmed what had already been told in various newspaper accounts. He wrote in his report to the U.S. President Harry Truman: “…they are in need of attention and help. Up to this point, they have been ‘liberated’ more in a military sense than actually.” Harrison delivered harsh criticism, writing, “As matters now stand, we appear to be treating the Jews as the Nazis treated them, except that we do not exterminate them.” He then summarized various avenues that he felt would improve the situation: In conclusion, I wish to repeat that the main solution, in many ways the only real solution, of the problem lies in the quick evacuation of all nonrepatriable [stateless] Jews in Germany and Austria, who wish it, to Palestine. In order to be effective, this plan must not be long delayed. The civilized world owes it to this handful of survivors. 286 Upon receiving the report, Truman immediately issued a series of orders to address the situation. In Europe, General Eisenhower himself oversaw their implementation. To begin, U.S. military officials relieved Germans of their positions administering certain camps. They also relieved the overcrowding, improved unsanitary conditions, and increased daily food rations. A tracing bureau was created to assist survivors in locating family members who might have survived, but this was largely ineffective. By the fall of 1945, thanks largely to Harrison’s report and Truman’s response, life for Jewish survivors in the DP camps had improved somewhat. Plans were also under way to establish camps specifically for Jewish survivors. But still no progress had been made in finding the Jews a permanent home. By September 1945, the Allies had returned approximately 7 million DPs to their homelands. Just under 2 million remained in Germany. Hatred at Home Anti-Semitism had not ended in Europe simply because the armies of Nazi Germany had been defeated. Numerous pogroms—organized mob violence—against Jews still took place across Poland between September and December 1945. In the Polish town of Piekuszow, a mob pulled a 70-year-old Jewish woman from a train and stoned her to death. Six other Jews also lost their lives there. Several hundred Polish Jews who had managed to live through years of the Holocaust were murdered in similar incidents immediately following the war. But Jews continued to return to their homes in Poland. Where else could they go? Aftermath DOCUMENT 3B (Continued) “What Will Become of Us?” An estimated 175,000 Jews—a small fraction of the more than 3.5 million Jews who had lived in Poland before the war—had taken refuge in the Soviet Union during the war. Early in 1946, they returned home. In the Polish town of Kielce, 150 Jews returned with the hope of reestablishing their community. Within months, however, it became clear that coming home would not be easy. In July, a mob of townspeople attacked the returned Jews, killing 41, and wounding 50 more. When word of this attack spread, Jews once again began fleeing Poland. More than 100,000 sought refuge in the British and American sectors of occupied Germany. By 1947, the number of Jews in DP camps was well over 200,000. To Where? In his report to the State Department, Harrison had urged the United States to help get the Jews out of Germany. But neither the British nor the Americans were willing to raise their immigration quotas to allow more Jewish refugees into their countries. President Truman urged the British government to allow Jewish DPs into Palestine, a land in the Middle East under British control. But the situation there was complex. The British, fearful of repercussions from Palestinian Arabs, were restricting Jewish immigration to Palestine. As late as 1947, two years after the end of the war, the Jewish refugee problem remained unsolved. More than 200,000 European Jews were still in need of a home—or a homeland. At that point Jewish refugees comprised nearly onequarter of the remaining DP population. Many dreamed of going to Palestine. Others desperately wanted to begin a new life in the United States. Most would have been happy just to leave Europe forever. The situation remained unresolved into 1948. Eleanor Ayer and Stephen Chicione, Holocaust: From the Ashes: 1945 and After (Woodbridge, CT: Blackbirch Press, 1998), 19–24. QUESTIONS 1. What difficulties did the Jews who survived the Holocaust face? 2. How did the nations of the world respond to the plight of Holocaust survivors? 3. How did the Holocaust contribute to the desire to create a Jewish homeland in Palestine? Aftermath 287 DOCUMENT 3C Photo: Exodus Protest In June 1946 the “illegal” immigrant ship Josiah Wedgewood was intercepted by the HMS Venus while attempting to run the British blockade of Palestine. The ship, carrying 1,300 European Jewish refugees, was taken to Haifa and her passengers transferred to a detention camp. They carried signs reading “We survived Hitler. Death is no stranger to us. Nothing can keep us from our Jewish Homeland. Our blood will be on your head if you fire on an unarmed ship.” Displaced Persons in the Bergen-Belsen DP camp carry banners and flags to a demonstration protesting the forced return to Europe of the Exodus, a ship carrying 4,500 Jewish refugees to Palestine. The Exodus became a symbol of the “illegal” Jewish immigration to Palestine after the Holocaust. 1947. (Gedenkstatte Bergen-Belsen, courtesy of USHMM Photo Archives) United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Photo archive QUESTIONS 1. How does the text below the photo and the photograph illustrate one of the major problems facing Jewish Holocaust survivors? 2. What contemporary examples are there of other people seeking asylum? 3. Is the United States or any other nation obligated to assist these people? 288 Aftermath DOCUMENT 4A War Crimes Trials More than 35 million people— most of them civilians—were killed in Europe during World War II. What treatment should be meted out to the Nazi leaders who had unleashed genocidal violence? The Allies weighed these questions at Nuremberg, Germany, the site of a series of war-crimes trials. On November 20, 1945, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson began the prosecution at Nuremberg. “The most savage and numerous crimes planned and committed by the Nazis,” he emphasized, “were those against the Jews.” “Hitler, Heinrich Himmler, and other major Nazi figures did not hear his words. They had escaped trial by committing suicide. Twenty-two other Nazis were in the dock, however, when the International Military Tribunal (IMT), consisting of judges from the Allied powers—-Great Britain, France, the USSR, and the United States—began its work. The Nazi defendants included Martin Bormann, Nazi party secretary and chief aide to Hitler, who was tried in absentia (he had not been found and was believed to be dead); Hermann Göring, who had authorized Reinhard Heydrich to prepare the “Final Solution”; Ernst Kaltenbrunner, head of the Security Police; Hans Frank, the Nazi governor of Occupied Poland; and Julius Streicher, a leading anti-Semitic propagandist. Jackson’s opening statement notwithstanding, the indictments against these men did not refer explicitly to crimes against Jewry. Instead, each of the Nuremberg defendants was tried on one or more of the following charges: (1) crimes against peace, (2) war crimes, (3) crimes against humanity, and (4) conspiracy to commit any of these crimes. The IMT acquitted three of the defendants. Twelve others—including Bormann, Göring, Kaltenbrunner, Frank, and Streicher—were sentenced to death by hanging. Seven more, including Albert Speer and others who had used concentration-camp prisoners as slave laborers, received prison terms. Under U.S. jurisdiction, 12 more trials were held at Nuremberg from October 1946 to April 1949. Indictments against Nazi war criminals led to trials in a variety of other courts, too. Nevertheless, only a fraction of the thousands directly involved in war crimes and the Holocaust were brought to justice. That shortcoming, however, does not diminish the essential contributions that those postwar trials made. They documented much that had happened, and their proceedings became a public record that continues to bear witness to the Holocaust. In addition, the trials established important principles: leaders can be held legally responsible for crimes committed in carrying out their government’s policies, and individuals cannot defend themselves by simply claiming that they had only obeyed orders. In the aftermath of the trials, the United Nations adopted a Convention for the Prevention of Crimes of Genocide as well as a Universal Declaration of Human Rights. David J. Hogan and David Aretha, eds. The Holocaust Chronicle (Lincolnwood, IL: Publications International, 2000), 634. QUESTIONS 1. What is a war crime? 2. Who should be held responsible for war crimes? 3. How did the Nuremberg trials address this issue of responsibility? 4. Why do you think the Allies decided to hold the trials in Nuremberg? 5. Do you think justice was served? Aftermath 289 DOCUMENT 4B The Nazi Hunter The 21 top-ranking Nazis who were captured immediately after the war were judged before the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg in 1945–1946. But other architects of the Final Solution, such as Heinrich Müller, head of the Gestapo; Hitler’s advisor Martin Bormann; and Alois Brunner, SS deportation expert, remained at large. Not content with government agencies’ often slow efforts to track down these war criminals, several individuals took matters into their own hands. Many devoted their entire lives to finding high-ranking Nazi officials and bringing them to justice. One of the most famous Nazi hunters was Simon Wiesenthal, born in 1908, in a small town in Galicia, now western Ukraine. Wiesenthal had lost 89 family members in the Holocaust. He himself had spent four-and-ahalf years in concentration camps. In 1945, he emerged from the Mauthausen labor camp a skeleton, weighing less than 100 pounds. Wiesenthal then worked with the U.S. Army, helping to track down war criminals in Austria. As part of his work, he accumulated lists of suspected criminals and recorded eyewitness accounts of Nazi atrocities. In 1947, Wiesenthal set up a small “Documentation Center” in order to help Jews locate missing relatives. In the process, he began building an extensive file of suspected war criminals’ names, known or presumed addresses, and witnesses to their crimes. By accumulating extensive evidence against them and writing countless letters to governments urging them to prosecute war criminals, he built a reputation as one of the most relentless and effective Nazi hunters. Over the years, he helped to locate and bring to trial more than 1,100 suspects. “I do this because I have to do it,” Wiesenthal once said. “I am not motivated by a sense of revenge.” One of Wiesenthal’s greatest successes was bringing about the capture of Franz Stangl, the former commandant of the Sobibor and Treblinka death camps in Poland, where more than 1 million people were murdered. On December 22, 1970, Stangl was sentenced in Germany to life in prison “for having supervised the murder of at least 900,000 men, women, and children.” He died in 1971. Eleanor Ayer and Stephen Chicione, Holocaust: From the Ashes: 1945 and After (Woodbridge, CT: Blackbirch Press, 1998), 46–47. QUESTIONS 1. Why did Wiesenthal feel it was necessary to pursue and prosecute high-ranking Nazis? 2. Should high-ranking Nazis continue to be pursued and prosecuted? Why? Why not? 290 Aftermath DOCUMENT 4C The Most-Wanted Nazi One of the highest-ranking Nazis still at large after the war was Adolf Eichmann, an SS lieutenant colonel who had arranged the transportation of millions of Jews to death and concentration camps. In order to demonstrate Eichmann’s knowledge of, and participation in, Hitler’s “Final Solution,” Wiesenthal told of a report from a Nazi meeting in Budapest, Hungary, in 1944. Some of Eichmann’s cohorts asked how many Jews had been exterminated thus far. When Eichmann responded “5 million,” they asked if he were nervous about what might happen to him when Germany lost the war. Reported Wiesenthal: Eichmann gave a very astute answer that shows he knew how the world worked: “A hundred dead people is a catastrophe,” he said. “6 million dead is a statistic.” Eichmann—who had been caught by the Americans and then let go—fled from Europe with a passport issued by the Vatican under the name Ricardo Klement. For years, Wiesenthal and other Nazi hunters sought in vain for traces of him. Finally, in May 1960, they caught Eichmann in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and delivered him to Israel. On May 23, Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion publicly announced that Adolf Eichmann had been brought to Jerusalem and would stand trial. At the trial, the chief prosecutor read the counts against Eichmann, numbering 15. At the end of each, the defendant was asked how he pleaded. Each time, Eichmann responded, “Not guilty.” Wrote Wiesenthal later: I thought that Eichmann should have been asked six million times, and he should have been made to answer six million times. The Eichmann trial, which was televised to much of the world, lasted from April 11 through December 15, 1961. One hundred witnesses for the prosecution—90 of whom were survivors of the Holocaust—took the stand. Eichmann himself also testified. In the end, he was found guilty on all counts and was sentenced to death by hanging. Eleanor Ayer and Stephen Chicione, Holocaust: From the Ashes: 1945 and After (Woodbridge, CT: Blackbirch Press, 1998), 47-48. QUESTIONS 1. How did the attitude expressed by Eichmann, “6 million dead is a statistic,” enable the Nazis to carry out the “Final Solution”? 2. Why do you think the Israelis decided to televise the Eichmann trial in 1961? Aftermath 291 DOCUMENT 5 “The Hangman” by Maurice Ogden 1. Into our town the Hangman came, Smelling of gold and blood and flame, And he paced our bricks with a different air And built his frame on the courthouse square. The scaffold stood by the courthouse side, Only as wide as the door was wide; A frame as tall, or little more, Than capping sill of the courthouse door. And we wondered, whenever we had the time, Who the criminal, what the crime, The Hangman judged with the yellow twist, Of knotted hemp in his busy fist. And innocent though we were, with dread We passed those eyes of buckshot lead; Till one cried: “Hangman, who is he, For whom you raise the gallows-tree?” And we cried: “Hangman, have you not done, Yesterday, with the alien one?” Then we felt silent, and stood amazed: “Oh, not for him was the gallows raised…” He laughed a laugh as he looked at us: “Did you think I’d gone to all this fuss To hang one man? That’s a thing I do To stretch the rope when the rope is new.” Then one cried “Murderer!” One cried “Shame!” And into our midst the Hangman came To that man’s place. “Do you hold,” said he, With him that was meat for the gallows-tree?” And he laid his hand on the one’s arm, And we shrank back in quick alarm, And we gave him way, and no one spoke Out of the fear of his Hangman’s cloak. Then a twinkle grew in the buckshot eye, And he gave us a riddle instead of reply: “He who served me the best,” said he, “Shall earn the rope on the gallows-tree.” That night we saw with dread surprise The Hangman’s scaffold had grown in size. Fed by the blood beneath the chute, The gallows-tree had taken root. And he stepped down, and laid his hands On a man who came from another land— And we breathed again, for another’s grief At the Hangman’s hand was our relief. Now as wide, or little more, Than the steps that led to the courthouse door, As tall as the writing, or nearly as tall, Halfway up on the courthouse door. And the gallows-frame on the courthouse lawn By tomorrow’s sun would be struck and gone. So we gave him way, and no one spoke, Out of respect for his Hangman’s cloak. 2. The next day’s sun looked mildly down On roof and street in our quiet town And, stark and black in the morning air, The gallows-tree on the courthouse square. And the Hangman stood at his usual stand With the yellow hemp in his busy hand; With his buckshot eye and jaw like a pike And his air so knowing and businesslike. 292 3. The third he took—we had all heard tell— Was a usurer and infidel, And “What,” said the Hangman, “have you to do With the gallows-bound, and he a Jew?” And we cried out: “Is this one he Who has served you well and faithfully?” The Hangman smiled: “It’s a clever scheme To try the strength of the gallows-beam.” The fourth man’s dark, accusing song Had scratched our comfort hard and long; And “What concern,” he gave us back, “Have you for the doomed—the doomed and Black?” Aftermath DOCUMENT 5 (continued) “The Hangman” by Maurice Ogden The fifth. The sixth. And we cried again: “Hangman, is this the man?” “It’s a trick,” he said, that we Hangmen know For easing the trap springs slow.” And he whistled his tune as he tried the snap And it sprang down with a ready snap And then a smile of awful command, He laid his hand upon my hand. And so we ceased, and asked no more As the Hangman tallied his bloody score; And sun by sun and night by night, The gallows grew to monstrous height. “You tricked me, Hangman.” I shouted then, “That your scaffold was built for other men, And I’m no henchmen of yours,” I cried. “You lied to me, Hangman, foully lied!” The wings of the scaffold opened wide Till they covered the square from side to side: And the monster cross-beam, looking down, Cast its shadow across the town. Then a twinkle grew in the buckshot eye: “Lied to you? Tricked you?” he said. “Not I. For I answered straight and I told you true: The scaffold was raised for none but you. 4. Then through the town the Hangman came And called in the empty streets my name— And I looked at the gallows soaring tall And thought: “There is no one left at all For hanging, and so he calls to me To help pull down the gallows-tree.” And I went out with right good hope To the Hangman’s tree and the Hangman’s rope. He smiled at me as I came down To the courthouse square through the silent town, And supple and stretched in his busy hand Was the yellow twist of the hempen strand. “For who has served more faithfully Than you with your coward’s hope?” said he. “And where are the others that might have stood Side by side in the common good?” “Dead,” I whispered: and amiably “Murdered,” the Hangman corrected me: “First the alien, then the Jew… I did no more than you let me do.” Beneath the beam that blocked the sky, None had stood so alone as I— And the Hangman strapped me, and no voice there Cried “Stay!” for me in the empty square. Maurice Ogden, “The Hangman”. Reprinted from a study guide on the Holocaust (1999). Reprinted by permission. Georgia Commission on the Holocaust. QUESTIONS 1. What choices were open to the townspeople when the Hangman arrived? 2. Was there a way to stop the Hangman? If so, how? If not, why not? 3. How does the poem relate to Germany in the 1930s? To society today? 4. How is the point Niemöller makes his poem in Lesson 4 similar to the one Ogden makes in “The Hangman”? Aftermath 293 DOCUMENT 6 Universal Declaration of Human Rights The declaration below, adopted by the members of the United Nation’s General Assembly in December 1948, outlined its view on the human rights guaranteed to all people. Article 1 All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. Article 3 Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person. Article 4 No one person shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms. Article 5 No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Article 9 No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, detention or exile. Article 13 1. Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each state. 2. Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country. Article 14 Everyone has the right to seek and enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution. Article 15 Everyone has the right to a nationality. Article 18 Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion. Article 20 Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression. Article 21 Everyone has the right to take part in the government of his country, directly or through freely chosen representatives. http://www.un.org/overview/rights.html QUESTIONS 1. How is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights a response to the events of the Holocaust? 2. Is the United States or any other nation obligated to enforce it? Why or why not? 294 Aftermath DOCUMENT 7 “Ethnic Cleansing Center” New York State Education Department, Global Studies Regents Examination, June 1994, Part II, p.10. QUESTIONS 1. What do each of the headstones in the cartoon represent? 2. What is the main idea of the cartoon? 3. Choose three of the groups depicted in the cartoon. For each, what were the causes and events that led to the murder of many members of the group? Use specific historical information in your answer. Aftermath 295 DOCUMENT 8 “Riddle” by William Heyen From Belsen a crate of gold teeth, from Dauchau a mountain of shoes, from Auschwitz a skin lampshade, Who killed the Jews? Not I, cries the typist, not I, cries the engineer, not I, cries Adolf Eichmann, not I, cries Albert Speer. My friend Fritz Nova lost his father— a petty official had to choose. My friend Lou Abrahms lost his brother. Who killed the Jews? David Nova swallowed gas, Hyman Abrahms was beaten and starved. Some men signed their papers, and some stood guard, and some herded them in, and some dropped the pellets, and some spread the ashes, and some hosed the walls, and some planted the wheat, and some poured the steel, and some cleared the rails, and some raised the cattle. Some smelled the smoke, some just heard the news. Were they Germans? Were they Nazis? Were they human? Who killed the Jews? The stars will remember the gold, the sun will remember the shoes, the moon will remember the skin, But who killed the Jews? William Heyen, Erika: Poems of the Holocaust (St. Louis: Time Being Books, 1991), 42. 296 Aftermath DOCUMENT 8 (continued) “Riddle” by William Heyen QUESTIONS Read the poem aloud or silently two or three times. 1. What is the main impression, feeling, or point you get from this poem? 2. Choose at least three lines which support your answer to Question 1 and quote those lines. 3. Tell why those lines are particularly descriptive and explain how they support your answer to Question 1. 4. If the “Universe of Obligation” is an expression used to describe one’s sense of responsibility to others, what does “Riddle” make you think about? a. Who is to take responsibility for the Holocaust? b. How could individuals have made different choices and how might the outcome have differed? Aftermath 297 DOCUMENT 9 The Universe of Obligation SELF QUESTION Remember that you completed this diagram at the beginning of the unit. Fill it out again to see how you now perceive yourself and your obligation toward others. 298 Aftermath CONTEMPORARY CONNECTION AND HOMEWORK Something in Common: Horror Survivors Describe the Evils of Genocide Read the article and then answer the questions at the end. By Corey Kilgannon David Gewirtzman and Jacquueline Murekatete stood before a restless group of students at Great Neck North High School, waiting to tell their stories. They seemed to be an unlikely pair speaking on what seemed an unlikely topic—genocide—for a group of teenagers munching on sandwiches and rustling snack wrappers. By the time they had finished, however, the only sound that could be heard in the room was the faint hum of a radiator. Mr. Gewirtzman, a 75-year old retired pharmacist who lives in Great Neck, N.Y., On Long Island, survived the Holocaust by spending almost two years burrowed with other members of his family under a pigsty on a Polish farm. Now, he visits local schools, hoping that by telling of his experiences, he can educate students and help prevent a killing like the Holocaust from happening again. When he spoke at a high Aftermath school in Queens two years ago, Ms. Murekatete, then a student, was in the audience. She said his story had made her burst into tears. She wrote him a note relating her own horrible story, which took place in Rwanda, in central Africa in 1994. She narrowly escaped being hacked to death by a rival tribe. Her family—both parents and all six siblings—did not. “I finally found someone who understood what I went through because he went through the same thing,” said Ms. Murekatete, now 19 and a freshman at the State University at Stony Brook. Mr. Gewirtzman met the teenager, heard her story and suggested she begin speaking to groups with him. It would not bring her family back, he said, but it might save other families from potential genocide. It would also help to heal her own pain. “We are as different as can be,” he told the students. “She’s black, I’m white; she’s young, I’m old; she’s African and Christian and I’m a Jew from Poland. Yet we’re like brother and sister, because we’re bound by the common trauma of our experience and a common history of pain and suffering and persecution.” Now they appear regularly together, hoping that they can bring experience and relevance to a harsh subject. But neither expected the impression they would have on each other, and how deep their friendship would grow with the only apparent bond being death. Elaine Weiss, a history teacher at the high school who directs its social science research center, said she asked them to speak because “the kids can identify with an 18year old girl better than they can with a 75-year old man.” She said, “Our kids read theories about racism and genocide in books. But when they hear similar real-life stories from a white European man and a black African teenager 55 years apart in age, who lived through events 50 years apart in history, it’s not a theory anymore. It’s alive.” Mr. Gewirtzman grew up in a small village in Poland and in November 1942, the family persuaded a local farmer to 299 CONTEMPORARY CONNECTION AND HOMEWORK Something in Common: Horror Survivors Describe the Evils of Genocide hide them and some relatives—eight people in all—for 20 months in a small trench below a pigsty strewn with mud and pig waste. Day after day in the hole, they would argue whether to surrender to the Nazis, he recalled. “At times my father would yell at me, ‘Why did you lead us here? We should have gone to Treblinka and gotten it over with,’ “Mr. Gewirtzman said. “I’d tell him, ‘You must want to die, but don’t you want your children to live?’ Then he would snap out of it.” “We thought there wasn’t a Jew in Europe still alive, but for some reason, I never once doubted we would survive,” he said. “Maybe I was too young and naïve, but I never lost hope.” They did not escape until July 31, 1944, when the Nazis retreated. Mr. Gewirtzman and his family lived in Europe for several years, then came to the United States in 1948. He served in the United States Army in Germany. He and his wife have two 300 grown sons and he also volunteers at the Nassau Holocaust Memorial Center, in Glen Cove, Long Island. As Mr. Gewirtzman spoke, the students became spellbound. Some still held back tears as Ms. Murekatete began telling how she grew up as the second oldest of seven children on a family farm in Rwanda. Her family was members of a Tutsi tribe. In April 1994, when she was 9, the news came over the radio that the Hutu president had been killed. Groups of Hutu men and boys wielding guns, machetes and clubs began descending on the villages, killing Tutsis. The day they reached her village, Ms. Murekatete was visiting her grandmother Magdalene Mukasharangabo in a nearby village. Her grandmother saved her by taking her to an orphanage. After two months, she learned from surviving cousins that her family—her mother, father, two sisters and four brothers—had been tortured and hacked to pieces with machetes. Most of her other relatives were also killed, including her grandmother. She was brought to New York in October 1995, by an uncle who legally adopted her and applied for political asylum for her. She spoke only Kinyarwanda, but was placed in a fifth-grade class and soon learned English and began excelling in school. She said she still sees her family in her dreams. Other times, though, she is chased by men with machetes. “I’ve never gone to a counselor or a therapist,” she said. “At first, I guess I hoped it might just go away.” She said, “Some of my friends are afraid to ask me about it and I’m not a person who talks about my problems.” Ms. Murekatete is currently writing a book about her recollections of the genocide in Rwanda. She also said that last September, she met the human rights advocate Elie Wiesel at an International Day of Peace ceremony at the United Nations. After hearing her story, he hugged her and said he would help her publish it. With many cousins, aunts Aftermath CONTEMPORARY CONNECTION AND HOMEWORK Something in Common: Horror Survivors Describe the Evils of Genocide and uncles killed and only a few relatives left, Ms. Murekatete has grown close to Mr. Gewirtzman and his wife, Lillian, a Polish Jew, who had been sent with her family to Siberia for six years while Russia occupied Poland. Ms. Murekatete visits their home in Great Neck and has been to their summer home in the Hamptons. The Gewirtzmans went to her high school graduation, and she had tears in her eyes. “I didn’t know what to do with my experience and he showed me,” she said when asked about that day. Mr. Gewirtzman said, “In a way we’ve become sort of parents to her.” “We both went through a traumatic experience,” he said, “but instead of remaining bitter and angry and seeking revenge, we both resolved to spend the anger in a positive manner, to prevent this from ever happening again.” Ms. Murekatete shows listeners that racial hatred has outlived the Holocaust, and that genocide was not just something that happened to an old Jewish man from Poland, he said. “When I go to an inner–city school, the kids might think they have nothing in common with some Jews 60 years ago, or me with slavery,” he said. “But when they see both of us, they see the problem is the same,” he said. “It transcends race and ethnicity. People are still being taught hatred and it is hatred that we are fighting.” Ms. Murekatete said, “Sometimes students ask if they can help, and I say, ‘The best thing you can do for me is to educate yourselves so this New York Time, January 14, 2004, B1-2. QUESTIONS 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Give 3 important details about David Gewirtzman’s experience. Give 3 important details about Jacqueline Murekatete’s experience. Describe why these two are an unlikely pair and explain what has drawn them together. Describe the conversation David had with his father while they were in hiding. Describe Jacqueline’s situation in Rwanda in 1994. Having read about two very different survivors, compare and contrast their survival experiences, and the contributions, if any, of those who helped them. Aftermath 301 REFERENCES Ayer, Eleanor, and Stephen Chicione. Holocaust: From the Ashes: May 1945 and After. Woodbridge, CT: Blackbirch Press, 1998. . Dawidowicz, Lucy S., The War Against the Jews. New York: Henry Holt & Co., Inc. 1962. Dwork, Deborah, “My War Began in 1945.” in Images of the Holocaust: A Literature Anthology, ed. Jean E. Brown, Elaine C. Stephens and Jane E. Rubin. Lincolnwood, IL: NTC, 1997 Gilbert, Martin. Atlas of the Holocaust. New York: William Morrow, 1983. Originally published 1960. Heyen, William. “Riddle.” In Erika: Poems of the Holocaust. St. Louis: Time Being Books, 1991. Hogan, David J., and David Aretha, eds. The Holocaust Chronicle: A History in Words and Pictures. Lincolnwood, IL: Publications International, 2000. Ogden, Maurice, “The Hangman.” Reprinted from a study guide on the Holocaust (1999). Georgia commission on the holocaust. Wiesel, Elie. Night. New York: Bantam. 1982. 302 Aftermath