1 - Dialnet

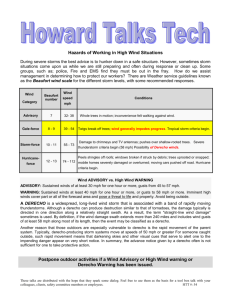

advertisement