Bacon's Rebellion & Transformation of American Slavery

advertisement

Bacon’s Rebellion and the

Transformation of American

Slavery

By: Matthew J. Zaros

St. Bonaventure University

Thesis Mentor: Dr. Karen E. Robbins

1

Historiography

When Nathanial Bacon formed together his rag tag army of poor whites and enslaved

Africans in the late 17th century he had no idea what the ramifications would be for Virginia’s

society. It was Bacon’s original goal to eradicate the Indians from Virginia, but as events

unfolded his rebellion turned into an uprising of the poor against the rich. Although Bacon

ultimately failed, his actions caused a paradigm shift in the thinking of the ruling class of

Virginia, whom the Historian Edmund S. Morgan calls the “labor barons.”1 They controlled the

largest plantations in Virginia and most of the wealth. The labor barons became afraid of another

uprising of poor whites and enslaved Africans. In response to their fear the labor barons created a

more brutal and oppressive system of slavery. They enacted new laws and practices separating

the whites from the blacks. These new laws and practices formed after Bacon’s Rebellion shaped

slavery and race relations in Virginia, and then eventually the colonies, for centuries to come.

Bacon’s Rebellion was looked upon by early historians as a prelude to the American

Revolution. The rebellion was depicted as rugged frontiersmen taking on the English elite for

freedom and rights. But in the 1950’s Wilcomb Washburn wrote, The Governor and the Rebel.

Washburn took a new look at Bacon, trying to decipher what kind of man he really was. He

eventually discovered that Bacon was not the bringer of freedom as early historians once

thought. Bacon’s true intention was not liberation but slaughter. Washburn writes, “He

(Governor Berkeley) refused to authorize the slaughter and dispossession of the innocent as well

as the guilty.”2 He argued Bacon’s true intention was to gain more land by taking it from the

1

Edmund S. Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia (New

York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc, 2005) 269.

Wilcomb E. Washburn, The Governor and The Rebel: A History of Bacon’s Rebellion in Virginia

(Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 1957) 163.

2

2

Indians. When Governor Berkeley tried to stop Bacon, Bacon’s army marched towards

Jamestown. Bacon was fighting this war for his own self-interest and not for any kind of

romanticized freedom.3

It should be noted that Governor Berkeley was not a saint in this matter. He did not have

the best interest of the Native Americans or his people at heart. Berkeley and his friends had a

large stake in the Indian fur trade. Good relations with the Native Americans meant that more of

the lucrative furs would be lining Berkeley’s pockets. But unbeknownst to Bacon and Berkeley

their decisions during the rebellion would be a watershed moment for slavery for hundreds years

to come.4

After the civil rights movement of the 1960 slavery and Bacon’s Rebellion were

reviewed by the historian Edmund S. Morgan. Morgan in his journal article titled Slavery and

Freedom: The American Paradox discusses how historians needed to start examining slavery

with a finer toothed comb. The American Paradox was the fact that some of our most influential

founding fathers were slave owners. The founding fathers fought a rebellion for freedom, yet

they were personally enslaving hundreds of men. Morgan believed that the key to understanding

slavery was Virginia, because it was there that the American Paradox was born. The Paradox

was especially directed towards Patrick Henry, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and

James Madison, who were thought to be these moral men and bringers of freedom, yet were

James D. Rice, Tales From a Revolution: Bacon’s Rebellion and the Transformation of Early

America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012) 205.

3

4

Rice, Tales From A Revolution, 204-5; Alan Taylor, American Colonies: The Settling of North

America (New York: Penguin Books, 2001) 144-50.

3

perpetrators of a brutal slave system in Virginia. Morgan states, “To a very large degree it may

be said that Americans bought their independence with slave labor.”5

Because Virginia was so influential in the revolution Morgan believed that it would also

hold the key to the origins of slavery. In American Slavery, American Freedom he argues that

Bacon’s Rebellion was that key moment in Virginia’s history. Morgan found that Bacon’s

Rebellion had three ramifications on Virginia’s society: It pushed it more towards slavery, more

towards racism, and more towards populism for the whites. Essentially the labor barons after

Bacon’s Rebellion started to import more slaves than indentured servants and passed laws

discriminating against blacks. At the same time they also gave poor whites more freedom.

Because of this, resentment between the poor whites and the blacks grew. This reassured the

labor barons that another Bacon could not come along and unite the white poor and enslaved

Africans in rebellion. Morgan’s research was fundamental in establishing a timeline of events

for how Bacon’s Rebellion changed Virginia’s culture.6

Morgan did a masterful job of mapping out the cause and effects of Bacon’s Rebellion.

Any book on early Virginia worth its weight in salt will have Morgan cited. But he lacked detail

on how vastly different slavery was before Bacon’s Rebellion. Writing in the 1980’s T.H. Breen

and Stephen Innes filled that void with “Myne Owne Ground.” Breen and Innes argue that

Africans before Bacon’s Rebellion had more rights and greater freedoms than their counter parts

in later centuries. They found that slaves could work towards their own freedom and once free

they faced little discrimination. The book focused on the lives of many different free and

enslaved Africans from 1619 to 1676. Their research relied heavily on Anthony Johnson, a

Edmund S. Morgan, “Slavery and Freedom: The American Paradox,” The Journal of American

History 59 (1972) 6; 1-77; Rice, Tales From a Revolution, 205-6.

5

6

Morgan, American Slavery, 296, 316-319, 338-341.

4

former slave who was able to purchase his own freedom. Johnson moved up the social later to

become one of Virginia’s top planters. Virginia had a fairly large free African community. After

Bacon’s Rebellion the free African communities were devastated by extreme racism and

brutality, thus they died out.7

Breen’s, Innes’ and Morgan’s work was eventually continued by Ira Berlin in the 1990’s.

Berlin took nothing away from Morgan, Breen or Innes, all he did was add some color

commentary. In his book Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North

America Berlin fills in the details of what slavery was like before and after Bacon’s Rebellion.

He called the society before Bacon’s Rebellion the “society with slaves.”8 A society with slaves

was very similar to what Breen and Innes found in “Myne Own Ground.” Africans could work

towards their freedom and had some liberties even if they were enslaved. Berlin would go on to

call the society after Bacon’s Rebellion a “slave society.”9 A slave society was more brutal and

repressive. Slaves had neither liberties nor freedoms. The shift between the two societies was

once again Bacon’s Rebellion.10

The male writers neglected to add gender issues to the equation. In the 1990’s Kathleen

M. Brown wrote, Good Wives, Nasty Wenches & Anxious Patriarchs, which added a much

needed feminist touch to colonial Virginia’s history. Brown did an excellent job in explaining the

rise of patriarchy. Patriarchy is the total control over a family by a single male figurehead. In

T.H. Breen and Stephen Innes, “Myne Owne Ground:” Race and Freedom on Virginia’s Eastern

Shore, 1640-1676 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980) 1-6,107-108.

7

8

Ire Berlin, Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America (Cambridge,

Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press,1998) 8.

9

Ibid, 8-9.

10

Ibid, 1-14.

5

1705 the slave codes were enacted giving white males extraordinary power over their

households. This power eventually caused them to be more brutal to slaves and in some cases

brutal to their family members as well. Brown’s explanation of the rise of patriarchy coincides

with Berlin’s time line of slave society, and Morgan’s timeline of the rise of slavery. Essentially,

as slavery got more brutal so did patriarch’s control of all aspects of life.11

Brown, Innes, Breen, and Berlin did an excellent job mapping out the social structure of

slavery between 1600 to about 1750 but they did not give a clear picture as to how Bacon’s

Rebellion unfolded. Morgan does do an excellent job in mapping out how Bacon’s Rebellion

unfolded, but recent scholarship regarding the Indians was unavailable to him. James D. Rice is

the most recent scholar to be published on the actual events of Bacon’s Rebellion. In his book

Tales from a Revolution: Bacon’s Rebellion and the Transformation of Early America, he goes

into great detail to explain how Bacon’s Rebellion unfolded, especially on the side of the

Indians. It is because of Rice that we see the Indians’ perspective on Bacon’s Rebellion.12

Many historians have covered slavery in early Virginia and Bacon’s Rebellion, but they

do not share the common link that that Morgan, Brown, Innes, Breen and Berlin have. They all

argue that Bacon’s Rebellion was the pivotal moment that changed slavery, race and gender

relations in the colonies. Each represents a different style and time period. Morgan focuses on a

wide scope of Virginia’s history through the lens of the civil rights movement. Breen and Innes

focus on slavery before Bacon’s Rebellion with a special emphasis on actually free Africans,

living amongst the whites. Berlin focuses on slavery before and after Bacon’s Rebellion with a

broader brush stroke on African lives. Brown puts a feminist twist to Virginia’s history that the

11

Kathleen M. Brown, Good Wives, Nasty Wenches & Anxious Patriarchs: Race and Power in

Colonial Virginia (Chapel Hill, North Carolina, The University of North Carolina Press, 1996) 319-324.

12

Rice, Tales from a Revolution.

6

men have overlooked. All of them argue from different perspectives, time periods, and cultures

but the one constant in their writings is that Bacon’s Rebellion shaped the Virginian society,

slavery and race relations.

Thesis:

In this essay I will argue that Bacon’s Rebellion caused the elites in colonial Virginia to

be frightened of another uprising, in turn they enacted a more patriarchal, brutal, and segregated

slave system to keep their economic and political control. Part I of this essay deals with

seventeenth century Virginia prior to Bacon’s Rebellion. During this time period Virginia

became one of the most prosperous colonies in the New World. Slaves in Virginia were given

autonomy and the ability to purchase one’s own freedom. Part II deals with Bacon’s Rebellion.

The actions of Nathaniel Bacon and Governor William Berkeley left Virginia in a state of chaos

after 1677. Overall, Bacon’s leading of the poor and the enslaved against the Governor sent

shockwaves down the spine of elites. This forced them to take action to regain control. Part III

deals with the elite’s response to Bacon’s Rebellion. They tried to maintain stability in the

colony by enacting laws and social customs to oppress and brutalize the workforce, which

changed from a servant majority to a slave majority. The frantic state of Virginia after Bacon’s

Rebellion pushed the richest plantation owners to a more brutal form of slavery. With their

power and influence they slowly caused all of Virginia’s planters to switch their labor to slavery.

Their actions have had wide ramifications for slavery and race in America.

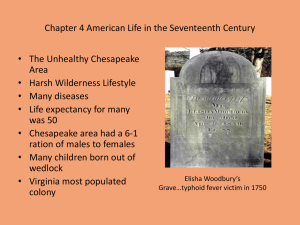

Part I: Lives of Slaves Before Bacon’s Rebellion, 1620-1675

Historically, Virginia was one of the most important colonies in American History. Three

of our first four presidents called Virginia home and all of them owned slaves. It was one of the

7

major hubs for political and economic culture in the thirteen colonies. But Virginia has a darker

side as the center for America’s slave culture. The plantation owners in Virginia escalated the

importation of enslaved Africans into the colonies so they could cultivate more of their cash

crop: tobacco. But the form of chattel slavery that plagued eighteenth and nineteenth century

America was not an inevitable institution. The lives of all Africans changed after the events of

Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676. Before then slaves had limited rights. Some took these limited

freedoms and worked miracles becoming well—respected members of society. Others received

marginal benefits. The rise of a more racial and segregated south was not written in stone, it was

a gradual process. To better understand this process we first need to look at Virginia’s overall

culture before 1676.

In 1492 Christopher Columbus set sail east to find a route to Asia and claim their riches

for Spain. When Sir Walter Raleigh of England founded Roanoke, Virginia, in 1585 his goal was

no different. The English settlers came to Virginia to discover gold and a passage—way to the

Orient. Inspired by how much money Spain was able to obtain from colonization in the New

World, English merchants started their own company in the hopes of finding the same treasure.

The gold brought from the New World to the Old made Spain the most powerful European

power in the seventeenth century. But the settlers in Virginia were disappointed to find no gold,

great treasures or passage way; only “savage people” and a climate that seemed hostile to

newcomers. But the Virginians were determined to find a way to make a profit from their land.

That profit eventually came in the form of a plant: tobacco. To the Virginians it became their

close equivalent to gold. In the southern colonies before King Cotton reigned supreme, the

people were praising King Tobacco.13

Morgan, American Slavery, 25- 44; Morgan, “Slavery and Freedom” The Journal of American

History 59 (1972) 6-15.

13

8

King James I was fighting for a lost cause when he denounced smoking tobacco as “A

custom loathsome to the eye, hateful to the nose, harmful to the brain, [and] dangerous to the

lungs.”14 His emphatic statement about the evils of smoking was widely ignored. King James’

subjects were unapologetic for their love of tobacco. The craze started in 1619 when John Rolfe,

a prominent Virginian, learned from the Indians how to cultivate the crop. Because of his work

with the natives Rolfe was able to produce England’s first successful tobacco crop that same

year. Virginia’s climate is perfect for growing tobacco. The plant thrives in a long, hot and

humid growing season, and when grown under those conditions the crop will have a better yield,

better taste and have a higher content of nicotine. This causes a more sensational high for the

smoker and a more addicted clientele for the producer. Virginian’s tobacco was a much better

quality and was cheaper than New Spain’s. These factors caused tobacco to fly off the boats and

into the hands of eager consumers.15

While Europe was frantic for tobacco, Virginians were equally frantic trying to produce

it. According to John Pory, a prominent Virginian plantation owner, in 1630 one man working a

modest farm could make £200 sterling. But with six servants John Pory stated that he made

£1,000 sterling.16 If John Pory is right that would have made planters with servants extremely

prosperous. To quantify this, according to Measuringworth.com £1,000 sterling in 1630 would

14

Alan Taylor, American Colonies: The Settling of North America (New York: Penguin Books Inc.

2001) 134.

15

Morgan, American Slavery, 108-111; Taylor, American Colonies, 133-138.

Edmund S. Morgan, “The First American Boom: Virginia 1618 to 1630,” The William and Mary

Quarterly 28 (1971) 176-9.

16

9

be the equivalent of making £3,000,000 today, which is around $5,000,000.17 It should be noted

that there is an incentive to lie about the amount of money one would make or tobacco one

would produce. Nobody wants to be the failure in a group and everyone wanted to outshine their

fellow plantation owners. But even so, the amount of money that the plantation owners made far

exceeded that of the average Englishmen back home and even some noble men.18

Tobacco became so important to the plantation owners that they sometimes put self—

preservation second.19 During Indian attacks settlers occasionally refused to join the militia. It

seemed crazy to them to leave the tobacco crop because it was so valuable. Even in the face of

famine, King Tobacco reigned. Many farmers refused to plant corn, thus choosing to go hungry

throughout the winter rather than give up one acre of tobacco. This became such a problem in

Virginia that the courts needed to enforce regulations on how much corn needed to be grown per

plantation. But people seldom followed the court order and chose to buy imported food from

England or trade/pillage food from the Natives. The money that flowed into Virginia was

abundant and planters were trying to make as much as possible.20

Tobacco became everything to the Virginians. Laws and debts were written in payments

of tobacco in pounds. Land was quickly being bought up, or stolen depending on your

perspective, to cultivate the crop. Many of the men who came to Virginia during the tobacco

boom were second sons of noble families trying to make it in this lucrative industry. And with

“Purchasing Power of British Pounds from 1270 to Present,” MeasuringWorth.com, Last Accessed:

May 6, 2014, http://www.measuringworth.com/ppoweruk/. This website uses a calculator to determine

how much money, in this case pounds sterling, has inflated since 1270. The date 1630 and the amount of

£1,000 sterling were entered into the calculator to obtain the value.

17

Morgan, “The First American Boom,” 76-9.

18

19

Morgan, American Slavery, 112.

20

Ibid, 111-36.

10

simple logic they found ways to make even more money. More hands and legs meant more

tobacco cultivated. So, as the tobacco supply increased so did the demand for labor. Incoming

servants met the demand.

The demand for labor helped England socially as much as it did economically. In the

sixteenth and seventeenth century England’s population grew more rapidly than its economy,

leaving thousands of homeless citizens on England’s streets. These vagabonds were usually

begging and scavenging for food and money. In response the English government passed the

enclosure policy. This exacerbated the problem because it seized lands and evicted many people

from villages that they saw as their homes. Thus, the government’s policy of enclosure caused

more people to be on the street. England sought another solution to the growing number of

impoverished. Their answer was to ship these poor people as servants to the new world. Many of

them came to Virginia with a promise of a fresh start. It was a win for the plantation owners and

English government. Plantation owners received labor to create more tobacco and the English

government found a solution to their growing numbers of impoverished.21

Virginia’s industry was built on two types of servants: wage laborers and indentured

servants. Wage laborers were workers who worked on plantations for agreed upon monetary

payment, usually for one growing season. They made up only a small percentage of the workers

in the Chesapeake. Indentured servants were the main workforce. During the seventeenth century

indentured servants composed three-quarters of the emigrants to Virginia.22 They worked under

their master for a certain amount of years; usually, the agreement was seven. When that time of

21

David Brion Davis, Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World (New York:

Oxford University Press, 2006) 132.

22

Taylor, American Colonies, 142.

11

their service was up they would obtain their headright, which was a legal agreement to a plot of

land after one’s time of service was up. This enticed many poor people in the greater United

Kingdom who probably would not have fared well in England. Many of them were orphans,

criminals or the vagabonds (discussed previously), who were thought to be given a tremendous

opportunity. blacks could be indentured servants as well. Many blacks from New Spain came to

Virginia. They were sold to plantation owners as indentured servants. Some former slaves from

the English colony of Barbados came to Virginia and were also sold as servants. Even though

this system had a promise for escape it was in actuality all a farce. Servants seldom outlived their

contract. This is why plantation owners were so enticed by indentured servants because if they

did not outlive their contract they would not obtain their headright. Masters over—worked their

indentured servants right before their contract was up, guaranteeing that they would die. If the

cruelty of their masters didn’t get them, diseases or starvation would. Going to Virginia as a

servant meant you had a very high probability of dying.23

From 1618 to 1630 tobacco was at its peak prices. Previously discussed was how

insanely rich plantation owners were becoming. But after 1630 the tobacco prices started to

plummet. England started to have a great a surplus of tobacco. Unused tobacco filled up

warehouses all over England’s port cities. There was so much tobacco that if plantation owners

had a bad yield one year they could live off the tobacco stored in barrels from last year. But the

vast sums of wealth obtained during the tobacco boom enticed many new investors to test the

waters of the tobacco market in Virginian. Both the newcomers and old—timers hoped that the

price of tobacco would increase back to boom levels. But their hopes were in vain. Tobacco

23

Winthrop D. Jordan, White Over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550-1812 (Chapel

Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 1968) 47; Taylor, American Colonies, 142-4;

Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 132-33.

12

levels would stay steady throughout the century at record low prices. These plantation owners

remained steadfast on earning boom years prices. In their minds the only way to obtain more

money was to grow more of it; which probably exacerbated the problem. Nonetheless lands were

quickly bought up to produce more tobacco. With these new lands more laborers were brought

into work. All so the owners could chase the high of the early 1600s.

In the Spanish colony of Hispaniola slavery was created during the boom years of their

cash crop: sugar. Even in other English colonies such as Barbados, plantation owners were

turning to slaves to do their dirty work. But in Virginia indentured servitude was the main labor

force. Ships full of slaves did not come into Virginia’s ports until later in the century.24 There

were only a handful of Africans in Virginia from 1610-1640. And it is disputed whether they

were slaves or not. But it is greatly accepted by most historians that the first massive wave of

slaves came into Virginia around the 1640s. The driving force for the changes in labor was the

low birthrates in England. The English Civil War caused massive casualties which caused

birthrates to plummet in the 1640s. Workers were needed back in England to help rebuild the

country. The shortfall of labor caused an increase in wages and jobs. All of those poor people in

England finally found their place back at home. They were no longer willing to go on the ships

to the new world. Many other migrants and servants chose to go to other colonies such as: New

York, South Carolina, Maryland and New England. To meet the shortfall of labor plantation

owners started to import slaves.25

It is a fruitless endeavor to try to make a claim that one form of slavery is better than

another because slavery is inherently immoral. But slavery in the seventeenth century was

24

Morgan, American Slavery, 133.

25

Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 132-133.

13

drastically different from that of eighteenth and nineteenth century. Slavery during the eighteenth

and nineteenth centuries was extraordinarily brutal and there was little hope of freedom. Slavery

before the 1700s was much different. Ira Berlin, a historian from the University of Maryland,

called the early colonial society, “societies with slaves.”26 He would later call the society of the

eighteenth and nineteenth century “slave societies.”27 What Berlin meant by societies with slaves

was that in early colonial America, especially Virginia, slavery was not central to the economy.

It was not the backbone of industry like slavery was in the antebellum south. It was just an

institution. To put it simply, they were a society that happened to have slaves. This is not to say

that slaves in a society with slaves had it easy. Slave holders could be extraordinarily cruel and

they ruled unilaterally, but unlike the antebellum south slaves had a greater chance at freedom.

Slaves could work towards their own liberty. The way Virginians interacted with Africans in the

middle of the seventeenth century, both free and enslaved, is also drastically different then the

way they acted towards blacks later on.28 Slavery was defined by race, but an African’s life was

not. That is to say, slavery was racial because only Africans were slaves but it did not mean that

racism and discrimination existed for those who were free and for some of those who were

slaves.

Anthony Johnson is one of those Africans who benefited from the society with slaves and

had virtually no problems because of it. He is one of those rare cases of slaves, or servants,

actually obtaining their freedom. According to court records Johnson first arrived in Virginia in

1621. Bought by the Bennett family his labor was used to cultivate tobacco. Anthony Johnson’s

26

Berlin, Many Thousands Gone, 8.

27

Ibid, 8.

28

Ibid, 1-10.

14

status as a slave or servant is widely disputed amongst historians. T.H. Breen and Stephen Innes

in “Myne Owne Ground” reluctantly call him a slave.29 Others like Kathleen Brown in Good

Wives and Ira Berlin in Many Thousands Gone take the stance that he was absolutely a slave.30

Brown and Berlin indicated that all of the Africans during the period were mostly slaves. But

other historians disagree. Alden T. Vaughan wrote in American Genesis that it is hard to

determine what the status was of the very few Africans in Virginia before 1640. He argues that

black servants were somewhat lower than white servants but were not quite slaves. So Africans

that came to Virginia before 1640 were servants.31 Because this essay draws heavily on Breen,

Innes, Brown and Berlin’s work I will continue to refer to Anthony Johnson and the other

Africans in Virginia prior to 1640 as slaves unless stated otherwise, noting that there is scholarly

conflict on the matter.

On March 22, 1622 nearby Indians attacked and killed over 350 colonists. Johnson

survived the attack and because of it gained favor by his owner. Johnson received special status

amongst the other slaves and servants. He was officially recognized for his, “hard labor and

known service.”32 Because of this status Johnson was given a plot of land to farm independently.

This eventually would be used to fund the purchase of his freedom. He also was allowed to

marry. He married another slave on the plantation by the name of Mary. They bore children and

Breen and Innes, “Myne Owne Ground,” 7-10.

29

30

Brown, Good Wives, 109-111; Berlin, Many Thousands Gone, 29-30.

31

Alden T. Vaughan, American Genesis: Captain John Smith and the Founding of Virginia (Boston:

Little, Brown and Company, 1975) 147-149.

32

Berlin, Many Thousands Gone, 30.

15

baptized them as Christian. Johnson is one of those rare cases of a slave actually making it in the

new world. Soon he would have his freedom and be able to start a great life with his wife.33

Johnson’s wife Mary should not be just an afterthought. She too had an interesting life. It

is most likely that Mary was a slave from Guinea or the Kongo-Angola region. She was traded to

Portuguese slavers by her kingdom sometime in the 1620s. When she was brought to Virginia

according to historian Kathleen M. Brown she was only one of 10 African women in the whole

colony. She, like her husband, was also known as a hard worker and probably obtained her

freedom by her own merits.34

In 1645 Anthony Johnson gained his freedom. One day in that year he was with Mr.

Edwyn Conaway, the court clerk, and Mr. Taylor his new next-door neighbor. While looking at

his corn field Johnson said to Mr. Conaway that, “Mr. Taylor and I have divided our Corne And

I am very glad of it {for} now I know myne Owne, hee finds fault with mee that I doe not worke,

but now I know myne owne ground and I will worke when I Please and Play When I Please.”35

Johnson obtained 250 acres on that day. On his farm he grew tobacco and raised livestock.

Johnson soon became an elite plantation owner. He even owned slaves and continually bought

more land just like any other Virginia farmer. Johnson’s sons were also successful plantation

owners. His son Richard owned 100 acres and his other son John owned 550 acres. Soon the

Johnson family would be a powerful family in Virginia. But even with all of his success and

wealth an unfortunate fire happened on Anthony Johnson’s farm that almost derailed all of his

Breen and Innes, “Myne Owne Ground:” 7-13; Berlin, Many Thousands Gone, 29-31.

33

34

Brown, Good Wives, 107-110.

Breen and Innes, “Myne Owne Ground,” 6; Susie M. Ames, County Court Records of AccomackNorthampton Virginia 1640-1645 (Richmond, Virginia: The University Press of Virginia Charlottesville,

1973) 457.

35

16

success. The fire destroyed most of the crops. Johnson soon needed to ask his white neighbors

for assistance. But would they lend a former slave a hand?36

The investigation of the fire by the Northampton County Court ruled that Johnson would

not be able to make a sustainable living off the scorched land without the help of the community.

The court decided that in order to offset the loss that the Johnson family attained they would

reduce their taxes. This was a common practice in the seventeenth century when people were in

need. But, the court took it a step further by eliminating the tax duty for Johnson’s daughters.

Certain taxes in the seventeenth century were charged to an individual working person. In

Virginia taxes were associated with a man’s labor per plantation. African women were

considered to be doing traditional manly duties. Essentially, the only form of labor not taxed was

white women’s labor. This is because it was viewed that white women would do more domestic

work. Abolishing tax duties on Johnson’s daughters meant that in the eyes of the court Johnson’s

black daughters were no different from any other plantation owner’s white daughters. This

court’s decision points to the fact although Johnson was a slave because of being African, his life

was not hindered because of it. This situation is allowed to be possible in a society with slaves.

The white court saw the Johnson family had a problem, so they helped him the best way they

could. By doing so, they raised the Johnson family to the same status that any white plantation

owning family would have had.37

There is one last notable case where Anthony Johnson shows us how he was viewed as an

equal to his white neighbors and not judged based on race. According to the court records

Anthony Johnson was accused by one of his slaves, John Casor, of being detained illegally by

Breen and Innes, “Myne Owne Ground,” 6-10; Berlin, Many Thousands Gone, 31-32.

36

Breen and Innes, “Myne Owne Ground,” 7-12; Browne, Good Wives, 116-117.

37

17

Johnson. John Casor stated that he was an indentured servant who was free until Johnson forced

him into slavery. A man by the name of Robert Parker investigated the incident. Trying to steal

someone’s labor was common practice in Virginia. If proven guilty one needed to pay a hefty

fine. Robert Parker was not afraid of such fines because he took John Casor in the middle of the

night claiming that he was free. Casor then worked on Parkers plantation. Historians are unsure

why Casor hated Johnson so much. He was still a slave under Parker. But nonetheless, Johnson

did not take this incident lightly. He sued Parker for his stealing a slave. One would think that a

court of white slave owners would side with the other white slave owner in a lawsuit against a

former slave, but they did not. Johnson won his lawsuit and his slave was returned to him. Also,

Parker needed to pay hefty fines.38

The white court saw Johnson as a man with a problem. Not as an African man. To think

that only a few decades later Mr. Johnson would not be allowed to even testify in court is a

drastic difference in the mindset of southerners. It would be unfathomable to think that a case

like this would happen in the antebellum south because courts never sided with blacks. There is

no better example of the how vastly different a society with slaves and a slave society are, than

in Anthony Johnson’s case. In a society with slaves he was able to obtain his freedom, marry,

own a farm, and in his times of trouble receive a helping hand from his fellow farmers. He, a

former slave, also was able to own a slave and no one seemed to be bothered by it. Race was not

a hindrance to his life accomplishments. Freedom wasn’t a carrot on a stick. It was tangible.

Racial slavery existed in the societies with slaves, but discrimination was not acted upon after

freedom.

Breen and Innes, “Myne Owne Ground.” 10-18; Berlin, Many Thousands Gone, 31.

38

18

Certainly though, Johnson was not the only person with African origin to benefit. The

same system that allowed Johnson to become free benefited many enslaved Africans. Francis

Payne was a slave who obtained his freedom. His payment was a little bit more unusual than

most. In exchange for his freedom Payne needed to provide his master with enough money to

purchase three white servants. Payne calculated the cost and planned a strategy to make the

money. He eventually was able to obtain the money needed and thus, received his freedom.

William Harman took the traditional route by paying his master 5000 pounds of tobacco for his

freedom. Unfortunately, not everyone succeed. Emanuel Driggus tried his best to purchase the

freedom of his whole biological family and several children that he took in as their own. But the

cost was too great for Driggus. He watched while the family members he was unable to purchase

were sold one by one into permanent bondage.39 Allowing the slave to work toward their own

freedom did nothing to impede plantation owners’ gains. Under this system slaves needed to use

their land to feed and clothe themselves. With the slaves essentially taking care of themselves

owners could put most of their focus on tobacco. It also gave the slave something to be proud of

and a glimmer of hope. Whatever the slave grew on that plot of land was his to sell and in many

cases that meant buying either their own freedom or their family’s freedom.40 The old adage

“you catch more bees with honey, than you do with vinegar” seems to fit well here. Plantation

owners were not giving out this land for charity. Rather the calculus behind this system was

control. Slaves would be less likely to jeopardize the “privilege” of being able to obtain freedom

by doing something rebellious. No matter the motive behind the system, some Africans benefited

greatly.

Breen and Innes, “Myne Owne Ground,” 71-77.

39

40

Berlin, Many Thousands Gone, 33.

19

What slaves did with such little land was simply remarkable. Slaves grew crops and

raised livestock, selling them to either their masters or other plantation owners. Others became

manufacturers creating small items that were also bought and sold to other plantation owners.

For example, shoe making and tool crafting was a common practice amongst the slaves. For the

plantation owners buying the goods it was a great thing. They bought the tools they so

desperately needed without paying for the high price of English tools. Hunting and fishing was

another way the slaves made money. If a slave killed a deer it was likely that part of the meat

would be on the owner’s table, but at a price. All of this was allowed to happen because owners

gave the slaves just a small patch of land for themselves and some free time. Ira Berlin calls the

economic output of these slaves, “The slave economy.”41 Slaves helped owners and owners

helped the slaves. And soon free slave communities were forming all around the Chesapeake; all

because slaves were able to work toward their freedom.42

European slavery was intrinsically racial. Africans were enslaved because they were

black. One can argue the origins of why Africans were enslaved; but it is an endeavor I intend to

forgo. But we see in the slave economy of Virginia and the life of Anthony Johnson that

xenophobia and discrimination did not seem to be the status quo. Plantation owners seemed to

benefit greatly from the limited freedoms slaves had. It also offered a glimmer of hope that was

unprecedented in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In this brief window in colonial

Virginia free blacks were considered no different from the other farmers in the community. How

did the mindset of southern society change so quickly? The shift from the system of servitude

and slavery previously discussed to the more brutal system of slavery seems to hinge around

41

Ibid, 33.

42

Ibid, 33-88.

20

Bacon’s Rebellion. The events of Bacon’s Rebellion marked a paradigm shift in the way large

plantation owners did their business and why they were so eager to escalate slavery. Eventually,

their future success would shift the way smaller plantation owners would do their business thus,

changing the whole dynamic of black and white relations in the south. It is after Bacon’s

Rebellion that we see how laws fundamentally change so that whites and blacks would be

permanently separated. To understand why this shift occurred we must understand what Bacon’s

Rebellion was and why it happened at all.

Part II: Bacon’s Rebellion, 1676

Nathanial Bacon had an incredible knack for creating a tumultuous environment for the

people in his life. He was the only son of wealthy merchants Thomas and Elizabeth Bacon. Due

to birthing complications Elizabeth died, leaving Thomas to raise Nathanial and his six sisters

alone. Being the only son Nathanial received special treatment. He was given a fairly large estate

and an excellent education at Cambridge University, the two things needed to be successful in

seventeenth century England. Sometime after his graduation Nathanial met and married

Elizabeth Duke, the daughter of Sir Edward Duke, a wealthy land owning aristocrat.

Unfortunately, Duke already promised his daughter’s hand. But Nathanial and Elizabeth refused

to annul. Sir Edward Duke then disowned his daughter. Soon after their marriage Nathanial was

embedded in another scandal. He was sued regarding a fraudulent land deal. Thomas decided

that in order to avoid lawsuits and court proceedings it would be best if his troublesome son just

went away. Since Nathanial and Elizabeth were good friends and close relatives with the Royal

Governor of Virginia, William Berkeley and his wife Frances Culpeper Stephens (Lady

Berkeley), Thomas gave Nathanial and Elizabeth £1,800 sterling to start a new life in Virginia. It

21

was meant to be a fresh start, but Bacon’s special talent for causing trouble followed him to

Jamestown.43

When Nathanial and Elizabeth arrived in Virginia in 1674 the Berkeleys happily received

them. The Governor sat with Bacon and mapped out two nice plantations near the James River.

The lands were fertile, well irrigated and perfect for growing tobacco. But Bacon found fault

with them. They were on the frontier far away from Jamestown, the capital and trading hub of

Virginia. Unfortunately Bacon came to Virginia at the wrong time. Wealthy planters during the

tobacco boom had bought all of the available lands close to the shore. In addition, treaties with

the Indians marked a well-defined line between Indian territories and colonial settlements. No

new lands or buffers were going to be available anytime soon. If land away from the Indians

happened to become available Berkeley always gave preference to his closest friends. Although

Bacon was a close friend of the governor he was new to Virginia and not officially in Berkeley’s

close knit social circle. These three factors forced newcomers like Bacon to take lands near the

frontier. Begrudgingly Bacon, and the subsequent investors, took the lands and started to farm.44

The frontier was a dangerous place to live. The Indians were consistently being pushed

into the interior by the colonists and they had enough. The tribes most affected were the

Susquehannahs, Doegs and Piscattaways. The Susquehannahs were pushed back so far that they

started to encroach on other tribes’ lands. The Susquehannahs responded by attacking frontier

farmers. Unfortunately for the Indians the English were too numerous and better armed. The

Susquehannahs could not mount a full onslaught against the colonist. But The Indians had the

43

Alfred A. Cave, Lethal Encounters: Englishmen and Indians in Colonial Virginia (Santa Barbara,

California: Praeger, 2001) 154; “Nathaniel Bacon (1647–1676)” Encyclopedia Virginia, Accessed April

27, 2014, http://encyclopediavirginia.org/Berkeley_Frances_Culpeper_Stephens_b_ap_1634-ca_1695.

44

Michael Leroy Oberg, Samuel Wiseman’s Book of Record: The Official Account of Bacon’s

Rebellion in Virginia, 1676-1677 (New York: Lexington Books, 2005) 17; Brown, Good Wives, 138.

22

distinct advantage of being expert woodsmen and marksmen. Indians used quick and sly attacks.

After their skirmish was done they would run into the woods and hide. Although theoretically

the English could out muscle the Indians they could not destroy them. They were simply too

evasive. Governor Berkeley’s strategy toward the Indians was to use a defensive policy. He

wanted more forts and men on patrol to keep the Indians from attacking and the colonist from

attacking the Indians. This action alienated many colonists who lived on the frontier. They

believed that the Indians needed to be dealt with swiftly. Sometime around 1675 or 1676 a

petition was signed by the frontier colonist requesting that Berkeley take action. It stated,

Petition of your poor distressed subjects in the upper parts of James River Virginia to Governor Sir

William Berkeley. That the Indians have already most barbarously and inhumanly taken and

murdered several of their brethren, and put them to most cruel torture by burning them alive; that

they are in daily danger of losing their lives, and are afraid of going about their domestic affairs.

Request they may be granted a commission to make a choice of commission officers, to lead this

party now ready to take arms in defense of their lives and estates…45

The colonists were in favor of an offensive attack. Berkeley’s defensive strategy made them feel

alienated by the governor.46

Berkeley’s neglect of an offence comes as no surprise. King Philip’s War was fresh in the

governor’s mind. In 1675 colonists from Plymouth, Massachusetts captured, tried, and executed

three Wampanoag Indians for the murder of a Praying Town (Christian Indian community)

Indian who served as a colonial informant. The Wampanoags were led by Metacomet, whom the

English referred to him as King Philip. Metacomet did not stand idly by while his people died.

He led his warriors in a massive wave of violence against the colonist. As the violence spread

more Indian tribes came to the side of the Wampanoags. They too were fed—up with the English

Robert Middlekauff, Bacon’s Rebellion (The Berkeley Series in American History) (Skokie, Illinois:

Rand McNally, 1964) 5.

45

46

Middlekauff, Bacon’s Rebellion, 3-5; Morgan, American Slavery, 252-3.

23

encroachment on their lands and torment of their people. The colonists’ own ignorance soon

served to be their downfall. Many of the colonist retaliatory attacks were against neutral Indian

tribes. Those tribes then joined the Wampanoags in their attempt to kill the ignorant colonist.

The Indians in New England had the numbers but they also had the technology. English

merchants were illegally trading guns to the Indians for goods. The colonists main advantage

was now gone because of their own lack of foresight. Years of bad Indian policy and ignorance

towards native culture caused this destructive war.47

During King Philip’s War the Indians enacted a total war policy. They killed every

colonist; even women and children. The Indians in New England were just as evasive as the

tribes in Virginia. When colonists attacked, the Indians would run into the woods and hide

amongst the trees. There, the Indians’ true skills could shine. As the English came into the forest

they were slaughtered by the better woodsmen. King Philip’s War was a massacre for the

colonists. By early 1676 the New Englanders saw that they could not defeat their enemy without

the help of the last remaining neutral native tribes. Indian tribes who were either weak or

unfriendly with the Wompanoags joined the colonists. Those alliances were instrumental in

helping the English locate the illusive Indians. Thus, after 1676 King Philip’s War became just

as much a civil war between the Indians as it was a war against the colonists. After two years of

combat the Wompanoags and their allies simply ran out of bullets, powder, and food. With a bit

of luck and new allies the New Englanders finally were able to defeat the Wampanoags. King

Philip’s War claimed the lives of 1,000 colonists and 3,000 Indians.48

47

Taylor, American Colonist, 199-202.

48

Ibid, 199-202.

24

Berkeley was well aware of King Philip’s War. He believed that an all—out offensive

against the Indians would cause an Indian conglomeration against the Virginians. Creating a

buffer—zone between the Indians and the colonists would be the best way around war.

Berkeley’s Indian policy did not exclusively focus on protecting the colonist. An enormous

reason for Berkeley favoring a defensive policy was his monopolization on the Indian fur trade.

Berkeley was only allowing his inner circle the privilege of trading for Indian furs. Keeping

Indians happy benefited Berkeley and his friends’ personal monetary success. The last thing he

wanted was an Indian embargo on trade. Nonetheless, the defensive policy was good strategy.

King Philip’s War had escalated because the New Englanders were slaughtering any Indian they

saw, not respecting tribal differences. The Virginians would have probably gone the same route

as the New Englanders, causing a massive war in Virginia.49

One night in April, 1676, Bacon and some of his closest friends were in Henrico Country

enjoying a few drinks. They were discussing a rumor that the Indians had stopped working their

corn fields. It was a sign that they were preparing for another attack. Bacon and his friends all

lost workers due to Indian attacks. The frontier planters were angry at Berkeley and the House of

Burgesses’ policies towards the Indians. They were acutely aware of how much Berkeley

profited from good relations with the Indians and were perturbed at his profit from their plight.

Their solution to the Indian problem was eradication or enslavement. While this conversation

was happening other planters gathered a few miles away. They too were irate about the

governor’s Indian affairs. When word spread of this meeting Bacon and his friends hurried to the

crowd. Soon frontier planters from across Virginia gathered together to find a solution to the

Indian problem. Everyone there knew Nathanial Bacon as a smart man who had a deep—seeded

Morgan, American Slavery, 252-3; Taylor, American Colonies, 147; Oberg, Samuel Wiseman’s, 14.

49

25

hatred for the Indians. The crowd also knew of his high profile relationship with Berkeley. They

chose Bacon as their leader because of his friendship with the governor. They hoped that if

Bacon was the figurehead of their campaign then Berkeley would give his longtime friend a

royal commission giving him the authority to war against the Indians. Bacon accepted the

position of power and according to Edmund S. Morgan, “(gave) out a supply of rum like a good

politician.”50 He seemed to please the crowed his first night on the job.51

Bacon was quick to accept the crowd’s request because he also believed Berkeley would

give him an official commission. He too knew the ramifications of King Philip’s War, but from a

different perspective. In Bacon’s mind if the Indians were kept alive then they would eventually

kill the colonists. The frontier planters did not want to live with the Indian attacks. They wanted

more land to expand into Virginia’s interior. Essentially greed was their motive. More land

meant more profit for the new planters who had missed the massive land grab in the middle of

the century. It is because of these factors that Bacon and the other planters decided the Indians

needed to be eradicated. The planters on the frontier found themselves a champion in Nathanael

Bacon.52

For Berkeley, Bacon’s new army was more alarming than any Indian tribe. Berkeley was

astonished that a newcomer, such as Bacon, believed he could take Indian affairs into his own

hands. Equally as frightening was how many were willing to join him. Berkeley understood that

many of these planters who joined Bacon had resentment towards the government. Bacon’s

army had many poor farmers. Low prices for tobacco meant small time farmers could easily fall

50

Morgan, American Slavery, 256

51

Morgan, American Slavery, 254-6; Brown, Good Wives, 159-61.

52

Morgan, American Slavery, 255-257.

26

into misfortune. Large plantation owners could live with the low prices because they were

growing such vast quantities and Berkeley made sure the large plantation owners were always

well off. He gave them exclusive rights to trade with the Indians and tax breaks. These practices

were widely known and hated by small farmers. Why should the least get nothing while the rich

get richer? If the violence got out of hand Berkeley was afraid that the army of poor farmers

would find their way to Jamestown. But Bacon was aware of this. He understood how dangerous

these poorer white farmers could be if things got out of hand. Bacon saw the war against the

Indians as a way to ease the tensions of the colony. Once they were done killing the Indians the

poor would overlook their woes with Berkeley. Bacon viewed the war against the Indians as a

cathartic experience for the colonist. Berkeley certainly did not trust Bacon’s cathartic thesis. He

was afraid Bacon was spearheading a mutiny. He tried to calm the situation by announcing new

elections for the House of Burgesses. This was done so the people on the frontier could air their

grievances without escalating to violence.53

While Berkeley was trying to defuse the situation Bacon did more to exacerbate it. The

Occdaneechee Indians, near the North Carolina border, had recently fought a battle with the

Susquehannahs. One of the Occdaneechee leaders invited Bacon to come to his main fort and

partake in a celebration; after all, the enemy of your enemy is your friend. While there Bacon

received gifts. They were the severed head of the Susquehannah war party leader, beaver pelts

and a few Susquehannah prisoners. Bacon ordered that the prisoners be executed and the

Occdaneechee followed through. Although the Occdaneechee were friendly towards Bacon, he

wanted the full eradication of the Indians. The Occdaneechee were not aware of this. Bacon

53

Wesley Frank Craven, White Red and Black (New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc., 1977) 2021; Morgan, American Slavery, 250-257; Rice, Tales from a Revolution, 42-44

27

ordered his men to open fire against the unsuspecting Occdaneechee. Men were placed around

the palisaded walls and the front gate. They slaughtered the tribe, killing every Indian they could

find.54

Surprisingly Berkeley was somewhat relieved by Bacon’s actions. It reassured him that

this army may not be out to get him after all. But because Bacon broke the law he still needed to

be punished. Berkeley could not have a rogue army roaming Virginia, even one that is true to

their word. Berkeley demanded Bacon disband the army and in return he and his fellow rebels

would receive a full pardon. But the army refused to give up their cause. Berkeley could not let

this disobedience slide. He and his council took swift action, stating that Bacon and his army

were “rebels.” 55 He also states that Bacon committed “treason.”56 Berkeley summed up his view

on the rebellion in this statement.

Now, my friends, I have lived thirty-four years amongst you, as uncorrupt and diligent as ever

Governor was; Bacon is a man of two years amongst you, his person and qualities unknown to most

of you, and to all men else, by any virtuous action that ever I heard of. And that very action which

he boasts of was sickly and foolishly, and, as I am informed, treacherously carried to the dishonor

of the English nation; yet in it he lost more men than I did in three years’ war; and by the grace of

God will put myself to the same dangers and troubles again when I have brought Bacon to

acknowledge the laws are above him, and I doubt not but by God’s assistance to have better success

than Bacon hath had. The reason of my hopes are, that I will take counsel of wiser men than myself;

but Mr. Bacon hath none about him but the lowest of the people.57

Berkeley later on in his statement called the Virginia colony to arms against Bacon and his

followers. Virginia was on the verge of a civil war.58

54

Rice, Tales from a Revolution, 48-49; Morgan, American Slavery, 259.

“His Declaration against the Proceedings of Nathaniel Bacon by Sir William Berkeley (16051677),” Bartleby.com, Last Accessed: May 6, 2014, http://www.bartleby.com/400/prose/157.html.

55

56

Ibid.

57

Ibid.

58

Morgan, American Slavery, 260.

28

During the rebellion, the elections Berkeley promised were still held in May for the

House of Burgesses. Bacon of course was elected as a Burgess form his county. It’s a

contradiction to be a rebel and a member of the government you are rebelling against, but if there

ever was a person to be in that situation it would be Nathanial Bacon. Communications between

the governor and the rebel were kept intact but they began to break down. When Bacon arrived

in Jamestown for his House of Burgesses duties Berkeley was waiting for him. Even though

Bacon had 50 armed guards, the governor was somehow able to capture him. The details of that

situation are murky. Regardless, while Bacon was imprisoned the governor made him write a

confession of his sins. He then brought Bacon on his knees to the House of Burgesses where

Bacon read his confession to the other members. The governor felt satisfied with Bacon’s

humiliation. He shockingly paraded Bacon and the other rebels. The biggest grievance against

Bacon was not the killing of the Indians but rather that he disobeyed the governor. Berkeley

promised Bacon the royal commission he wanted but only to fight Indians who were against the

Virginians. Bacon left Jamestown humiliated but for the time being there was peace.59

During that session of the House of Burgesses Berkeley tried his best to address all of the

grievances of the frontiersman. He abolished the property qualifications for voting for free men.

The Councilors of Virginia, Berkeley’s inner circle, were no longer exempt from taxes. There

were more regulations placed on government agencies, such as the Sheriff’s department, to make

sure they were not over charging or hassling people. All of these measures were made to lessen

the grip elites had on the general public. Berkeley also made some headway on Indian policy. He

59

Ibid, 260-263.

29

requested an army of 1,000 men be raised to destroy the Susquehannahs. They planned on

turning the Susquehannan lands into corn fields for Virginian.60

Berkeley was trying to find a middle ground between extermination and pacifism. And on

paper this strategy probably would have had good dividends for the Virginians. Unfortunately,

Bacon did not trust Berkeley. He believed the governor would come and seek revenge against

him after his army dispersed. Bacon wanted to make his army stronger, keeping himself

politically relevant. He wanted to strike at Berkeley first before Berkeley could strike him.

Bacon went around Virginia and brought more and more volunteers to his cause. He amassed an

army of 500 men and on June 22, 1676, he arrived in Jamestown with his army. Bacon stormed

the capital building and held Berkeley at gunpoint demanding he receive the royal commission.

Berkeley agreed to Bacon’s terms stating he could raise an army of any size, enslave any Indian,

collect any plunder, and his army was officially part of the English government. With the royal

commission in hand Bacon left Jamestown. Berkeley quickly stated that the royal commission at

gunpoint was invalid. He then got on a boat and went into hiding on the Eastern Shore.

Bacon believed the commission was valid, regardless of Berkeley’s recantation. Before

his army he announced his Declaration of the People. In it Bacon stated all of his grievances

against Berkeley. The first one on the list was,

For having, upon specious pretenses of public works, raised great unjust taxes upon the

commonalty for the advancement of private favorites and other sinister ends, but no

visible effects in any measure adequate; for not having, during this long time of his

government, in any measure advanced this hopeful colony either by fortifications, towns

or trade.”61

60

Ibid, 263-264.

“Bacon’s Rebellion: The Declaration (1676) by Nathaniel Bacon,” History Matters George Mason

University, Last Accessed: April 29, 2014, http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5800.

61

30

The fourth grievances is also telling,

For having protected, favored, and emboldened the Indians against his Majesty’ loyal

subjects, never contriving, requiring, or appointing any due or proper means of satisfaction

for their many invasions, robberies, and murders committed upon us.62

These two grievances have deep—seated ties with Bacon’s first experiences in Virginia. If you

were not part of Berkeley’s inner circle then you were not rewarded with the true riches of the

colony. Most of the grievances came from poor whites, who were being mistreated by the elites

of the colony. What once was a war against the Indians was now quickly becoming a class war.63

Up until this point Bacon’s Rebellion was solely an all—white affair. The one thing all

major plantation owners feared was an insurrection of slaves and servants against the

government. Berkeley and his advisers believed Bacon would not seek to free the slaves or

servants. Secretary Thomas Ludwell stated, “I verily believe it will in short time ruin him, since

by it he will make all masters his enemies.”64 Mr. Ludwell was wrong; Bacon was not

considering freeing the slaves for their services. Ironically, Berkeley was the one who proposed

the idea. He needed to stop Bacon at all cost. Even though his closest advisers believed it was a

bad idea, the army was desperate for men so Berkeley offered freedom for servants and slaves if

they joined Virginia’s army. Bacon heard of this proclamation and without a flinch offered the

same deal. Servants and slaves joined Bacon’s army in large numbers. They saw Bacon more as

a freedom fighter and someone who could get them out of oppression. Why would they want to

fight on the side of their masters, who were enslaving them? Bacon led his army of poor whites,

62

Ibid.

63

Robin Blackburn, The Making of New World Slavery: From the baroque to the Modern, 1492-1800

(New York: Verso,2010)n 256-257; Morgan, American Slavery, 266-269.

64

Ibid, 268.

31

slaves, and servants in a destruction of Indian lands and rich plantation owner estates. On

September 19, 1676, Bacon’s army returned to Jamestown and burned the capital building to the

ground. Bacon also sent part of the army to hunt for Berkeley on the Eastern Shore. No longer

was this rebellion solely about Indians.65

Just when it seemed that Bacon would win, he died suddenly of dysentery. Around the

same time British troops arrived from England. Without their leader the rebellious army split up.

Some of them apologized to the governor and were given pardons. Others were hung. Still, some

fought. A combination of slaves and servants held out till the very end, until a gunboat on the

James River killed them or re—enslaved them.66 But the rebellion truly ended when Bacon was

gone. With no figurehead the poor whites, servants, and slaves were lost.

Bacon’s Rebellion started as an all—out war against the Indians. It then transformed into

a class war between the rich and the poor. Did Bacon really have the best intentions toward the

poor, indentured servants and slaves when he led them against the governor? It is hard to

determine because Bacon died so suddenly. He had no journal that we know of. There is no way

we can fully understand his thought process. The only primary accounts describe his actions and

they are all written by people with biases. In his last month of life it is hard to decipher if he

really was fighting this war for the poor. Who really knows what goes on in a man’s mind?

Examining Bacon’s life makes it seem impossible that he was a freedom fighter. He was land

hungry, greedy, and was willing to kill a whole population to obtain these desires. He was also

down—right arrogant and self—entitled. If Bacon had a seat with the elites then it is more than

65

J. Douglas Deal, Race and Class in Colonial Virginia: Indians, Englishmen, and Africans on the

Eastern Shore During the Seventeenth Century (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1993) 112-113;

Lorena S. Walsh, From Calabar to Carter’s Grove: The History of a Virginia Slave Community

(Charlottesville, Virginia: University Press of Virginia, 1997) 33-34; Morgan, American Slavery, 266269.

66

Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom, 327.

32

likely he would have had no reason to rebel. The real escalation of the violence started after

Bacon was pardoned. Bacon escalated the violence because he wanted to protect himself from

future attacks from the governor. Bacon seemed to be paranoid about Berkeley. But he did spend

months with these poor whites, servants, and slaves. It is completely plausible that he felt a sense

of duty to help them. Regardless of Bacon’s motives or intentions his rebellion scared the elites.

There was a good chance they might have been killed by the rebels if Bacon did not die so

suddenly. They strategized on how to make sure an insurrection of poor whites, servants, and

slaves would never happen again. How would they reestablish control over their colony? The

solution they came up with was brutal.

Part III: The Formation of a Slave Society, 1677 –.

Berkeley successfully defeated Bacon in the fall of 1676, but his efforts did not impress

the King. Berkeley knew that he would be removed from office because of the Rebellion. So in

1677 Berkeley resigned as Governor hedging off any official order. He returned to London

where he eventually died that same year. Berkeley left Virginia in a state of chaos. Even though

he was officially out of power, his inner circle was still in charge. They controlled Virginia’s

political, economic, and social structures. The Historian Edmund S. Morgan calls these

influential planters, “labor barons.”67 They were the ones with the most to lose from Bacon’s

Rebellion. The poor whites, servants, and slaves were rebellion against their policies. The labor

67

Morgan, American Slavery, 296.

33

baron’s goal was to recreate stability in the colony, making sure that Bacon’s Rebellion would

never happen again. They wanted to create a more patriarchal, brutal and racially intensified

slave system. In order to achieve their goal they had a three pronged strategy, this included:

importing more slaves, enacting racially discriminatory laws and giving poor whites more

freedom. The labor barons in Virginia were fashioning a slave society, the same slave society

that plagued America up until the Civil War.

Part I of this essay dealt with the escalation of slavery due to the English Civil War.

Servitude was on the decline because workers were needed in England. During this time period

planters begrudgingly bought slaves. A slave was nearly twice the price of a servant, making it

infeasible for smaller plantation owners to purchase. The reason for the high price of slaves was

Barbados. Barbados originally competed with Virginia in the tobacco market. But, Virginia’s

product was too good for the Barbadians to compete with. Eventually they started planting sugar.

This turned into a highly profitable industry for the Barbadians. Unfortunately, cultivating sugar

was dangerous. Workers on sugar plantations had a high mortality rate. No servant willingly

went to Barbados. It was a death trap. Stories spread of workers’ hands getting caught in the

grinding machines. The overseers would walk next to them and chop their hands off, leaving

them to die. The making of sugar was so brutal that even the English government had second

thoughts about having Englishmen doing such horrid work. Slaves on the other hand had no say

in their destination. They had to do what they were told. To make up for the unwillingness of the

servants, Barbadian planters imported slaves. The cost of the voyage, dealing with the different

African kingdoms, and the demand for those slaves in Barbados caused the price of slaves to

increase. Virginia’s middle and lower classes could not afford those prices. Plantation owners

favored servitude because of its price and it was no indefinite. As mentioned before in Part I

34

planters could work servants to death because they only cared for them throughout their contract,

whereas slaves were there for their life. In the harsh Virginia environment that life could be short

making slavery unprofitable.68

But the trouble with servitude was it created free men. Not everyone who attaints their

freedom reached the social status of Anthony Johnson. Many of the servants and slaves that

became free remained poor. Their plight was the reason they joined Nathanial Bacon. The labor

barons believed that if they could stop the importation of servants then the number of poor white

men would decrease. But changing a labor force does not happen overnight. It was a gradual

process to a full scale slave system.69

The large plantation owners in Virginia started to import most of the slaves. Between

1675 (the eve of Bacon’s Rebellion) and 1695, 3,000 Africans were brought in as slaves. In 1688

white servants outnumber slaves five to one in Virginia’s Middlesex Country. By 1700 that

statistic was reversed. Middlesex Country was not alone in that trend. Other counties in Virginia

had the same phenomenon. Even though some counties saw a boom in slave population, others

still had a much larger white labor force. This trend ended around 1740. In 1720 one quarter of

Virginia’s population was slaves. By 1740, forty percent of the population was slaves. The

majority of these slaves were working on the largest estates. The large plantation owners were

dedicated to bringing in slaves. Although it took them fifty years the labor barons and their

predecessors continued and succeed at switching the labor force.70

68

Morgan, American Slavery, 296-300; Taylor, American Colonies, 206-17.

69

Morgan, American Slavery, 300-304; Berlin, Many Thousands, 109-110; Blackburn, The Making of

New World Slavery, 322-323.

70

Berlin, Many Thousands, 110; Morgan, American Slavery, 295-300.

35

Of course, as demand for slaves went up the supply increased. In the 1680s, 2,000 slaves

were brought to Virginia. By the 1690s that number doubled and the numbers continued to

double all the through the eighteenth century. As large estates started to buy Africans they soon

found it to be more profitable than servitude. Slaves worked for life and even though Virginia’s

original fears of buying slaves were that they would die quickly, it was proven to be untrue.

Because slaves worked a life time labor costs were kept low, thus, maximizing profits. As the

large plantation owners escalated the slave trade more slaves came to Virginia’s ports. This

decreased the amount of servants coming to Virginia. Small farmers were forced to take the high

prices and buy the slaves if they needed new labor. Slowly, servitude was phased out of Virginia

and slavery took control.71

As the importation of slaves increased the slaves’ standard of living decreased. Large

plantation owners were methodical in creating a system of discrimination. For starters, they

started to exclusively import slaves from Africa. Before Bacon’s Rebellion many slaves came

from Barbados or New Spain. They were sold to the Virginias like commodities. But the ones

from Barbados and some of those from New Spain knew English. This allowed them to

assimilate fairly quickly into Virginia’s culture. During Bacon’s Rebellion this proved to be

useful because everyone could communicate with one another. Things could be discussed, away

from the overseer’s watchful eye. In order to guarantee that whites and blacks could not even

communicate with each other slave owners imported Africans. The owners would not stop there.

They also tried to buy salves from multiple African Kingdoms, so the slaves could not even talk

to one another.72

Berlin, Many Thousands, 110-111, Breen, “A Changing Labor Force,” 6-7.

Breen, “A Changing Labor Force,” 6-7, 17; Berlin, Many Thousands, 111-2.

71

72

36

Africans who came to America had to go through the grueling middle passage. Hundreds

of slaves would be piled together in the hull of the boat for weeks on end. Once they arrived in

Virginia they were scared, disorientated and weak. The slave traders wasted no time in stripping

them of their identity. For starters they never sold family members together. This took away any

sort of kinship the Africans might have had. Plantation owners started to give their family name

to the slaves, essentially branding them as their own. Owners then gave typical English first

names, solidifying even more that Africans were no longer connected to the continent from

which they hailed.73 This is why some African—Americans today have English last names.

Malcom Little took the origin of his last name very seriously. That is why he changed his last

name from Little to X, thus rejecting his slave name.

Changing the name of the Africans was only the first injustice. Because Virginia was

increasing the amount of slaves they bought, importation increase and prices started to fall

making slaves easily accessible. Because of this new cheap labor, masters, especially rich ones,

started to treat slaves brutally. If slaves died they could easily be replaced by newer, younger,

cheaper slaves. Slaves were given the worst tasks possible. Doing such backbreaking work

denied them the opportunity to develop skills. In the seventeenth century slaves had the free time

to become great craftsmen, but this new eighteenth century form of slavery deprived them of that

ability. Slaves were given insufficient food, clothing and shelter. This left them week and

vulnerable. Slaves before Bacon’s Rebellion were given all of those things plus free time. That

free time was instrumental in allowing slaves to purchase their own freedom and it gave them

something to hope for. But slavery became oppressive, and hope was gone.74

73

Berlin, Many Thousands, 111-3.

Berlin, Many Thousands, 113-120.

74

37

Before Bacon’s Rebellion slaves were allowed to roam freely. This allowed them to

network with other slaves and masters. The economy with slaves discussed in Part I relied on

slaves being able to travel. This practice benefited both the slaves and the masters because the

owners got the tools they wanted and the slaves received money towards their freedom. But

during Bacon’s Rebellion this roaming caused a lot of problems. Word could travel fast amongst

the slaves that a rebellion was coming. It also allowed them to understand the layout of the land.

If they chose to runaway, slaves would know of places to hide and where to run to. Plantation

owners decided that this freedom needed to go. Laws enacted between 1705 and 1723 limited the

rights of slave travels. In order to leave the plantation a slave needed to have a pass from his

master. It also denied Africans the right to assemble in a group larger than four. This law was

solidified in the slave codes of 1705 which stated,

And also be it enacted, by the authority aforesaid, and it is hereby enacted, That no master,

mistress, or overseer of a family, shall knowingly permit any slave, not belonging to him

or her, to be and remain upon his or her plantation, above four hours at any one time,

without the leave of such slave's master, mistress, or overseer, on penalty of one hundred

and fifty pounds of tobacco to the informer; cognizable by a justice of the peace of the

county wherein such offence shall be committed.75

In order to make sure this law was enforced militia men would go around stopping Africans not

on plantations. This law was created to ensure that slaves could not form a community and could

not organize into a rebellion. They would no longer be able to discuss each other’s plight. Their

plantations became islands. Laws fined slave owners who did not follow these practices. If an

owner allowed a slave to roam freely without a pass the slave would be beaten and the owner

“Primary Resource "An act concerning Servants and Slaves" (1705)” Encyclopedia Virginia, Last

accessed: May 1, 2014,

http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/_An_act_concerning_Servants_and_Slaves_1705.

75

38

would be substantially fined. These laws in particular were created for social control over the

Africans and a guideline for masters.76