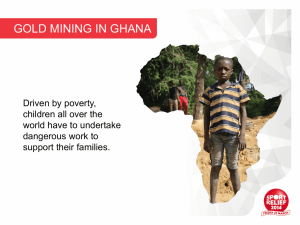

Ghana country case study

advertisement