The Responsible Employer

The

Responsible Employer

Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

Preface

I am delighted to be able to introduce this report to you on behalf of Working Links.

The Responsible Employer considers how the challenge of addressing unemployment amongst disadvantaged people might be tackled through corporate responsibility (CR): the ways in which an organisation manages its business processes to produce an overall positive impact on society.

Specifically, we examine how the

CR function could work for the benefit of the individuals who are given assistance; the employers who provide that assistance; and ultimately, for the social and economic wellbeing of the UK as a whole. Finally, we also consider how CR could do more to develop and promote the kind of dedicated employability schemes through which people with disadvantages can be helped to find lasting and fulfilling employment.

2

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

We live in almost uniquely challenging economic times and so we are calling on employers to think more proactively about their role in helping those people furthest from the labour market to overcome the barriers they face to employment. Socially responsible – yes; but we also highlight the benefits that such efforts can bring to businesses in terms of improved staff loyalty, employee morale and reputation.

CR is now a developed business function and, as our research shows, it is a function in which businesses have continued to invest despite the difficult economic climate. We believe that, as CR matures, it can move beyond its current heavy emphasis on environment and sustainability – important though these considerations are. Increased

CR activity which supports people with disadvantages to enter and prosper in the workplace has the potential to promote greater social inclusion and mobility and to contribute to future economic growth. As the evidence in this report makes clear, high levels of unemployment

– and in particular persistently high levels of youth unemployment – incur an enormous financial cost on the taxpayer and an incalculable social cost on those communities blighted by worklessness.

We recognise that our ambition to see such employability initiatives universally championed by business as a key corporate responsibility is unlikely to be realised quickly: extensive adoption of dedicated employability programmes will take time.

Neither do we claim that ‘employability as

CR’ offers a short-cut solution to economic recovery: programmes that address social exclusion are vital but they cannot operate in a vacuum; and to have a significant impact on levels of unemployment, employability as

CR must run alongside government policies aimed at creating jobs and delivering growth.

Since 2000, Working Links has helped nearly a quarter of a million people into work. We have done this through times both of economic growth and of economic difficulty – and we are proud of every single instance in which we have helped a person change their life through sustainable employment. However, today – with the UK facing an uncertain economic future – we believe that the work we do in partnership with government, our supply chain and customers, has never been more important.

It is our conviction that the vision of responsible employment set out in this report has the potential to yield economic and social benefits at a national level, and life-changing benefits at an individual level.

We call on government, employers and our fellow specialist employment services organisations, to redouble their efforts – to work more closely and effectively together to narrow the ‘employability gap’ and so enable people from disadvantaged backgrounds to enter work and to make progress once there.

Work is at the heart of a responsible society; it is our responsibility to see that everyone in society is given their chance to build a working life.

Millie Banerjee

Chairman

Working Links

3

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

Foreword

We at Business in the Community

(BITC) appreciate this timely report and welcome its findings. We work to support and challenge our member companies to put responsible business practice right at the heart of what they do.

Creating and nurturing a diverse, healthy and engaged workforce that draws talent from the widest possible pool, including people who are currently furthest from the workplace such as homeless people, care leavers, ex-offenders or people who lack qualifications, is a vitally important part of doing that.

Responsible businesses do not view this activity as a bolt-on CR initiative, but something that lies at the heart of their business plan and ultimately helps them create value by living their values. It can be hard to do, the right thing often is, but we do know that taking these actions can actually help an employer’s bottom line by creating a more reliable and loyal workforce, improving the morale of all of its employees and its customers’ perception of its brand.

We know from our own national Ready for

Work programme, which has supported over 2,400 people into work, that society benefits from tackling this issue. We have calculated that, for every pound invested, our scheme can deliver a £3.12 benefit to society by removing people from a costly cycle of benefits, unemployment, ill health and potentially crime.

But the pressures facing business decision makers are many and complex, and causes have to compete strenuously for attention.

We believe that everyone, particularly people with significant barriers to overcome, should receive support from business to build the skills and confidence they need to gain and sustain employment. The companies that are already doing this are reaping the benefits, and we need them to share their experiences with more companies to help them see the value of recruiting an ex-offender, or someone trying to break the cycle of homelessness. For over 15 years we have been helping companies develop their employability work with disadvantaged groups and then build it into their core business. We currently work with 140 businesses in 20 cities providing training, work placements and post-placement support to help them overcome the barriers to lasting employment.

We fully support the call to action that every employer should review their HR and CR policies to ensure that these incorporate recruitment and training programmes to help disadvantaged people into work. We also welcome the call on businesses to consider the extent to which their supply chain reflects their values with regard to helping people with disadvantages into work. Finally, we repeat and echo the call on employers who have enjoyed the benefits of running employability programmes to act as advocates for work inclusion.

Stephen Howard

Chief Executive

Business in the Community

4

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

Contents

Methodology 6

Terms of reference 6

Executive summary

Introduction: The case for employability as CR

The business case for CR

The benefits of employability programmes for businesses

A shared objective – employability as CR

Why CR as employability matters now

8

12

14

16

17

18

Section 1: What is CR all about?

The dominance of the green agenda

CR activity that supports people into work

Analysis: Why the green agenda has been so successful

Section 2: The business benefits of employability programmes

The wider case for employability as CR

19

20

21

22

23

27

Section 3: Employability as CR: the barriers that make it challenging

Analysis: the barriers that make it harder to recruit from disadvantaged groups

The role of the government

Helping people furthest from the labour market

Employability as CR: large employers

Analysis: a national solution from national employers?

CR for SMEs

Analysis: SMEs, employability and CR

Section 4: CR through the supply chain

Analysis: setting a recognised standard for employability programmes

41

44

Conclusion 45

Appendices 47

Appendix 1: Case studies 47

Appendix 2: Background to the Ready for Work programme 48

Bibliography 51

29

32

33

36

38

39

39

40

5

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

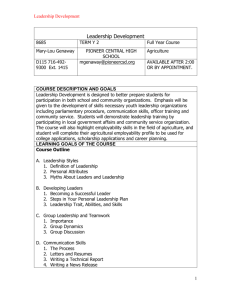

Methodology Terms of reference

In December 2011

Working Links conducted two online surveys. We polled 150 HR managers across businesses of all sizes. We also polled

50 CR managers.

Alongside this online research we spoke to a number of experts in

CR functions and in employability.

Together with our experience of helping nearly a quarter of a million people into work, this research is the foundation of our report.

Corporate Responsibility

For the benefit of respondents to our survey for this research, Working Links defines CR as:

The ways in which an organisation manages its business processes to produce an overall positive impact on society.

Working Links’ own ‘Getting it Right’ strategy embeds our three sustainability aims – to be socially driven, commercially sound and environmentally responsible – into the DNA of our business. Although we refer to corporate and social responsibility as CR throughout this report, we recognise that many organisations refer to their CSR activity and we do not distinguish between CR and CSR.

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

Employability

Hillage and Pollard 1 define employability in the following way: “In simple terms, employability is about being capable of getting and keeping fulfilling work. More comprehensively, employability is the capability to move self-sufficiently within the labour market to realise potential through sustainable employment. For the individual, employability depends on the knowledge, skills and attitudes they possess, the way they use those assets and present them to employers and the context (e.g. personal circumstances and labour market environment) within which they seek work”.

Working Links believes that people can enhance, and indeed in some cases transform, their quality of life through sustainable employment. We therefore encourage any activity that will improve an individual’s employability – such as career development programmes, training and ongoing education. We also encourage activity on a macroeconomic scale which will improve a society’s general employability, for example job creation, a dynamic labour market, improved protection for employees and so on. Employability can be enhanced in school children and pensioners as well as people of working age, and anybody from a teenager gaining work experience to a chief executive learning a new language can, and should, look to improve their individual capacity to thrive in their working life.

However, in the context of this report, references to employability and employability programmes or schemes, are concerned with improving the employability of people furthest from the labour market – those people who, for whatever reason, are disadvantaged when competing to find work.

Disadvantaged groups

Business in the Community (BITC) defines disadvantaged groups as those people who face barriers to employment as the result of one or more of the following experiences:

– experience or risk of homelessness;

– moving from custody, the armed services or asylum support accommodation;

– leaving care;

– substance misuse;

– domestic violence;

– disability (including health, mental health and learning disabilities); and

– long-term unemployment.

The focus of this report is how employers can help people in these disadvantaged groups into work – but especially so if people from the above categories have been long-term unemployed. For the benefit of respondents to our survey we used the following definition: “Disadvantaged people are defined as those long-term unemployed people who are deprived of some of the basic necessities or advantages of life, and includes people with disabilities, learning difficulties, the low-skilled, or those from deprived areas.”

Therefore, in the context of this report, we consider ‘people from disadvantaged groups’ to be people who face barriers to employment as a consequence of their disadvantages.

However, we recognise that not everyone who falls into one or more of the categories above is necessarily disadvantaged, and that there are those who are not deprived of the basic necessities or advantages of life who choose not to work.

1 Hillage and Pollard (1998)

7

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

Executive summary

Working Links commissioned this research report to explore the extent to which businesses are engaged in programmes which help people from disadvantaged groups

2

into sustainable employment, and how such programmes fit into the wider corporate and social responsibility

(CR) activity of businesses.

We did so because we believe that if more businesses were to offer employability programmes

(sometimes referred to as work inclusion) this would benefit not only the businesses themselves but the communities in which they operate, and the UK as a whole.

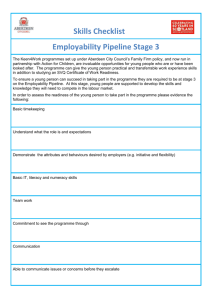

For the purpose of this report, employability programmes and schemes are those specifically aimed at helping people from disadvantaged groups to gain the skills, training and confidence they need to find lasting and fulfilling employment.

3

To inform this report, Working Links surveyed

HR managers and CR managers across a range of sectors, and in businesses of all sizes. Our original research, together with existing research and the interviews and conversations we have had with a range of experts in CR practices, have shaped the content and conclusions of this report, which has three clear aims:

– to show the business and reputational benefits of employability as a component of CR;

– to explore how businesses can overcome some of the barriers that make it challenging to actively recruit from disadvantaged groups; and

– to assert that employability as a component of CR has the potential to bring wider economic benefits to the UK by addressing the causes and consequences of long-term unemployment, especially youth unemployment.

2 The terms ‘disadvantaged groups’ and ‘disadvantaged people’ are used throughout this report – please see the terms of reference at the front of this report for a fuller description of the term within the context of this report

3 For a fuller definition of employability please see the terms of reference at the front of this report

8

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

Employability as a component of CR

CR activity has become a business-critical function in successful organisations.

From its origins in the philanthropy of business leaders in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, it has evolved to be a central pillar of how businesses continue to secure a ‘licence to operate’ and of how they protect and enhance their brand equity and reputation.

Our research shows that the principal focus of current CR activity is around making businesses environmentally sustainable.

Other elements of CR include community initiatives, ethical sourcing, donating to charity and employability programmes. While our research shows that many businesses are engaged in employability schemes, they were only the top priority for 12% of respondents to our survey (compared to 36% who ranked “environment” top).

However, as sustainability becomes a prerequisite for all business functions, we believe that over time, the environment will feature less as a CR priority, as ‘green’ activity (which would historically have been voluntary CR activity) becomes mandated by national and European laws. And just as some businesses have enhanced their reputation through policies that promote their responsible approach to the environment, we believe that forward-thinking businesses could – and should – take immediate steps to enhance their reputation as responsible employers, by incorporating employability into their CR programmes.

Our research shows that, where businesses do have employability schemes, they are seeing tangible business and reputational benefits. Respondents to our survey who have implemented employability programmes cited a range of business benefits including: “a more reliable workforce”

(51%), “a more loyal workforce” (47%) and

“improved employee retention” (44%).

However, our research shows a disparity between the views of HR managers and

CR managers as to the perceived benefits of integrating recruitment programmes into employability as CR. Some 73% of

CR managers we surveyed said that they did not see the value in actively recruiting from disadvantaged groups while, of the

HR managers who do run employability programmes, 84% saw it as part of their

CR. And even among those HR managers yet to run employability programmes, 58% said that they could see the benefits.

We conclude from this that, because recruitment policies are the clear responsibility of HR departments, the full CR benefits of employability programmes are not as widely known or as well understood as more prominent CR activities around, for example, the environment, community initiatives and ethical sourcing. Employability is not yet part of the regular canon of CR activity – and as such it does not feature as a high priority for CR managers, who would be unlikely to extol the merits of CR activity they have chosen not to pursue.

However, because the evidence shows that employability programmes bring business benefits and reputational benefits, we believe that many more businesses should embrace employability programmes as a strand of their CR activity. The case studies in this report reflect the fact that some of the UK’s best known and most successful businesses have recognised the benefits of employability as CR and have put in place programmes to deliver them.

9

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

Working Links has helped almost a quarter of a million people turn their lives around by finding fulfilling and lasting work. For the people we have helped into work, the benefits are incalculable. However, effective employability schemes have the potential to have an impact beyond the individuals helped into sustainable employment. The

HR managers we surveyed overwhelmingly consider it a duty for employers to help the

UK address economic (90%) and societal challenges (81%). Addressing the cost to the

UK taxpayer of long-term unemployment is vital if the UK is to continue to compete in the twenty-first century global economy.

Youth unemployment poses a particular problem, a “time-bomb under the nation’s finances”, 4 which is estimated to cost the taxpayer £4.2 billion in benefits, £600 million in taxes foregone and £10.7 billion in lost economic output. Aside from the measurable costs in pounds and pence, there is a huge social cost from unemployment, as the violence of the riots in London and elsewhere in 2011 alarmingly revealed.

5

Addressing the barriers

Although our research indicates that policies to actively recruit from disadvantaged groups will bring business and reputational benefits, we recognise that employability programmes can be challenging to implement. The employers we surveyed expressed concerns over the quality of the workforce (60%), the cost of training involved in employability schemes (58%) and the cost in time and money of recruiting from a specific group of people (35%). The majority of employers also expressed concerns about matching the skills they need from their employees to recruits who have, for example, been long-term unemployed (70%).

Working Links does not believe that if businesses were persuaded of the benefits of employability as CR then long-term unemployed people, and people with other disadvantages, would be swiftly and easily employed. Nor do we believe that, for large employers engaging in government sponsored schemes to help unemployed people, there are no risks to those employers’ reputations. But neither do we believe that the barriers to extensive adoption of employability programmes are insurmountable. At a time of low economic growth, government and employers must be more proactive in helping people who struggle to find sustainable employment. The solution lies in government and employers working together, along with specialist employment services organisations, to match the employment needs of industry to those people who are furthest from the labour market. With the right skills, training and confidence, employers and training providers can narrow that ‘employability gap’ so that people from disadvantaged backgrounds are in a position to secure a job and make good progress in their working life.

4 ACEVO (2012)

5 83% of respondents to the

Riots Communities and

Victims Panel report, After the Riots , felt that youth unemployment was a problem in their local area

10

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

The fact that some large national employers have already embraced employability programmes and incorporated them into their other CR activity reflects the fact that many businesses see the benefits to themselves, their reputation and the wider society they serve. Working Links commends those large national employers who have shown the benefits of employability as CR, but we believe that their example could be replicated on a much larger scale by a wider range of employers.

CR through the supply chain

Not all businesses will be able to establish programmes to actively recruit from disadvantaged groups. However, just as an employer of any size (as well as the sole trader, or even the individual consumer) is able to make a conscious decision to engage companies and products in its supply chain that meet exacting environmental standards; we believe that companies which offer employability as part of their wider CR repertoire could leverage this to appeal to new customers. Following the example of the fair trade movement, an employability

Kitemark could enable companies who make an active commitment to employability schemes to tangibly demonstrate a recognisable measure of commitment.

The responsible employer

We call on employers to adopt the following recommendations:

– Review CR strategies with a view to incorporating recruitment and training programmes which help people from disadvantaged groups into work.

– Review HR strategies with a view to embedding employability aimed at people from disadvantaged groups into their recruitment and training programmes.

– Consider the extent to which their supply chain reflects their values with regard to helping people from disadvantaged groups into work.

And:

– Where businesses operate employability as CR, to encourage their industry peers to do likewise and to extol the virtues of actively recruiting people from disadvantaged groups.

11

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

Introduction:

The case for employability as CR

78

%

of HR managers feel a responsibility to help address youth unemployment.

74

%

of CR managers believe employers have a responsibility to address high levels of unemployment.

81

%

of HR managers believe businesses have a duty to contribute to addressing societal problems faced by the UK.

12

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

The UK in 2012 faces unprecedented economic challenges. Unlike the recessions of the 1980s and 1990s, we are in the midst of a global jobs crisis. Unemployment is high, and youth unemployment is higher than it has ever been.

The global economic collapse triggered by the financial crisis of 2008 more closely resembles The Depression of the 1930s (and by some measures is more severe) than the cycle of boom and bust which successive governments failed to break in the post-war era. At a time when jobs are scarce, people from disadvantaged groups are pushed even further away from the labour market, limiting their prospects of finding lasting work. For young people the labour market is especially challenging, and it is with reason that commentators and politicians have raised concerns about a ‘lost generation’ of young people unable to make the transition from education to employment. If the UK is to build a lasting economic recovery it must be built on solid foundations, including a renewed commitment to assist people who are hardest to help into work. Such times call for radical new solutions. We believe that promoting employability as a corporate responsibility is one such solution.

This report sets out our vision as to how businesses could incorporate programmes and policies to help people from disadvantaged groups 6 into work as part of their wider commitment to behave as socially and corporately responsible organisations. We will also show that embracing employability as CR can deliver material business benefits at the same time as addressing the long-term economic consequences of high unemployment.

6 The terms ‘disadvantaged groups’ and ‘disadvantaged people’ are used throughout this report – please see the terms of reference at the front of this report for a fuller description of the term within the context of this report

13

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

The business case for CR

The European Union 7 defines CR as:

“A concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and in their interaction with their stakeholders on a voluntary basis.”

For as long as there have been businesses, there have been concerns about the impact that a business has on the environment and amongst the communities in which it operates. CR cannot be confined to activity which is a prerequisite for a licence to operate. For example, a business which is permitted to pump waste water into the sea under certain conditions cannot claim that it is voluntarily behaving in a responsible manner by taking the trouble to clean waste water before dumping it. Similarly, employers who abide by the Working Time Directive cannot claim to be integrating concern for the workforce into their business operations because they are obeying the law. Finally, while acts of generosity such as charitable giving are positive initiatives which should be welcomed, they should not strictly be seen as CR unless they directly impact upon and change the core practices of the business.

BITC, a business-focused charity concerned with promoting responsible business practice, has identified over

60 employer benefits from being a responsible business. It has grouped these under seven key categories: 8

– brand value and reputation;

– employees and future workforce;

– operational effectiveness;

– risk reduction and management;

– direct financial impact;

– organisational growth; and

– business opportunity.

Businesses are increasingly conscious that their brand equity and reputation are critical to business success, and that CR plays an important role in enhancing that value. McKinsey’s Global Survey of Chief

Financial Officers (CFOs) bears this out; when asked how environmental, social and / or governance programmes improve a company’s financial performance, 79% of

CFOs cited “maintaining a good corporate reputation and / or brand equity”.

9

7 European Union (2011)

8 Business in the Community

(2011a)

9 McKinsey (2009)

14

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

Does business have a duty to contribute towards tackling the UK’s problems?

81%

Yes

90%

Yes

Societal problems Economic issues

CR policies also help to drive trust in an organisation. The Edelman Trust Barometer shows the link between CR and trust, and the fact that both have become more important to an organisation’s stakeholders in recent years. In 2006, 42% of Edelman’s respondents cited strong financial performance as a driver of trust in their company, compared to 33% who cited social responsibility. Four years later, the relative importance of responsible behaviour had increased. “In 2010 public trust in companies was least affected by financial performance (only 45% of respondents cited this as important to corporate reputation), whereas 64% cited good corporate citizenship and 83% cited transparent and honest practices as important to corporate reputation”, a trend driven by a reduction in the public’s trust in business and government since the financial crisis of 2008.

10

Evidence from our survey also bears out the growing importance of CR to businesses.

Despite the challenging economic conditions, only 6% of the HR managers we surveyed had seen their organisation’s CR investment fall in the last five years. 21% said that their budgets had stayed the same, and 64% had seen CR budgets increase.

The financial crisis of 2008 and the global recession which followed have undermined trust in many businesses in trust of politicians and the media.

12

11 – compounded in the UK by the collapse

This has driven businesses to invest in building trust amongst stakeholders, and it seems likely that, whereas CR spending was an optional extra a decade ago, it is more important in the light of the financial crisis. CR in 2012 has moved a long way from the benevolence and philanthropy of the early industrial era and become a business-critical function. The most successful businesses have not only accepted the role CR plays in enhancing brand equity and reputation – they have embraced it.

10 Edelman (2010)

11 Edelman (2012)

12 The Edelman Trust

Barometer 2012 reflects a small rise in trust of media among its respondents.

However, in the UK the phone hacking scandal of

2011 further eroded trust. http://www.guardian.co.uk/ media/2011/nov/14/phonehacking-public-trust

15

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

The benefits of employability programmes for businesses

Employability describes an individual’s capacity to gain and maintain employment.

Working Links is an organisation that is committed to ensuring that individuals can optimise their employability and so fulfil their potential by securing sustainable employment. Our employability programmes address the factors that contribute to an individual’s low employability by giving people the basic skills and confidence to find that lasting job.

Employers look for employees with high employability – those candidates who have the right skills to succeed in the job and to progress within a business. Because it is highly valued by employers, many seek to enhance employability in their own workforce through training, mentoring and career development programmes.

Working Links strongly encourages businesses to invest in up-skilling their existing workforce because it not only enhances their productivity, it also allows for career progression – creating further vacancies for people looking for work.

However, this report seeks to set out the benefits of businesses actively integrating recruitment programmes that target disadvantaged individuals who are typically furthest from the labour market.

In the context of this report references to employability and to employability schemes and programmes refer specifically to activity aimed at helping people from disadvantaged groups to gain the skills and confidence they need to obtain lasting and fulfilling employment.

13 The evidence shows that there are identifiable business benefits of embracing recruitment policies that help these groups. Recent research 14 found that the impact of work inclusion was most keenly felt amongst the existing workforce:

75% of companies surveyed found that

“employee motivation / morale” increased among companies on their work inclusion programme.

15 The evidence also reflects the value of employability programmes in terms of brand reputation and value –

82% of companies running employability programmes for disadvantaged groups said that it improves the public perception of their company.

16 Material benefits for businesses include reductions in recruitment, training and overtime costs. Finally, 57% of businesses “reported benefits relating to organisational growth such as winning tenders and developing new partnerships.” 17

13 For a more detailed definition of employability please see the terms of reference at the front of this report

14 Business in the Community

(2011b)

15 lbid

16 lbid

17 lbid

16

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

A shared objective – employability as CR

CR is no longer the mark of a business that is prepared to go the extra mile in good times in order to make customers feel better about engaging with them. Nor is CR the preserve of those businesses that seek to practice

(as well as preach) the societal benefits of ethical behaviour. It is now a core business function, and its practitioners are expected to deliver a return on investment for the time and resource absorbed by CR activity.

Just as CR is now a core function, so is employability – although amongst employers it is not a commonly used term.

All employers are interested in hiring the most suitable candidates for their jobs and so, to some extent, all employers assess employability. The best employers also seek to enhance the employability levels of their staff through training and career progression. Much of this business function is currently incorporated into HR, which is why we chose to survey HR managers as a specific group. However, employability is not a pure measure of skills or potential, because an individual’s employability also depends on the context in which he or she is seeking work. Nobody would question the skills required to be a blacksmith, but their employability in central London is not directly linked to their motivation, presentation or confidence. Employers that seek to engage in employability programmes are, therefore, linking their business need to fill vacancies and the context in which they are hiring.

For example, when Travelodge chooses to hire directly from Jobcentre Plus it is creating jobs – performing its necessary HR function and addressing a lack of employability among potential candidates by targeting long-term unemployed people. Because such a policy addresses the employability gap, 18 Travelodge is doing more than simply hiring new staff and creating new jobs through socially responsible recruitment policies. It is also creating the economic space where the community in which it operates enjoys enhanced employability: a business which invests in training and career progression for its workforce in turn creates further job opportunities for local people.

Employability as CR brings the HR function and the CR function together and harnesses their shared objectives. Businesses want to promote themselves to their stakeholders as responsive to the needs of the communities amongst which they trade, and as responsible towards the environment in which they operate. They also want to improve the employability of their workforce.

18 The employability gap refers to the gap in required skills, training and experience that exists between an individual and available jobs.

In other words, training or work experience can help to close the employability gap by giving an individual the skills they need to secure a job. Schemes which actively recruit from disadvantaged groups contribute to addressing the employability gap because they give, for example, long-term unemployed people a better chance of securing employment

17

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

It is the purpose of this report to show that investing in employability as CR will bring together those societal and business benefits.

Why CR as employability matters now

Laws to promote environmental or social responsibility are not new; there are laws from the earliest civilisations that restrict, for example, deforestation rights. Neither is the benefit to businesses of investing in the training of their future workforce; 19 the

Apprenticeship as a training model is far older than compulsory schooling. But the need for businesses to promote themselves as responsible employers is greater now than in recent years, 20 and the scale of the challenge in addressing the causes and consequences of unemployment has been more acutely felt in this recession than at any time since the 1930s.

As this report will show, some employers are already actively engaged in employability as CR. Many others are engaged in employability in some form or other without harnessing the potential benefits of integrating it into their CR programmes.

However, at times of economic strife, the benefits of programmes that help disadvantaged people are more keenly felt.

Long-term unemployment, and especially very high levels of youth unemployment, is a blight on society. By bringing employability programmes under the umbrella of CR, a business can truly integrate its business processes and have a positive impact on society. There can have been few occasions in our recent history when this has been as important as it is today.

19 Environmental historian

Professor Richard Grove cites evidence of laws to protect the ancient forests of

Ur in Sumer as long ago as

2700 BC. (1995 (Paperback

1996)). Green Imperialism; colonial expansion, tropical island Edens and the origins of environmentalism 1600-

1860 Cambridge University

Press, Cambridge and New

York, Studies in Environment and History series, 550pp; published in India, Pakistan and SE Asia by Oxford

University Press.

20 Edelman (2012)

18

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

Section 1:

What is CR all about?

76

%

of employers consider

“environment and sustainability” as their first or second CR priority.

64

%

of employers have seen CR budgets increased over the last five years.

12

%

of employers consider “recruiting from disadvantaged groups” as their top priority.

19

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

Businesses recognise the need to behave responsibly if they are to maintain or enhance their reputation, and they recognise that doing so brings clear benefits to their business. For the purposes of this research we asked businesses to rank the issues that were

CR priorities.

We identified five areas:

1. Environment and sustainability

2. Supporting the local community

3. Ethical sourcing

4. Charitable giving in the UK and abroad

5. Recruiting from disadvantaged groups

The dominance of the green agenda

Some 36% of respondents ranked

“Environment and sustainability” as their top priority, followed by “Supporting the local community” (24%), “Ethical sourcing” (20%) and “Charitable giving in the UK and abroad”

(16%). Only 12% of respondents considered

“Recruiting from disadvantaged groups” as their number one priority.

When we analysed which categories were a first or second priority, those figures became even more stark – over three quarters (76%) of respondents ranked

“Environment and sustainability” as either first or second, compared to two thirds

(66%) for “Supporting the local community”.

Some 28% considered “Recruiting from disadvantaged groups” a second rank priority. We are encouraged that more respondents (40%) ranked this first or second compared to charitable giving

(34%). Only 10% ranked “Recruiting from disadvantaged groups” as the least important category – fewer than for ethical sourcing (18%). Of course, ethical sourcing is not an issue for every business. However, despite the fact that “Recruiting from disadvantaged groups” was the lowest number one priority of the five options, it is clear that it is a major consideration as an additional priority. The results from this one question were clear – when forced to rank CR priorities our respondents consider that environmental issues are their primary

CR concern.

We then asked what other issues were of relevance to businesses from a list of 12, and in this case did not ask respondents to rank their answers but to tick all the options which applied to them. This data again showed the dominance of environmental causes – only

6% of respondents thought the environment was “of no interest” and 84% were already engaged in some form of ‘green’ CR activity.

20

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

CR activity that supports people into work

In choosing from the wider range of categories, many organisations did state that schemes to help disadvantaged people into work were part of their CR.

This reflects the fact that, when required to prioritise CR activity, respondents did not rank employability programmes as first order issues – however, when considering a broader range of possible activities, respondents could point to some activity in this area. 42% of respondents said that they were engaged in “Supporting unemployed people to access our vacancies”, although

30% thought this was “of no interest”. Over half of respondents were engaged in work that supports initiatives to help people into work in a number of areas: 72% have mentoring schemes, 64% have training and work experience initiatives and 62% are engaging with schools and training providers.

This reflects the fact that, while employability is not yet a first order issue for CR managers, it is a significant component of the actual activity they undertake.

Working Links supports the broadest range of policies that will help increase the employability of people from disadvantaged groups. While proactive recruitment from these groups would, in our view, be the most effective way in which CR activity could help reduce unemployment, we recognise that training and work experience initiatives, mentoring and outreach to schools and training providers all have very important parts to play. In some cases such initiatives can help people, especially young people, to avoid becoming unemployed in the first place.

What are employers’ top CR priorities?

Environment and sustainability

Supporting the local community

Ethical sourcing

Charitable giving

Recruiting from disadvantaged groups

0% 20 40 60 80 100%

21

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

Analysis: Why the green agenda has been so successful

Working Links supports activity which is environmentally sustainable and which will contribute to worldwide efforts to reduce carbon emissions – it is a key pillar in our own organisation-wide CR strategy. It is emphatically not the purpose of this report to criticise organisations that invest in environmental causes or to suggest that this activity should cease. However we believe that, over time, the environment should become part of every organisation’s core functions and not an added extra. In some cases increased regulation aimed at increasing energy and fuel efficiency will render elements of the green agenda obsolete in CR terms: that which has been mandated cannot indefinitely be considered as CR. We also understand that many efforts by businesses to ‘green-up’ their practices are motivated by a need to prepare for anticipated regulation. This is especially the case in the UK, where EU-wide regulation is geared towards meeting very ambitious targets for reduced carbon emissions by

20% before 2020 (20-20-20 programme).

In the twenty-first century the green agenda also makes very good business sense.

Rising fuel prices have driven efficiencies in organisations dependent on road transport

(the vast majority of retailers). Schemes to reduce fuel usage through greener trucks, smarter routing and more fuel efficient driving bring a clear dual benefit: the business is seen to be ‘doing its bit’ for the environment while its fuel consumption is falling. This same logic applies to the use of energy-saving practices across the board.

The fact that so many businesses invest in CR activity that focuses on the environment is to the credit of those campaigning organisations which have moved green activity from being niche to becoming mainstream. The leveraging of public opinion in favour of those political parties and businesses that take the environment seriously has made green practices the norm. We hope that, as more businesses embrace employability as CR, a similar journey can be replicated. At present, recruitment schemes targeted at disadvantaged people are not widespread

– as shown by the evidence from our research. However, because we believe that employability as CR brings direct material gains for businesses, and contributes to the wider economic health of the nation, it can readily make the transition from small scale programmes to a core part of the CR and HR function. If it does so, then just as has been the case with the green agenda, it will become part of the normal pattern of an employer’s behaviour – bringing huge benefits to businesses and to society on the way.

What do employers with employability schemes offer?

Mentoring schemes

Training and work experience initiatives

Engaging with local schools and training providers

0% 20 40 60 80 100%

22

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

Section 2:

The business benefits of employability programmes

77

%

of CR managers said that supporting employment initiatives in the community brought benefits to their business.

67

%

of employers who operate employability schemes see the benefits they bring to the local economy.

64

%

of those operating employability programmes report a more loyal workforce.

50

%

of those operating employability programmes report increased employee morale.

23

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

Only 12% of the businesses we surveyed considered recruiting from disadvantaged groups to be their top

CR priority. However,

43% of businesses in our survey had a policy of actively recruiting from disadvantaged groups.

And of those that did not, 58% thought that such policies would benefit their company.

Employability may not yet be a central pillar of CR, but over two fifths of businesses are engaged in it and, of the rest, a majority see the potential benefits.

The main commercial benefit to businesses, derived from employability programmes that help people from disadvantaged groups, is the impact on the workforce. Some 51% of respondents said that employability policies led to “a more reliable workforce”,

47% said that their policies helped create

“a more loyal workforce” and 44% said they have experienced “improved employee retention”. We also asked what other benefits were felt by companies which actively recruited from disadvantaged groups. 67% cited the contribution that their recruitment schemes made to the local economy, 58% cited the positive impact on the local community and 49% cited improving the local image of the business.

24

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

We also asked if businesses saw benefits from supporting employment initiatives in their community (as opposed to actively engaging in a programme within one’s own business) and 77% replied that they did. Businesses which actively recruit from disadvantaged groups told us that there were commercial benefits in terms of their workforce and that their support for employability programmes – whether direct (that is, in-house) or indirect – had a positive impact on the local community and their own standing within it.

We also asked respondents to describe the benefits of employability programmes in their own words. One said that recruiting from disadvantaged groups “allows us to draw on a pool of people we might not otherwise have access to.” Another said that “it gives the right impression among employees”, another that “it works – simple as that.” While many did cite operational or commercial benefits, most respondents were particularly conscious of the positive impact on their reputation: “the business is seen in a better light by the wider community”; “it is seen as very ethical”; “improved positive reputation”. And 60% of businesses with employability schemes choose to promote them on their website and elsewhere.

Our research is clear – businesses which have invested in employability see the commercial and reputational benefits and those which have yet to do so are aware that those benefits are real.

Our research confirms the findings of existing research. In 2011, 75% of companies polled 21 said that they saw increased employee motivation / morale when they introduced employability schemes. 82% of companies cited improved public perception of the company in terms of positive media coverage, winning awards and achieving public recognition. Companies cited material savings in terms of recruitment costs and opportunities for growth through access to new markets and new partnerships. Some companies cited the fact that they were engaged in work inclusion programmes as a unique selling point which gave them the edge in winning new business.

Among additional benefits cited was the wider economic contribution that such programmes can make: “A number of businesses recognise the positive impacts that work inclusion initiatives have on macro-level sustainable development.

Longer-term benefits such as meeting multi-stakeholder interests, licence to operate, reducing crime and contributing towards community cohesion were acknowledged by businesses as being important.” 22

What have been the benefits to your company of actively recruiting from disadvantaged groups?

21 Business in the Community

(2011b)

22 lbid

Positive impact on the local community

More loyal workforce

Strengthening the local economy

Increasing employee morale

0% 20 40 60 80 100%

25

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

Among HR managers who actively recruit from disadvantaged groups, the overwhelming majority of the employers we interviewed see it as part of their overall CR

(84%). It is clear from our research overall that HR managers are, for the most part, engaged in their company’s CR function – only 21% of HR managers said that they had very little involvement in setting or influencing

CR policy. Our findings suggest, therefore, a discrepancy between attitudes in HR departments versus those with responsibility for CR. A very high number of CR managers do not see the value in actively recruiting from disadvantaged groups (73%). This is at odds with the views of HR managers who have implemented employability programmes and enjoyed the benefits.

There may be a number of explanations for this difference of view. As this report has already shown, the current focus of

CR activity is around the green agenda or community initiatives. Employability is not yet in the regular canon of CR work, and CR managers would be unlikely to recommend the benefits of activity which they have chosen not to undertake. It is also clear that CR managers see recruitment policies as the firm responsibility of HR.

We asked CR managers “do you think that addressing high levels of unemployment through proactive policies should rightly be the responsibility of CR managers or

HR managers?”. And 76% of CR managers thought it was for HR to deal with.

Do HR managers see recruiting people from disadvantaged groups as part of their business’ CR policies?

84%

Yes

Do CR managers think proactive recruitment policies to employ disadvantaged people should sit with them?

76%

No

26

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

Working Links asserts that there is a further compelling benefit that respondents did not overtly cite – the benefits to the economy as a whole and to UK plc.

23 ACEVO (2012)

24 lbid

The wider case for employability as CR

Employability as CR is a concept that has yet to take hold in most of the organisations we surveyed. Given the competing attractions of the green agenda, community initiatives and ethical sourcing to enhance productivity, brand value and reputation; proactively recruiting long-term unemployed people, people with learning difficulties or ex-offenders has struggled to achieve mass appeal. Yet it is clear from our research that those organisations which have taken steps to do so have reaped the commercial and reputational benefits – 77% of the CR managers we surveyed said that supporting employment initiatives in the community brought benefits to their business.

Working Links asserts that there is a further compelling benefit that respondents did not overtly cite – the benefits to the economy as a whole and to UK plc. The vast majority of HR managers considered it a duty to help the UK address economic challenges (90%) and societal challenges

(81%). Many businesses have yet to see the direct link between recruiting long-term unemployed people and those wider, national benefits. People who spend years out of work inevitably incur significant costs to the taxpayer in terms of the benefits they receive. There is also a significant social cost: the cost of youth unemployment is especially acute – increasing a person’s likelihood of unemployment in the future, and the limitations that early unemployment place on their longer-term earning capacity. The cost to the taxpayer has been described as a “time-bomb under the nation’s finances”.

23

In 2012 the total benefit bill for youth unemployment at its current levels is likely to be just under £4.2 billion, the total cost in taxes foregone is estimated to be over £600 million, and the cost to the economy in terms of lost output is likely to be £10.7 billion.

24

27

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

Beyond material costs, youth unemployment limits social mobility and is disproportionately more likely among ethnic minorities, disabled people and those who have responsibilities as carers.

Unemployment is bad for communities as well as the individuals in those communities who are out of work – evidence shows that it impacts on health outcomes and crime.

25 For businesses, deprivation, crime and poor health make for a challenging environment in which to trade and grow.

On a macroeconomic scale, many businesses have felt that impact since the economic crisis of 2008. On a local scale, businesses that operate in deprived areas face specific challenges. However for that very reason, small steps to address unemployment can have a profound effect.

A retailer who targets the most deprived wards when recruiting in a local area is not only creating jobs, but targeting that job creation where it is most needed – and where it will have the greatest positive impact in terms of the local economy.

Working Links believes that people can turn their lives around if they are given the support they need to find sustainable employment – and we have helped almost a quarter of a million people to do exactly that. Every one of these individual success stories should be cherished. But we also believe that, if helping long-term unemployed people became as common a feature of CR strategies as “saving the planet”, then the benefits to the economy as a whole could be transformational. That was our motivation in commissioning this research and is our call to action for the business community.

At a time when unemployment is high and youth unemployment at record levels, the case for truly responsible businesses to play their part has never been more urgent.

25 lbid

28

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

Section 3:

Employability as CR: the barriers that make it challenging

If employability as CR can be expanded across the

UK many more businesses could replicate the successful employability programmes that remain only a small part of overall CR activity.

29

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

The majority of the employers in our survey have not yet been persuaded of the commercial and reputational benefits of recruiting disadvantaged people.

Working Links is encouraged that those businesses that have recruitment policies in place to help disadvantaged people have seen real commercial and reputational benefits. However, the majority of the employers in our survey have not yet been persuaded of those benefits. Most HR managers (57%) did not have employability schemes and most CR managers (68%) had not considered incorporating them into their wider CR strategies. More worryingly, 73% of CR managers did not think that their company “might benefit from a CR strategy that encourages actively recruiting from disadvantaged groups as a means of tackling unemployment”.

We recognise that businesses have legitimate concerns about implementing employability programmes. Some 55% cited the cost of training as a potential negative, 45% cited concerns over quality of the workforce and 36% cited the cost and time spent recruiting – clearly thinking any policy targeting those furthest from the labour market requires additional effort in finding them in the first place.

HR managers who have actively recruited from disadvantaged groups cited similar issues: 60% raised concerns over quality of the workforce, 58% raised the cost of training and 35% raised the cost and time required to recruit from this group.

A quarter of HR managers (26%) cited legal issues / equality legislation. Working

Links recognises that laws which prevent discrimination on grounds of age inevitably make companies wary of targeting young unemployed people, for example. From the conversations we have had with employers we are aware that concerns around equality legislation are often referenced – in particular the issue of focusing recruitment on a specific age group, such as 18 to 24 year olds. However, we consider that the regulatory obstacles are overstated. Clarity from the government on this issue would be welcome and Working Links endorses the recommendation made in the Riots

Communities and Victims Panel on CR:

“The panel recommends the Government and local authorities should lead by example by publishing their CR commitments, making clear what they are doing to support key

Government initiatives such as the number and type of Apprenticeships offered, work experience opportunities and links to local communities. The Department for Business,

Innovation and Skills should take this forward in their role as CR champion in 2012.” 26

26 Riots, Communities and

Victims Panel (2012)

30

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

One of the biggest issues for recruiters was matching the skills they need from job candidates for employment with the disadvantaged cohort they are targeting.

When asked about “the barriers that you face in actively recruiting from disadvantaged groups”, 70% cited “finding the right skills among people from disadvantaged backgrounds.” They also felt that this group of people might be hard to source (33%) and that, as an employer, it was not always easy to appeal to them (35%). Only 16% said that retaining staff hired from disadvantaged backgrounds was a barrier – evidence which is supported by the improved staff retention cited as a commercial benefit (44%).

We had a range of responses from HR managers who took the opportunity to elaborate on the regulatory barriers. Some cited the necessary checks (for example

Criminal Records Bureau checks) required for their employees to engage in schools.

Others simply said that the red tape and bureaucracy got in the way. A few raised issues about the impact on customers:

“we are in retail and the public do not always respond well to being served by disabled people or ex-cons.” Working Links accepts that such concerns are real, but rejects the premise on which they are made

– it is beyond the scope of this report to champion the rights of disabled people to work, regardless of customers’ perceived prejudices. However, we are an organisation committed to helping disabled people work wherever possible – and overcoming the prejudice that can, at times, prevent them from doing so. Working Links also works with ex-offenders in custody and in the community. Again, this report is not the place to set out the wider societal benefits of assisting ex-offenders into work on release from custody – indeed we have already done so in a research report of 2010, Prejudged: Tagged for Life.

27 But we maintain that overcoming prejudice towards ex-offenders from employers and their customers is in society’s interest.

27 Working Links (2010)

Which groups do you recruit as part of your wider CR?

Young unemployed people

Disabled people

Long-term unemployed people

Ex-offenders

0% 20 40 60 80 100%

31

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

Given the barriers that exist for employers, it is unsurprising that many focus on those disadvantaged people who are easiest to employ. Those CR managers who do recruit from disadvantaged groups are most likely to target young unemployed people – 76% cited this group, 66% cited disabled people and 55% cited long-term unemployed people. For reasons we understand, only

31% focus efforts on ex-offenders. The pattern was similar among HR managers with the majority (81%) citing young unemployed people as a principal target,

60% citing disabled people and 56% citing long-term unemployed people. Fewer HR managers than CR managers (19% as opposed to 31%) cite ex-offenders as a group they would be likely to recruit from.

Working Links has consistently championed the need to address high youth unemployment and we would not want to see efforts in this area to be diminished.

However, employability programmes should not be geared towards younger people at the expense of efforts to support other groups.

Analysis: the barriers that make it harder to recruit from disadvantaged groups

Working Links does not believe that if only businesses could see the benefits of recruiting from disadvantaged groups to their commercial needs, reputation and the wider community, then that cohort could be swiftly and easily employed. The reality is much more complex. We recognise there are barriers and that businesses are not unreasonable in raising concerns about the quality of the workforce, the time and money required for training and recruitment and the potential negativity around recruiting from some groups. We also share the frustration of companies who would consider spending the time and money in recruiting disadvantaged people but are hindered by bureaucracy and unnecessary regulation. However, we do not believe that any of these barriers are insurmountable.

And we think that the necessary steps which businesses might take to address the barriers could deliver rewards that far outweigh the costs. We especially believe that, when the prospects for all business are overshadowed by alarming forecasts of very low or flat growth in the economy, now is the time for proactive solutions.

32

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

What do employers see as the barriers to recruiting people from disadvantaged groups?

70%

Finding people with the right skills

33%

Difficulty in sourcing people

The role of the government

It is clearly in the interest of the UK economy to take steps to reduce unemployment, and so reduce the welfare burden. The proactive recruitment policies we recommend would make a significant contribution to addressing the employability challenges faced by people from disadvantaged groups, and to future economic growth, if widely adopted. It is also in this climate that the reputational benefit of engaging in employability programmes would be most keenly felt. The report After the Riots, commissioned by the government to investigate the causes of the riots in the

UK in August 2011, recommended that more businesses target employability programmes at young people. The report also called on the government to actively support those businesses: “The Panel particularly welcome businesses undertaking corporate social responsibility (CR) activity which supports the local neighbourhoods within which they operate and focuses on using the company brand to engage and work with young people.” The report made the following recommendation: “The Panel encourage more businesses to adopt this model of CR.

The Panel recommends that Government lead by example by publishing its CR offer, including commitments to its key initiatives, for example, number of Apprenticeships and work experience placements.” 28

28 Riots, Communities and

Victims Panel (2012)

35%

Difficulty in making vacancies appeal to people

33

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

Just as the social division brought so vividly to the forefront of politicians’ minds in August last year is a wake-up call to businesses, the urgency of the global economic crisis means that companies which are seen to be tackling it head-on will have a more positive impact on their reputation now than in the good times. In short, now is the time to engage in recruitment solutions which will help disadvantaged people because businesses will achieve maximum impact in terms of reputation and in terms of contributing to economic recovery. If employability as CR can be expanded across the UK, Working Links believes that many more businesses could replicate the successes (as described in the earlier chapters and case studies) that have hitherto only formed a small part of CR activity.

Just as we believe that solutions that will help the economy to recover will be most appealing to customers, we also know that businesses with important government stakeholders have a huge amount to gain. This government, in line with its predecessors, has deployed a range of policies to exhort, incentivise (and in some cases compel) businesses to lead the economy out of recession. In 2012, turning the tide of rising unemployment and youth unemployment is the number one priority for the government.

29 Outside the bounds of this research, Working Links has commended those efforts – especially those efforts that have seen businesses as the solution, not the problem.

The government is keener now than ever before for employers to work with them to reduce unemployment, with recent legislation indicating its willingness to offer advantages to businesses that consider social value in their business operations.

29 5 th January 2012 Deputy

Prime Minister, Rt Hon Nick

Clegg, said “Supporting people into work is my priority for 2012”

34

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

The recently passed Public Services

(Social Value) Act originated as a Private

Members’ Bill introduced by Chris White

MP and received cross-party support.

Its provisions require public bodies to consider the social value of awarding a contract to a provider. Another indication of the cross-party consensus on the importance of this issue was signalled by the Leader of the Opposition in his speech to the Labour Party Conference in 2011.

Ed Miliband suggested that the government should lead the way in placing obligations on elements in the supply chain to play their part in tackling youth unemployment. The

Labour leader pledged that, under a future

Labour government: “all major government contracts will go to firms who commit to training the next generation with decent

Apprenticeships. And none will go to those who don’t”. Working Links believes that any moves that encourage the growth of

Apprenticeships should be welcomed – although we reiterate here our concerns that too few Apprenticeships are going to long-term unemployed people, especially young unemployed people. Last year

Working Links published a research report, Learning a Living, which looked specifically at how the government could ensure better access to Apprenticeships, and we are gratified that a number of our recommendations are now government policy. It is beyond the scope of this document to explore in detail how

Apprenticeships could better help people from disadvantaged groups to find work.

We would, however, recommend that any business considering hiring apprentices take steps to ensure that the lower wages reflected in an Apprenticeship do not present an insurmountable barrier to would-be apprentices from disadvantaged groups.

30 31

Governments, of course, are in a unique position to commission services that are in line with their policies. In practice, this will mean that organisations that choose to employ disadvantaged people as part of their CR could leverage this to give them an advantage over rival providers.

It is beyond the scope of this report to examine the extent to which government could press employability programmes on businesses. However, as the report has previously noted, there is a precedent for those activities that begin life as voluntary

CR policies evolving into mainstream behaviour, before becoming obligations mandated by government. Those businesses which were early adopters of environmentally sustainable practices set the industry standard and so shaped the development of future regulation. The same could happen for businesses that are first to embrace and roll-out employability as a component of CR.

30 Working Links (2011)

31 Business in the

Community (among other organisations) can offer advice to businesses on the specifics of ensuring that Apprenticeships are accessible and financially viable for people from disadvantaged groups http://www.bitc.org.uk/

35

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

Helping people furthest from the labour market

The employment services industry has a strong heritage, with decades of cumulative experience in helping those people furthest from the labour market to find sustainable employment. Providers such as Working

Links work with disabled people, long-term unemployed people and ex-offenders to help them overcome the barriers they face, and to give them the skills and confidence to secure and remain in work. We, and some other providers, also have significant experience of helping young people who are not in education, training or employment to take the steps they need to go on to further training, including Apprenticeships. This experience could readily be used to help those employers who have a stated desire to include employability in their CR strategies to make this a reality, and so help businesses to have that positive impact on society which is valued by their customers and employees, and which will benefit the UK economy.

Key to the kind of employer solutions we deploy is that close partnership with employers. Employers have every right to expect candidates for employment to have the right skills for the job – and our research shows this is a major concern.

Employers are also wary of the bureaucracy that can be involved in employability schemes. An organisation with the skills and experience of Working Links can provide the partnership needed to smooth the way to delivering a reliable stream of work-ready employees with minimum paperwork. We can also source the potential employees from disadvantaged groups. Indeed, in deprived areas, we work right in the heart of communities to build close and trusting relationships with disadvantaged people.

Alongside specialist employment providers, employers in the UK are fortunate enough to draw on the passion and expertise of large numbers of small and medium-sized voluntary organisations equally committed to helping people with disadvantages into work. BITC’s excellent work in this area has already been flagged in this report – their Ready for Work programme being a fine example of how the voluntary sector can work with employers. The government also recognises the vital role of the voluntary sector, and drawing on its experience and talent is critical to the delivery of the Work Programme. Working

Links is proud of its own partnerships with such organisations as The Prince’s

Trust, Gingerbread and Shaw Trust.

However, overcoming these barriers is not the sole responsibility of employment solutions providers or the voluntary sector.

In return for the business benefits of proactively recruiting from disadvantaged groups, employers must agree set targets and set attainment levels. In our experience, it is the prospect of a lasting job that most motivates long-term unemployed people

– especially young people – to engage in the sorts of programmes we run. As valuable as employability training, CV writing and interview practices are, they are far more attractive if the customer sees the final destination as a real job.

We believe our innovative solutions offer the means to achieve these outcomes.

Working Links recognises – and our research reflects this – that it remains our challenge to persuade employers of this argument.

We found that 65% of HR managers did not partner with outside organisations to help them in delivering support or employment to disadvantaged groups. And 57% of HR managers said that they would not consider partnering with services which support disadvantaged people into employment. By a small margin, a majority of HR managers

(56%) thought that they could benefit from working in partnership if they chose to do so – but most, as we have seen, would not consider it in the first place.

36

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

What are the main challenges you face when recruiting from disadvantaged groups?

Concerns over the quality of the workforce

Cost of training

Cost and time spent recruiting

Legal issues / equality legislation

0% 20 40 60 80 100%

If the challenge of supporting people into employment is to fall to business, then the challenge of making it straightforward and beneficial should not fall to businesses alone.

In partnership with government, training providers and welfare to work providers,

Working Links is piloting and delivering the solutions that will remove the barriers and help businesses to successfully recruit from among disadvantaged groups.

A more recent obstacle that could inhibit an organisation’s enthusiasm for employability programmes has been the negative publicity surrounding some government employment schemes, including schemes that offer unpaid work experience. It would be tragic for the cause of employability programmes if businesses were to assess that the reputational risk of engaging in them outweighed the societal and business benefits – and this has happened with some large national employers. Working closely with governments to deliver programmes aimed at addressing societal problems is not risk-free. For some, the very notion of the government outsourcing core functions, such as providing welfare, has made providers a target. In other cases, being associated with schemes that are closely linked to one political party or government can leave an organisation exposed if that policy, or the political party sponsoring it, becomes unpopular. Employability schemes must, therefore, be designed and stress-tested to ensure that their noble intentions can be credibly delivered – the reputational damage of claiming to help people and being found wanting is greater than doing nothing at all. The government also has a responsibility to ensure that its programmes, which will always depend on employers, will not reflect badly on those organisations that choose to embrace them.

37

The Responsible Employer: Employability as a component of Corporate Responsibility

Employability as CR: large employers

Working Links believes that large employers have a vital role to play in helping to address high levels of unemployment and youth unemployment.

We also believe that large employers who opt to channel their work around CR into employability schemes will benefit commercially, and in terms of the impact of their CR work on their reputation. The strongest evidence for this is the existing high level of engagement by large firms in such schemes already.

In January 2012, the Deputy Prime Minister brought together a number of large employers to promote the government’s