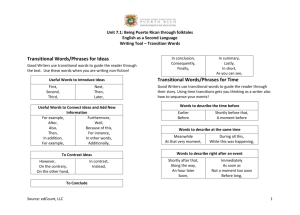

Language Arts - Portland Public Schools

advertisement