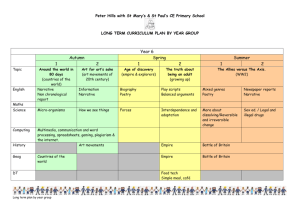

CONTENTS: Food and Nutrition

advertisement