Linguistics of White Racism

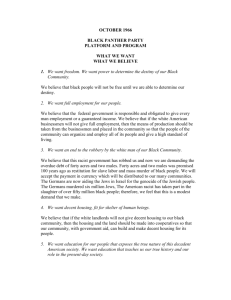

advertisement