Will the FTC's Advisory Opinion on the Holder in Due Course Rule

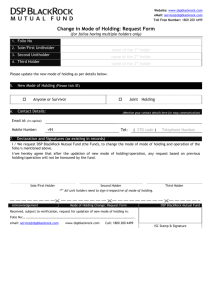

advertisement

Will the FTC’s Advisory Opinion on the Holder in Due Course Rule Change the Treatment of Claims Against Assignees? By John L. Ropiequet1 In May 2012, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) issued a formal advisory opinion (Advisory Opinion)2 which stated that consumers who seek affirmative relief against assignees of their contracts under the Holder in Due Course Rule (Holder Rule)3 are not limited to claims that the goods or services they purchased are so worthless that the transaction can be rescinded. The Advisory Opinion was issued in response to a letter from consumer advocacy groups which asserted that numerous courts had misinterpreted the Holder Rule over the years by limiting its application to cases in which the consumer was justified in seeking rescission of the contract. The Holder Rule was promulgated by the FTC in 1975.4 The Rule provides that persons who “[t]ake or receive a consumer credit contract” in which the following language is missing are guilty of an unfair practice that violates Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act:5 NOTICE ANY HOLDER OF THIS CONSUMER CREDIT CONTRACT IS SUBJECT TO ALL CLAIMS AND DEFENSES WHICH THE DEBTOR COULD ASSERT AGAINST THE SELLER OF GOODS OR SERVICES OBTAINED PURSUANT HERETO OR WITH THE PROCEEDS HEREOF. RECOVERY HEREUNDER BY THE DEBTOR SHALL NOT EXCEED AMOUNTS PAID BY THE DEBTOR HEREUNDER.6 John L. Ropiequet is counsel to Arnstein & Lehr LLP, Chicago, where he has practiced for over thirty years and is cochair of its Consumer Finance Group. He may be contacted at (312) 876-7814 or jlropiequet@arnstein.com. 16 • Banking & Financial Services Policy Report The FTC issued an explanatory Statement of Basis and Purpose (SBP) along with the Holder Rule. The following statement was included in the SBP: This rule is directed at the preservation of consumer claims and defenses [which] means that a consumer can (1) defend a creditor’s suit for payment of an obligation by raising a valid claim against the seller as a set off, and (2) maintain an affirmative action against a creditor who has received payments for return of monies paid on account. The latter alternative will only be available when the seller’s breach is so substantial that a court is persuaded that rescission and restitution are justified. The most typical example is such a case would involve non-delivery, or delivery was scheduled after the date payments to a creditor commenced.7 If the Holder Rule language is read literally, it would seemingly mean that any type of claim that a purchaser under the retail installment contract might have against the seller could also be brought against any person to whom the contract is assigned because the language of the contract provides for such liability. Court rulings, which have relied on the above language of the SBP have, however, significantly restricted assignee liability. This caused one of the same consumer advocacy groups that influenced the FTC to issue the Advisory Opinion to take issue with these interpretations several years earlier. In response to the group’s concerns, the FTC’s staff issued an opinion letter in 1999 (Staff Letter),8 which took issue with those decisions. The Advisory Opinion stated that the “plain language” of the Holder Rule, making every holder of a consumer credit contract “subject to all claims and defenses which the debtor could assert against the seller of goods or services,” does not limit the consumer to use of the Holder Rule as a defense to a creditor’s claims for the contract balance.9 The Opinion stated Volume 32 • Number 9 • September 2013 that the Holder Rule also permits the consumers to make affirmative claims for relief even if “rescission is not warranted.”10 The Opinion further noted that assignee liability for affirmative claims is limited to the amounts paid on the contract prior to suit by the consumer.11 Assignee Claims under the Truth in Lending Act and the Holder Rule After a number of early cases under the Truth in Lending Act (TILA)12 failed to distinguish between the original creditors on credit sale contracts and their assignees, TILA was amended in 1980 to clarify that contract assignees are not to be treated the same as the creditors who first extend credit to consumers. The amended definition of “creditor” was The term “creditor” refers only to a person who both (1) regularly extends, whether in connection with loans, sales of property or services, or otherwise, consumer credit which is payable by agreement in more than four installments and for which the payment of a finance charge is or may be required, and (2) is the person to whom the debt arising from the consumer credit transaction is initially payable on the face of the evidence of indebtedness or, if there is no such evidence of indebtedness, by agreement … .13 To go with this new definition, a limitation on the liability of contract assignees was also added to TILA in Section 1641(a): Except as otherwise specifically provided in this subchapter, any civil action for a violation of this subchapter or proceeding under section 1607 of this title which may be brought against a creditor may be maintained against any assignee of such creditor only if the violation for which such action or proceeding is brought is apparent on the face of the disclosure statement except where the assignment was involuntary … .14 The difference between a “creditor” and an “assignee” in connection with the Holder Rule became the subject of definitive court rulings in 1998.15 In one case, Taylor v. Quality Hyundai, Inc.,16 the Seventh Circuit held that the Holder Rule language (Holder Notice) could not be allowed to override the limitation Volume 32 • Number 9 • September 2013 on assignee liability enacted by Congress in the TILA amendments: The plaintiffs initially argued that the TILA actually has nothing to do with the assignee’s liability in these cases, because they are bound under the terms of the contracts they accepted, wholly apart from the statute … . In our view, however, this misconstrues the effect of the Holder Notice insofar as it covers TILA-based claims. * * * The Holder Notice, even though contained within the contract, was not the subject of bargaining between the parties and indeed could not have been. It is part of the contract by force of law, and it must be read in light of other laws that modify its reach. [citation omitted] We therefore reject the plaintiffs’ contract-based effort to sidestep [section] 1641(a).17 This holding was confirmed by the Seventh Circuit in Walker v. Wallace Auto Sales, Inc.18 The Walker court held that “the FTC’s Holder Notice in a retail installment contract did not trump the clear command of section 131 [of TILA] that subsequent assignees can be held liable under TILA only when the violation is apparent on the face of the disclosure statement.”19 These rulings were followed by several others in short order.20 The Seventh Circuit did not find that the limitation on assignee liability in TILA simply nullified the Holder Rule language, however. Relying on earlier cases that dealt with the issue, the court found that the Holder Rule would be given effect in circumstances in which the consumer is entitled to rescind the contract, allowing the contract to be rescinded against both the original creditor and any assignee of the contract if rescission were justified.21 The court cited a district court opinion in Mount v. LaSalle Bank Lakeview,22 which held that the Holder Rule permits a consumer to sue a creditor to obtain a refund of all money that has been paid on a contract, limited to cases in which “the seller’s breach was so substantial that rescission and restitution were justified under equitable state law principles.”23 Mount and the cases it relied on, particularly the decision of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Banking & Financial Services Policy Report • 17 Court in Ford Motor Credit Co. v. Morgan,24 cited and relied on the comments in the SBP quoted above.25 Following the issuance of the Taylor and Walker decisions, and other cases following them,26 only one federal case has dissented from the proposition that assignee liability under the Holder Rule is limited to situations in which the consumer is entitled to rescind. In that case, Lozada v. Dale Baker Oldsmobile, Inc.,27 the court conceded that Taylor would not permit a TILA claim to be brought against an assignee absent rescission, but it held that the plaintiff could still, under a state uniform deceptive acts and practices (UDAP) statute, bring claims that were based on a TILA violation against an assignee pursuant to the Holder Rule.28 This ruling was not appealed, but Lozada was subsequently overruled by the Sixth Circuit on other grounds.29 State Law Holder Rule Claims Against Assignees Prior to the Taylor and Walker decisions, several courts applied the Holder Rule to hold assignees of consumer credit contracts liable for state law claims against the original creditors. One case which is frequently cited by the plaintiff’s bar is Eachen v. Scott Housing Systems, Inc.30 The plaintiff mobile home buyers in Eachen were able to sue both the manufacturer of their mobile home and the finance company which financed their purchase when it bought their contract from a mobile home dealer for breach of warranty.31 Several similar rulings which applied the Holder Rule literally were made in other cases prior to 1998.32 Other cases took a different approach by examining both the Holder Rule and the SBP, finding that the FTC did not intend that assignees could be held liable for any claim against the original creditor. The leading case was the Morgan decision. In that case, the court dealt with claims which car buyers brought against Ford Motor Credit as the assignee of their retail installment contract with the dealer who sold them the car. They asserted that the finance company was liable for their claims of fraud, deceptive practices, and breach of warranty against the dealer.33 The Morgan court found that although the Holder Rule was intended to preserve a consumer’s defenses to further payment on a contract in cases in which the issuer of the contract is guilty of wrongdoing, the FTC 18 • Banking & Financial Services Policy Report “anticipated that in addition to non-payment, affirmative recovery, that is, a judgment for damages against the assignee-creditor, would be available in limited circumstances.”34 It found that pursuant to the language in the SBP, those circumstances were limited to cases in which “a seller’s breach is so substantial that a court is persuaded that rescission and restitution are justified.”35 The Morgan court further noted that the FTC reemphasized this in the SBP by stating that Consumers will not be in a position to obtain an affirmative recovery from a creditor, unless they have actually commenced payments and received little or nothing of value from the seller. In a case of non-delivery, total failure of performance, or the like, we believe the consumer is entitled to a refund of monies paid on the account.36 The court found that the plaintiffs’ claim was not preserved by the Holder Rule because they made no claim of entitlement to rescission and restitution.37 The 1999 Staff Letter stated that Morgan and the cases which followed it38 erred by “interpreting the provision to allow a consumer an affirmative recovery only if he or she is entitled to rescission or similar relief under state law, [and] are inconsistent with our position.”39 It also stated that We believe that the point made in these SBP excerpts is simply that affirmative recoveries will be rare because they occur only if … the consumer has a claim large enough to more than extinguish the balance due. If the Commission had meant to limit the recovery to claims subject to “rescission” or similar remedy, it would have said so in the text of the Rule and drafted the contractual provision accordingly.40 The Staff Letter concluded with a disclaimer that “[t]he views set forth in this informal staff opinion letter are not binding on the Commission.”41 The Letter made no mention of then-recent decisions by the Seventh Circuit in Taylor and Walker with respect to application of the Holder Rule to TILA claims. The Staff Letter was either ignored in subsequent case decisions or was given little weight. In the leading decision of Jackson v. South Holland Dodge, Inc.,42 Volume 32 • Number 9 • September 2013 which came down in 2001, two years after the Staff Letter was issued, the Illinois Supreme Court dealt with a case in which the plaintiff brought an action under the Illinois Consumer Fraud Act (ICFA),43 a UDAP statute, against the finance company which took assignment of his retail installment contract from the dealer. The ICFA claims were based on the dealer’s failures to make credit disclosures which were required by TILA and other allegedly deceptive practices.44 The Jackson court ruled that the limitation on assignee liability in TILA, Section 1641(a), could not be circumvented by making a claim under the ICFA for consumer fraud because allowing such a claim “would frustrate the overarching reasons put forth by Congress in enacting the assignee exemption.”45 The court further rejected the argument that the Holder Rule language in the contract meant that the assignee assumed liability for wrongdoing by the dealer as a matter of state contract law, following Taylor, because the contract language was there by virtue of the FTC’s regulation instead of being part of the parties’ bargain, and because the 1975 Holder Rule was trumped by the 1980 amendments to TILA.46 The court also noted the limitation of claims against assignees to situations in which “rescission and restitution are justified” in the SBP, which was the “official FTC commentary on the subject.”47 The court found that the Staff Letter was an attempt to “contradict the official commentary” in the SBP, but since it was an “informal staff opinion letter, not binding on the FTC,” it was not “persuasive authority to override the official commentary.”48 Most cases which have come down after Jackson have reached the same result. One which reached a different result, Scott v. Mayflower Home Improvement Corp.,49 which found that claims under the New Jersey UDAP statute were preserved by the Holder Rule and were not subject to the limitation on assignee liability in Section 1641(a),50 was subsequently overruled in Psensky v. American Honda Finance Corp.,51 which followed Jackson.52 The Advisory Opinion The consumer advocates’ letter to which the Advisory Opinion responded listed six cases in which the courts had imposed a rescission requirement to limit the scope of the Holder Rule.53 The Opinion seemed to consider these cases to be rogue decisions, and it took the position that the “plain language” of Volume 32 • Number 9 • September 2013 the Holder Rule does not limit a consumer to mere defensive use of the Holder Rule against claims for the balance owed on the contract.54 Instead, the Opinion stated that the contract language, which the Holder Rule requires in consumer credit contracts, “protects consumers who enter into credit contracts with a seller of goods or services by preserving their right to assert claims or defenses against any holder of the contract, even if the original seller subsequently assigns the contract to a third-party creditor,” limited only by the provision “that a consumer’s recovery ‘shall not exceed amounts paid’ by the consumer under the contract.”55 The Advisory Opinion stated that Morgan was wrongly decided because “the Rule is unambiguous, and its plain language should be applied” since no rescission limitation was made a part of the Holder Rule, and if the FTC had intended there to be such a limitation, “it would have said so in the text of the Rule and drafted the contractual provision accordingly.”56 The Opinion noted that when the FTC promulgated the Holder Rule, it rejected suggestions from the industry that the Rule be limited to matters of defense or setoff, and that “to give full effect to the Commission’s original intent to shift seller misconduct costs away from consumers,” consumers must be able to recover all of the funds they have paid “even if rescission is not warranted.”57 Rather than attempt to amend or withdraw the statements in the SBP that the Morgan court and other courts have relied on, the Advisory Opinion simply stated that those were “two isolated comments in the SBP” which had been misinterpreted.58 In order to place the comments “in the context of the entire SBP,” the FTC approved how the Lozada court handled the SBP comments: [W]hen read in context of the entire SBP, including the SBP language highlighted above, two SBP comments cited by Morgan and its progeny do not undermine the plain language of the Rule. As explained by one court that rejected the Morgan approach, “[w]here one or more parts of the [SBP] fully comport with the text of the Rule while another, read in a particular way, is at odds with the plain language of the regulation, there exists no basis for giving controlling weight to an interpretation of the rule itself.” These statements Banking & Financial Services Policy Report • 19 should be read as practical observations or predictions, instead of as contradicting the Rule.59 law claims are based on alleged TILA violations for the reasons stated in Jackson.66 The Advisory Opinion found that this interpretation was appropriate because most of the time, if there is a “significant consumer injury” that does not warrant rescission, “the consumer is likely to find out about the injury shortly after the transaction is consummated, and thus is likely to stop payments before the claim amount is larger than the balance due.”60 The Advisory Opinion concluded that the SBP comments “do not conflict with the rest of the SBP and the plain language of the Rule” because “affirmative recoveries will be rare in cases where rescission is not justified because such recoveries occur only if the consumer’s claim is larger than what the consumer still owes on the loan.”61 The result may be different if the consumer brings a state law claim that is not based on a TILA violation, for example, a UDAP claim for fraud by an auto dealer rather than improper credit disclosures. In such cases, in jurisdictions where the reported decisions have followed Morgan, the plaintiff will have to persuade the courts that the Advisory Opinion merits a new look at the question and a change in the law. The Advisory Opinion has caused at least one court to decline to follow cases in other jurisdictions which have imposed a rescission requirement where there was no previous case law in the state which had followed Morgan.67 Where there is decisional law that imposes such a limitation on the Holder Rule, it may take some time before the courts accept the Advisory Opinion as a proper basis for overruling established case law that imposes a rescindability requirement on claims against assignees. Conclusion The plaintiff’s bar has expressed a readiness to use the Holder Rule as a basis for making claims against both original creditors and assignees.62 The Advisory Opinion strengthens their case, particularly in cases in which the courts may have found that the Staff Letter should be given little weight because it was not an official pronouncement of the FTC.63 The Advisory Opinion, which was approved by a unanimous vote by the FTC,64 demonstrates that the full Commission, not just its staff, stands behind the proposition that affirmative relief under the Holder Rule is not limited to situations in which rescission and restitution are justified. Although the Advisory Opinion took on the 1989 Morgan decision directly, it was totally silent on the 1998 Taylor and Walker decisions which held that the congressional amendments to TILA in 1980 trump the FTC’s Holder Rule with respect to TILA-based claims. Nor did it address the 2001 Jackson decision or cases following Jackson which held that the TILA limitation on assignee liability cannot be circumvented by using an alleged TILA violation by the original creditor as the basis for a UDAP claim against an assignee. The Advisory Opinion is unlikely to sway courts in cases in which TILA disclosure violations form the basis for claims, given the uniform position taken by numerous federal courts which have followed Taylor and Walker.65 The result will likely be the same if state 20 • Banking & Financial Services Policy Report Notes 1. The author represented defendants in the following cases mentioned in this article: Walker v. Wallace Auto Sales, Inc., 155 F.3d 927 (7th Cir. 1998); Balderos v. City Chevrolet, Buick & Geo, Inc., 214 F.3d 849, 853 (7th Cir. 2000); Irby-Greene v. M.O.R., Inc., 79 F. Supp. 2d 630, 633-34 (E.D.Va. 2000); Knapp v. AmeriCredit Fin. Serv., Inc., 245 F. Supp. 2d 841, 848 (S.D.W.Va. 2003). 2. Letter from Donald S. Clark, Secretary, FTC, to Jonathan Sheldon, et al., National Consumer Law Center (May 3, 2012) [hereinafter Advisory Opinion], available at http://ftc.gov/os/2 012/05/120510advisoryopinionholderrule.pdf. See Press Release, Fed. Trade Comm’n, FTC Opinion Letter Affirms Consumers’ Rights under the Holder Rule (May 10, 2012), available at http://ftc.gov/opa/2012/05/holderrule.shtm. 3. 16 C.F.R. pt.433 (2012). 4. 40 Fed. Reg. 53506 (Nov. 18, 1975). 5. 15 U.S.C. § 45 (2006). 6. 16 C.F.R. § 433.2(a) (2012). 7. 40 Fed. Reg. at 53524 (emphasis supplied). 8. Letter from David Medine, Associate Director, Division of Financial Practices, FTC, to Jonathan Sheldon, National Consumer Law Center (Sept. 25, 1999) [hereinafter Staff Letter], available at http://ftc.gov/os/2012/05/120510staffletter1999.pdf. 9. Advisory Opinion, supra n.2, at 2, 4. 10. Id. at 4. 11. Id. 12. Pub. L. No. 90-321, 82 Stat. 146 (1968) (codified as amended at 15 U.S.C. §§ 1601–1667f (2006 & Supp. V 2011)). Volume 32 • Number 9 • September 2013 13. 15 U.S.C. § 1602(f) (2006) (emphasis supplied). Regulation Z was similarly amended. 12 C.F.R. § 1026.2(a)(17) (2012). 14. 15 U.S.C. § 1641(a) (2006) (emphasis supplied). 15. See generally Mark A. Dapier, Eugene J. Kelley, Jr., John L. Ropiequet & Christopher S. Naveja, “Assignee Liability Under the TILA: Is the Conduit Theory Really Dead?” 54 Consumer Fin. L.Q. Rep. 242 (2000), reprinted in Ralph J. Rohner & Fred H. Miller, Truth in Lending ¶ 12.06[1] (2d ed. 2000 & Supp. 2009). Co. v. Stamatiou, 384 So. 2d 388 (La. 1980); Thomas v. Ford Motor Credit Co., 48 Md. App. 617, 429 A.2d 277 (1981); Hardeman v. Wheels, Inc., 56 Ohio App. 3d 142, 565 N.E.2d 849 (1988). 33. Morgan, 404 Mass. at 539-540. 34. Id. at 541-542 & n.2. 35. Id. (citing SBP, 40 Fed. Reg. at 53524). 36. Id. at 542 (citing SBP, 40 Fed. Reg. at 53527) (emphasis supplied). 16. 150 F.3d 689 (7th Cir. 1998), cert. denied, 525 U.S. 1141 (1999). 37. Id. at 543. 17. Id. at 693. 38. See Staff Letter, supra n.8, at 2, n.3 (citing Mount v. LaSalle Bank Lakeview, 926 F. Supp. 759, 763-764 (N.D. Ill. 1996); In re Hillsborough Holdings Corp., 146 B.R. 1015, 1021 (Bankr. M.D. Fla. 1992); Felde v. Chrysler Credit Corp., 219 Ill. App. 3d 530, 580 N.E.2d 191, 197 (1991); Mardis v. Ford Motor Credit Co., 642 So. 2d 701, 703 (Ala. 1994)). 18. 155 F.3d 927 (7th Cir. 1998). 19. Id. at 935 (citing 15 U.S.C. § 1641(a)). This holding was reaffirmed in Balderos v. City Chevrolet, Buick & Geo, Inc., 214 F.3d 849, 853 (7th Cir. 2000). 20. See Ramadan v. Chase Manhattan, 229 F.3d 194, 198 (3d Cir. 2000); Green v. Levis Motors, Inc., 179 F.3d 286, 295 (5th Cir.), cert denied, 520 U.S. 1020 (1999); Ellis v. Gen. Motors Acceptance Corp., 160 F.3d 703, 709 (11th Cir. 1998); IrbyGreene v. M.O.R., Inc., 79 F. Supp. 2d 630, 633-34 (E.D. Va. 2000); Knapp v. AmeriCredit Fin. Serv., Inc., 245 F. Supp. 2d 841, 848 (S.D.W. Va. 2003); Van Vels v. Premier Athletic Center of Plainfield, Inc., 1998 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 10993 (W.D. Mich. 1998); Coleman v. Gen. Motors Acceptance Corp., 196 F.R.D. 315 (N.D. Tenn. 2000). 42. 197 Ill. 2d 39, 755 N.E.2d 462 (2001). See generally Assignee Liability, supra n.28. 21. Walker, 150 F.3d at 693. 46. Id. at 53-54 (citing Taylor, 150 F.3d at 693). 22. 926 F. Supp. 759 (N.D. Ill. 1996). 47. Id. at 54-55 (citing SBP, 40 Fed. Reg. at 53524). 23. Id. at 763-764 (citing Felde v. Chrysler Credit Corp., 219 Ill. App. 3d 530, 536, 580 N.E.2d 191, 196 (1991); Ford Motor Credit Co. v. Morgan, 404 Mass. 537, 541-542, 536 N.E.2d 587, 589-590 (1989)). 49. 363 N.J. Super. 145, 831 A.2d 564 (2001). 24. 404 Mass. 537, 541-542, 536 N.E.2d 587, 589-590 (1989). 25. Mount, 926 F. Supp. at 763-764. 39. Id. at 1-2. 40. Id. at 2. 41. Id. 43. 815 ILCS 505/2 (2010). 44. 197 Ill. 2d at 41-42. 45. Id. at 49-50. 48. Id. at 55. 50. 363 N.J. Super. at 155-56, 831 A.2d at 570 (following Lozada and rejecting Taylor line of cases). 51. 378 N.J. Super. 221, 875 A.2d 290 (2005). 26. See supra ns.19-20. 52. Id. at 231, 875 A.2d at 296 (citing Jackson, 755 N.E.2d at 469). 27. 91 F. Supp. 2d 1087 (W.D. Mich. 2000). 53. See Advisory Opinion, supra n.2, at 1 n.3 (citing Rollins v. Drive-1 of Norfolk, Inc., No. 2:06-cv-375, 2007 WL 602089 (E.D. Va. Feb. 21, 2007); Phillips v. Lithia Motors, Inc., No. 03-cv-3109-HO, 2006 WL 1113608 (D. Ore. Apr. 27, 2006); Costa v. Mauro Chevrolet, Inc., 390 F. Supp. 2d 720 (N.D. Ill. 2005); Comer v. Person Auto Sales, Inc., 368 F. Supp. 2d 478 (M.D.N.C. 2005); Herrara v. North & Kimball Group, Inc., No. 01-cv-7349, 2002 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 2640 (N.D. Ill. Feb. 15, 2002); Bellik v. Bank of Am., 373 Ill. App. 3d 1059, 869 N.E.2d 1179 (2007)). Like the Jackson court, the Comer court was cited “as pointedly rejecting the FTC staff opinion letter … [as] ‘not binding on the Commission.’” Id. 28. Id. at 1098 n.2 (citing Pawlikowski v. Toyota Motor Credit Corp., 309 Ill. App. 3d 550, 722 N.E.2d 767, 773 (1999)). Pawlikowski was subsequently overruled in Jackson v. South Holland Dodge, Inc., 197 Ill. 2d 39, 755 N.E.2d 462 (2001). See generally Eugene J. Kelley, Jr. & John L. Ropiequet, Assignee Liability Under State Law after Jackson v. South Holland Dodge, 56 Consumer Fin. L.Q. Rep. 16 (2002), reprinted in Ralph J. Rohner & Fred H. Miller, Truth in Lending ¶ 12.06[5] (2d ed. 2000 & Supp. 2009) [hereinafter Assignee Liability]. 29. See Baker v. Sunny Chevrolet, Inc., 349 F.3d 862 (6th Cir. 2003). See also Dykstra v. Wayland Ford, Inc., 134 Fed. App’x 911 (6th Cir. 2005). 30. 630 F. Supp. 162 (M.D. Ala. 1986). 31. Id. at 164-165. 32. See, e.g., Perry v. Household Retail Serv., Inc., 953 F. Supp. 1370, 1375-1376 (M.D. Ala. 1996); Mayberry v. Said, 911 F. Supp. 1393, 1402-1403 (D. Kan. 1995); Cox v. First Nat’l Bank of Cincinnati, 633 F. Supp. 236, 239 (S.D. Ohio 1986); Bendix Home Sys., Inc., 644 P.2d 843 (Alaska 1982); Jefferson Bank & Trust Volume 32 • Number 9 • September 2013 54. Advisory Opinion, supra n.2, at 1 & n.2. 55. Id. at 2. 56. Id. at 3. 57. Id. at 3-4. 58. Id. at 4. 59. Id. at 4-5 (citing Lozada, 91 F. Supp. 2d at 1096). The Advisory Opinion did not note that Lozada had been overruled and likewise did not note that the Scott decision in New Jersey, which Banking & Financial Services Policy Report • 21 it cited as one of the “many cases” which followed the interpretation of the Holder Rule in the Staff Letter, had also been overruled. See id. at 3 & n.7. Two other cases it cited, Simpson v. Anthony Auto Sales, Inc., 32 F. Supp. 2d 405, 409 n.10 (W.D. La. 1998), and Riggs v. Anthony Auto Sales, 32 F. Supp. 2d 411, 416 n.13 (W.D. La. 1998), were decided about three weeks after the Taylor decision came down and did not mention or consider the Taylor decision. 60. Advisory Opinion, supra n.2, at 5. cases which interpret the Holder Rule as requiring entitlement to rescission for claims for affirmative relief represent the “minority view.” See id. at 363-364. See generally Nat’l Consumer Law Center, Unfair and Deceptive Acts and Practices § 6.6 (6th ed. 2004). 63. See, e.g., Jackson, 197 Ill. 2d at 55. 64. See Press Release, supra n.2. 65. See supra ns.19-20. 61. Id. 66. See supra text at ns.42-48. See generally Assignee Liability, supra n.28, at 22. 62. See, e.g., David A. Szwak, “The FTC ‘Holder’ Rule,” 60 Consumer Fin. L.Q. Rep. 361 (2006). The author takes the position that the 67. Lafferty v. Wells Fargo Bank, 213 Cal. App. 4th 545, 559-563, 153 Cal. Rptr. 3d 240, 250-253 (2013). 22 • Banking & Financial Services Policy Report Volume 32 • Number 9 • September 2013