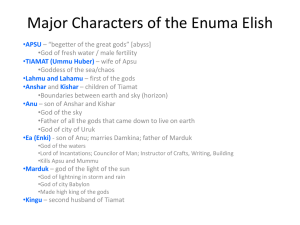

Creation in the Ancient Near East

advertisement