Reducing Fear of Crime: Strategies for Police

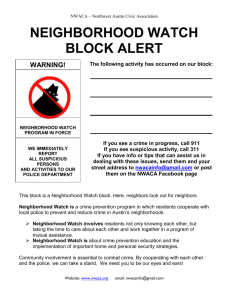

advertisement