a new era for educational assessment

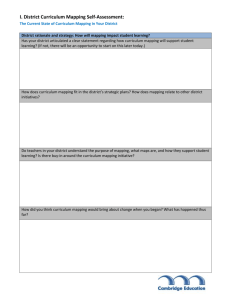

advertisement