Volume 18, Number 7 Printed ISSN: 1078

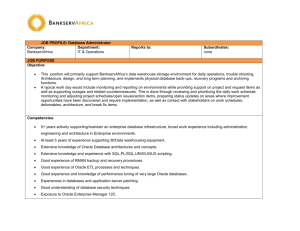

advertisement