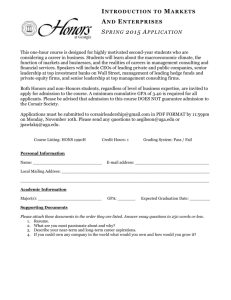

New Mexico Recommendation and Petition

advertisement

2

IN THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE STATE OF NEW MEXICO

3

4

5

6

7

8

RECOMMENDATION AND

PETITION IN SUPPORT OF

AMENDMENTS TO THE RULES

GOVERNING ADMISSION TO

THE BAR OF NEW MEXICO TO

PROVIDE FOR RECIPROCAL

ADMISSION BY MOTION

No. - - - - - - - - - - ­

SUPREME COURT OF NEW MEXICO

FIL.ED

MAY - 2 2013

9

10

11

The New Mexico Board of Bar Examiners (14Board"), an agency of the New

12

Mexico Supreme Court. hereby recommends and petitions the New Mexico

13

Supreme Court to adopt amendments to the New Mexico Rules Governing

14

15

Admission to the Bar (NMRA J5, 101 et seq.), as set forth in the attached proposed

16

rule changes (Tab l). This recommendation and petition follows a special meeting

17

18

19

of the Board on February 21, 2013 during which, by a vote of 7 for and 3 against.

the Board voted to recommend to this Court adoption of reciprocal admission by

motion in New Mexico.

21

22

Background

23

Currently, with the limited exceptions of University of New Mexico Law

24

School faculty (NMRA 15-103), attorneys employed with certain legal services

25

26

1

entities (NMRA 15-301.2, certain public employees (on a temporary basis, pursuant

2

3

4

5

to NMRA 15-301.1), and pro haec vice practitioners, applicants may obtain a license

to practice law in New Mexico by applying for admission, which requires taking and

passing the New Mexico bar examination, successfolty completing character and

6

7

8

9

fitness review, and meeting other requirements. Even lawyers

fmm other

jurisdictions who have successfully practiced law for many years are required to take

and pass the New Mexico bar examination.

10

ll

In contrast with the vast majority of American jurisdictions, attorneys cannot

12

gain admission to practice law in New Mexico by motion or under any form of

13

reciprocity with other states. 20 I 3 Comprehensive Guide to Bar Admission

14

15

16

Requirements (Comprehensive Guide)', Charts l lt 12.

As one result of this situation, New Mexico attorneys applying to practice in

17

18

19

20

other states are prohibited similar access to admission in those states without taking

and passing a bar examination. Mobility of la\l."yers from New Mexico and other

jurisdictions is thereby impaired.

Choice of counsel of clients and prospective

21

22

23

clients is unnecessarily restricted. The reality of transboundary law practice is not

1

served by New Mexico s lack of admission by motion.

24

25

26

2

Following extensive and ongoing study, discussion and contemplation, the

2

Board of Bar Examiners hereby respectfully recommends and petitions this Court to

J

4

5

amend New Mexico's Rules Governing Admission to the Bar (NMRA 15~101 et seq.)

to allow admission by motion with redprocity. Such changes are necessary to meet

6

7

8

the realities of modem law practice and trnnsboundary commerce, serving the

interests of clients, prospective clients, and the members of the New Mexico bar.

9

rn

Changes in New MexicoJs Bar Admission Process are Necessary and Desirable in

Order to Adapt to and Reflect Modern Realities, Including That Law Practice

and Commerce Take Place on an Increasingly Transboundary Basis

12

The anachronistic notion that a local bar examination is necessary to test an

experienced attorney from another American jurisdiction for minimmn legal

15

competence is a relic of a bygone time, which to the extent it persists in tbe 21st

16

17

18

century, exists as a form of economic protectionism for the benefit of lawyers in

those few jurisdictions who continue to adhere to it. This outdated concept is a

19

restriction that serves only " ... to sustain outdated and parochial purposes at a time

21

when the relevance of borders to the competent practice of law has and will

22

continue to erode.u ABA Commission on Ethics 20/20 Report to the House of

23

24

2.5

26

3

Delegates\ p. 5.

2

The evidence demonstrates that considerations of economic protectionism,

3

4

besides being irrelevant; arc not based on fact. Ar, shown in information published

5

in the March, 2013 edition of The Bar Examiner1 at page 26, 27 and 29, adoption of

7

8

9

reciprocal admission by motion does not result in floods of lawyers from other

jurisdictions seeking ta gain reciprocal admission by motion. As well. even without

admission by motion, many lawyers practice in New Mexico without being licensed

10

II

12

in New Mexico, by pro haec vice (Tab 2# information compiled by the State Bar of

New Mexico relating to pw ha.ec vice admissions for the indicated years), in Federal

13

Court (D.N.M. LR-Civ. 83.Zt 83.3 and D.N.M. LR-Cr. 44.1), and by association

14

15

16

with local counsel. Obviously, hrwyers or law firms from outside New Mexico

wishing to practice in Ne\v Mexico can and do find a legal \\.'TI.y to do so without a

17

18

New Mexico law license.

Arguments against motion by admission whether or not grounded solely on

19

20

considerations of economic self.interest1 may be advanced by la·wyers who may feel

21

22

23

24

25

26

\YMV ,umcrka1ul1ar .org.h:::s;in~P rLdumLaba/admi11is1:rath~t\:s.

2

. 1l~~MlQ5t;.J}kL1u1y 2011.n!,tthcheGk~i114Il1;lf

3

~~w\Y,.r:u;.bg~>!Lm/.J:tli~~.rsimed itt fU es/13ar;:

J;i,•$.JiJ'.!llniw11.'.ru:tb;:1~2 \lt1:a 2.Q 113abridged. pdf

4

ZQMf:.0/2QJ)M hmLn

threatened by the prospecc of other, experienced attorneys becoming licensed in

2

New Mexico without having to "run the gauntlet" of a bar examination. But the

3

4

5

Board's role is not to protect, or continue protection of, New Mexico attorneys from

competition, real or imagined. Rather, the Board's j<)b is focused on protecting the

6

7

8

9

public, including legal consumers, by ensuring that those who are granted a license

to practice law in New Mexico are qualified

by education, knowledge, character and

fitness to do so.

10

11

12

Requiring experienced lawyers from other American jurisdictions, who have

sound discipli.naiy 1 character and fitness records, to take a bar examination to

13

demonstrate minimum legal competence is wholly at odds with appropriate rule.

14

15

making regarding regulation of the legal profession. A~ this Court has stated,

16

••... !t]he [legal! profession has a responsibility to assure that its regulations are

17

HI

19

20

conceived in the public interest and not in furtherance of parochial or self~interested

concerns of the bar. t (Citations omitted). Ro)' D. Mercer, LLC v. Gandy Dancer, LLC~

1

2013#NMSG002 (2012).

21

22

A.

New Mexico Should Join the lvfojority of ..A..merican Jurisdictions and

Adopt Admission by Motion

23

24

Admission by motion with or without reciprocity has been adopted in most

25

26

5

United States jurisdictions, leaving New Mexico as an outlier in this respect.

2

Comprehensive Guide, Charts 1 l, 12. This overwhelming trend towards admission

3

4

5

by motion responds to the reality that local bar examinations are both unnecessary

and irrelevant to determine minimum required legal competence of experienced

6

7

8

attorneys\ as well as to client, professional and personal interests and demands for

national, regional and other transhoundary access to legal services.

9

ll

12

In August1 2012, th.e American Bar Assodati.on (ABA) House of Delegates,

approved revisions to the ABA Model Rule on Admission by Motion. 5 Reference is

made to the ABA's studies and publications which are cited herein, as well as to

other literature concerning admission by motion, including those articles attached as

14

15

Tab 3.

16

There is no point in rehashing or reiterating the ABA's research into the

17

18

19

benefits of multijurisdictional prnctket including admission by motion as a primary

catalyst. Nor is chere benefit in parroting the many commentaries on this subject.

20

21

22

+ See e.g., Ke Kanawai Mamalahoe: Equalicy in Our Splintered Pwfession, 3.3 U. Haw.

23

5

24

25

Law Rev. 249 (2010).

·

· · Jt'l)l}~111.!:' l,,)Lt l!'.j14~.

· 1~.\\/.~~· ltJJUJ.l!iS~J)l}

' .

\

'$!j"/):'j !.l!JJll~rJSlIJL'.1.Ul

' 1< !.l'hU fil5}J!Jl;lj/ nrP..fe§.~JJUlIL.

.. <;:.tJ

l

· "

· '

I·

·1

1

""""'~,x.•.: .. lQ!htm1 and

~-~:.1Jlmsc:):l~:a11l1ux,&u.1:w.J;m1!&11 tidu n1b:iJ1~1Ll,~J rrJJ1ustrn t h•d_s;JJ11~~.li.-i~UQLi~l11JJ:IBI fl

JlllUaLm.x:~tlllLLlQilk· fH~d 1.miy 2012.:mrbrh~~ckd;un.pdi

26

6

The reasons to adopt reciprocal admission by motion are not only well documented,

2

they can be said to be self-evident.

3

In general; the Board endorses the ABA\; reasonit1g with regard to admission

5

by motion. Hmvever, as discussed below, the Board diverges with the ABA In that

6

7

8

9

the Board recommends admission by motion on a reciprocal basis, rather than on a

totally open basis. Also as discussed below, the Board's recommended rule changes

relating to admission by motion differ from the ABA's model rule in other respects,

JO

including tightening definitions of qualification criteria.

12

B. The Proposed Rules Changes Will Better Serve and Protect Clients of

13

Lawyers Admitted to Practice in New Mexico

14

Providing for admission by motion would enable clients to benefit from access

15

to

a wider range of attorneys.

Further, admission. by motion would also enable

16

clients to continue to utilize their counsel of choice, including New Mexico

18

attorneys, across state lines as the need arises.

19

20

21

22

The proposed rules changes are designed to continue to protect, through

quality control criteria, clients of New Mexico lawyers, including those lawyers

admitted by motion. Applicants for admission by motion must have earned a lavv'

23

24

degree from an ABA-accredited law school and have passed the Multi.state

25

Professional Responsibility Examination with the

26

7

designated

scaled score.

Additionally1 applicants for admission by motion must have engaged in the active

2

practice of law for five (5) of the prior seven (7) years in a reciprocal jurisdiction;

3

4

5

successfully meet New Mexico's character and fitness and other qualificadons6; and

be in good standing in the subject reciprocal jurisdktion(s), without any pending

6

7

disciplinary complaints.

Supported by research and common sense, the Board is of the opinion that a

8

9

qualifying record of active law practice without disqualifying disciplinary or other

IO

character and fitness issues, is without: doubt more compelling evidence of at least

12

minimum required legal competency than is a bar ex.'lmination.. This point bears

13

special emphasis in consideration of New Mexico's comparatively quite modest bar

14

15

examination grading and scoring requirements (Comprehensive Guide, Chart 9),

16

combined with New MexictJ's current essay grading paradigm which is based on

17

18

issue~spotting but does not add value for demonstrated analytical ability.

With the exception of Community Property law, examinees currently are not

19

20

required to demoastrate specific familiarity with New Mexico law in response to

21

22

essay questions. This fact further calls into question any reason for experienced

23

24

6

25

This is in favorable comparison with pro haec vice admission

wherein there in no character and fitness evaluation.

26

8

In New Mexico,

attorneys to be required to sit for the bar examination. Moreover, the proposed rules

2

changes require that every applicant for admission by motion, prior to

4

5

recommendation for admission, attend and verify attendance at and completion of a

course on Indian Law and New Mexico Community Property Law. With this added

6

7

8

9

proposed requirement, the need for familiarity with both Indian Law (which is

principally Federal law) and New Mexico Community Property Law ls addressed,

likely in a more effective and lasting manner than would the possibility of having to

10

1I

12

13

14

answer an occasional bar examination that may touch on one of these subjects.

c.

The Proposed Rules Changes Are in the Public Jnterest, Affording New

Mexico Attorneys and Thei.r Clients Reciprocal Benefits

It is beyond cavil that law practice is a transboundary reality, as are other

15

16

J7

18

professional practices such as medicine and accounting. Commerce in general is

increasingly less governed by political boundaries.

The proposed rules changes

reflect modern realities. New Mexico attorneys would be able to continue to serve

19

20

their clients in reciprocal jurisdictions, and their clients would be able to continue

21

with representation by their choice of counsel.

As well, 2 l 't century society is increasingly mobile. For example, should the

23

24

25

need arise to move to another jurisdiction due

to

a partner's .or spouse's transfer, a

New Mexico attorney may need to become licensed to practice law in one or more

26

9

additional jurisdictions. Such a sinrntion may arise with particular frequency or

2

urgency if the attorney's partner or spouse is a member of the military7 • Preparing

3

4

for and travelling to take a bar examination in another jurisdiction is obviously a

5

time-consuming effort, which may be impractical and will always result in significant

6

7

8

9

delay and expense.

AB previously noted1 it is not diftlcult for lawyers who are not licensed in New

Mexico but who are licensed elsewhere to nonetheless practice law in New Mexico.

10

It

12

See pp. 1-2, 4. Admission by motion, unlike other methods currently available to

out;.of-state practitioners to practice law in New Mexico, will require applicants to

13

meet rigorously defined quality control criteria, including character and fitness

14

15

vetting. Such is dearly in the public's interest1 as well as in the interest of the courts

16

and the bar in general. lt is difficult if not impossible to reconcile the current

17

18

19

20

acceptance of various mear1s by which out-of--state lawyers can practice law in New

Mexico without a New Mexico law license, with objections to admission on motion.

Next, attention is to be paid to the principle of reciprocity. The proposed

21

22

23

24

25

26

10

rules changes, if adopted, would allow New Mexico attorneys reciprocal

2

opportunities to become admitted in numerous other jurisdictions without having

3

4

to sit for a bar examination and thereby facilitate New Mexico attorneys, ability to

5

represent clients and compete both regionally and nationally, move to 0th.er

6

7

8

9

jurisdktions1 recruit new lawyers; and otherwise benefit from an increased ability to

practice on a transboundary basis. In other words, New Mexico lawyers stand to

gain at least the same benefits from reciprocal admission by motion as those

10

ll

12

13

attorneys who may choose to seek admission by motion in New Mexico, It is

unsurprising that surveys of New Mexico bar membership show that a majority of

New Mexico licensed attorneys support reciprocal motion by admission. Tabs 4 and

14

15

16

5.

We are informed that Tub 4 is a 2004 Membership survey, and that it was

17

1

mailed to all active members with results posted on the Bar s website. See question

18

19

20

7 3 on page

5 thereof. We are also informed that the critkism received regarding

this question was that a follow up question was not asked about support; only

21

22

23

24

whether members thought it was important. 69% thought it was very important or

important. That criticism appears to have been adequately addressed by the

relevant questions asked in a 2011 Membership survey (Tab 5) which was also

25

26

11

mailed to all active members. See page 5 of Tab 5 for questions about reciprocity

2

and tJro haec vice. We are informed that these data \Vere also published on the Bar's

3

website.

5

D. Lawyers Admitted Elsewhere Can and Do Practice Law h1

New Mexico Whether or not Being Licensed

6

7

We have already noted how at present and through various legitimate means,

8

9

10

11

lawyers who are admitted elsewhere but not in New Mexico can nonetheless practi.ce

law in New Mexico. Even so, the bar examination is not necessarily a deterrent to

those attorneys from other jurisdictions who seek admission to prnctke in New

12

13

14

Mexico.

It is empirically established that attorneys from other jurisdictions,

including highly experienced attorneys, will sit for the bar examination in order to

15

become licensed in New Mexico. For examplet 86 of the 148 applicants who sat for

16

17

18

the February 2013 New Mexico bar examination are admitted in at least one other

jurisdiction. 16 other applicants were admitted to practice elsewhere, but chose to

19

20

21

22

defer taking the exam. Of the 86 attorney-applicants who sat for the bar exam, 54

indicated that they have been licensed to practice law since 2008 or earlier, and 8

indicated that they had bee11 licensed since 2009. 12 of the 16 attorney applicants

23

24

who chose to defer taking the examination had been licensed since 2008 or earlier.

25

lt is noteworthy that only 2 licensed attorneys of the 86 licensed attorneys who sat

26

12

for the Febrnary, 2013 New Mexico bar examination failed it. This is consistent with

2

the 95% pass rate by firsHime takers of this most recent New Mexico bat

3

4

5

examination. All of the above serves to underscore why most jurisdictions have

abandoned a bar examination requirement for experienced lawyers licensed

6

7

elsewhere.

Evidently, attorneys do not seek admission on motion simply because it is

9

available, nor do they seek reciprocal admission on motion in large numbers where

10

such admission is available. The Bar Examiner, March, 2013, pp. 26 1 27 1 2911• The

12

fact is that being an active member of the bar requires financial obligations,

l3

continuing legal education, and other commitments that mean reciprocal admission

14

15

by motion is unlikely to be sought on a whim.

16

II.

Admission to

17

18

With regard to the drafting of the recommended rules changes~ a number of

19

20

other jurisdictions' rules regarding admission on motion were reviewedt as was the

21

22

ABA's Model Rule on Admission by Motion.

23

24

8

25

j;\tww.i:u::l;srx.ori:/asset&/mh:dia flies/Bar·

~~~1.Attdi;'..sLlO J.3/820113ahridttt·d.pd f

26

lJ

As well, relevant case law was

considered. Ultimately, the proposed rules changes borrow most heavily from the

2

ABA Model Rule and Arizona)s Rule.

3

4

The ABA Model Rule does not contain a redprodcy requirement, and the

5

ABA counsels against such. The Arizona Rule is reciprocal, as is the case with most

6

7

8

9

jurisdictions which have adopted admission by motion.

Comprehensive Guide,

Charts 1 L 12. Contrary to the ABA's viewt but consistent with the majority of

admission~by·motion

1

jurisdictions, it is the Board s view that reciprocity is an

10

11

12

important part of a fair admission by motion process. A New Mexico attorney

should be afforded the same opportunity and ability to secure admission to practice

13

law in other jurisdictions as attorneys from such jurisdictions who seek the

14

15

opportunity to become licensed in New Mexico. Correspondingly, clients of New

16

Mexico lawyers should benefit from being able to continue with their counsel of

17

18

l.9

20

choice should they have need of legal representation in other (reciprocal)

jurisdictions; just as would clients of lawyers from reciprocal jurisdictions who seek

admittance to practice law in New Mexico. "To secure for her citizens the reciprocal

21

22

23

right'i and advantages obtained under such [professional licensing] statutes or rules is

manifestly a legitimate interest and goal on the part of a state just as it is a legitimate

24

interest of one nation to secure reciprocal property rights for its citizens in other

25

26

14

nations.... Reciprocal statutes or regulations, it has been uniformly held} are

2

designed to meet a legitimate state g()al and are related to a legitimate state interest."

3

4

5

7

8

Hawkins v. Moss, 503 F.2d 1171,

1177~78

(4 1h Ch:. 1974). cert. denied 420 U.S. 928

(1975). See afao, Gold.smith v. Pringle, .399 F.Supp. 6ZO (D. Colo, 1975); In re Conner1

917 A.2d 442, 450451 (Vermont 2006) icmd Spencer v. Utah State Bar, 293 PJd 360

(Utah 2012)9• See also discussion at Annot.• 14 A.LR.

4th

7

9

The fee required for admission on motion can and should be set at an

10

ll

amount substantially higher than the cost to take the bar examination. As shown in

12

the Comprehensive Guide, Chart 11, jurisdictions whkb have adopted admission by

motion have established a substantial application fee.

14

The Board recommends a non-refundable applicat[on fee of $2.500.

15

16

]ustifications for this fee include 1) processing of additional applications, including

17

18

19

20

but not limited to ferreting out potential character and fitness issues is ti.me~

consuming and expensive; 2) the suggested fee will assist i.n defraying the ever..

increasing costs of character and fitness investigations, hearings and other

21

22

23

24

25

9

The constitutionality of Arizona's reciprocity requirement is currently the subject

of litigation. National Association fo1 the Advancement of Multijurisdictional Practice et

aL v. Hon. Rebecca White B1.trch, et al., CVlZ.01724, United States District Court for

the District of Arizona,

26

15

proceedings; 3) in comparison with costs an applicant would incur in preparing and

2

sitting for a bar examination, the suggested fee is modest; and 4) as with pro haec vice

3

4

5

foes, a portkm of the admission on motion application fees can and should be used

to assist funding Ne\v Mexico's Access to Justice Grant Committee, thus ensuring

6

7

&

9

that applicants who apply for admission on motion contribute to the public good.

CONCLUSION

This recommendation and petition proposes an additional path for admission

10

11

12

to practice law in New Mexico. This is a matter of importance not only to this Court

and the Board, but certainly t<) the public and the bar. The Board recommends that

13

prior to taking action on this recommendation and petition, the Supreme Court 1)

14

15

!6

cause to be published the proposed rule amendments in the New Mexko Bar

Bulletin, on the State Bar's website, and such other and further publications and

17

l8

19

20

locations as the Court deems appropriate; 2) provide a period of comment from the

public, the bar and other interested parties; and 3) provide an opportunity for the

Board to respond to such comments. Meanwhile, the Board proposes to circulate

21

22

the draft rules changes to other jurisdictions, to ensure that if this Court adopts the

23

proposed rules changes, potential reciprocal jurisdictions would grant qualified New

24

Mexi.co attorneys reciprocal admission on motion. Thereafter, the Board respectfully

25

26

16

requests that the Supreme Court order adoption and implementation of reciprocal

2

admission by motion in New Mexico.

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

IQ

u

Respectfully submitted on

Behalf of the Board of Bar Examiners

s

Howard R. Thomas

Chair, New Me.xico Board of Bar Examiners

May 2, 2013

12

14

15

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

17

TAB3

'

~

SlATEBAR

of

NEW MEXICO

Reciprocity

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ON RECIPROCITY

Law students Daniel Marquez and Patrick Redmond. under the supervision of University of

New Mexico Law Librarians Barbara Lah and Alexandra Siek, researched the issue of reciprocity and

bar membership. This is a short summary of the memorandum discussing the findings of thnt resenrch.

CoHectiveJy the memos discuss the following issues raised by reciprocity: l) the vnrious forms of

reciprocal licensing schemes: 2) the impact that reciprocal licensing has had on bar membership~ 3) a

comparison of reciprocal licensing to admission pro hac vice; 4) legal issues such as constitutional

concerns raised by the adoption or rejection of reciprocity; and 5) professional issues.

Before delving into these topics and the arguments for and against reciprocity h is important to

become famiJiar with the history of professional regulation, reciprocal licensing, and the development

of restrictions on interstate practice, Until the em of the Great Depression, reciprocal licensing under

admission on motion was the rule rather than the ex.ception. 1 During the latter half of the twentieth

century, however. as improved transportution and communications facilitated multijurlsdictional

practice. some states reacted by repealing their reciproca] admission rules. 2 After a 1998 case stirred

the waters3, the American Bar Association created a Commission on Multijurisdictional Practice, which

resulted in a model rule for admission on motion, designed to ease impediments to attomeys• national

mobility. 4 Some states followed with new rules for reciprocal licensing, admission on motion nnd

admission without examination, 5

Critics of multljurisdktiona1 practice reform remain, however. Some have raised states' rights

and inherent powers concerns. 6 Others have argued that argued that "state licensing assures quality

control among Jawyers and protects clients from incompetent practitioners."7 Still others have cast

multijurisdictional prnctice refomi as part of a trend toward encroachment on the legitimate practice of

law by non-lawyers. Proponents of reform have answered that state Ucen.-;ing and regulation would

continue under the ABA proposal. Further. a larger pool of specialized practitioners would more likely

tmhance than detract frotn the quality of legal services in the .state. 8 Refonn ~ponents have suggested

Uuu opponents' real motive for retaining barriers is economic protectiouism. Even the U,S. Supreme

Court has repeated the comment that many states that have "erected fences against ouN>f-state lawyers

have done so primarily to protect their own lawyers from professional competition.'' 10 Apart f:rom

practical nnd professional issues. state harriers to multijurisdictioual practice would seem to be

disfavored under the Article IV Privileges and Immunities Clause. the Fourteenth Amendment

Privileges and lmmunities Clause and the dormant Commerce Clause, among other provisions.

To be clear, the basic idea behind reciprocity is that the foreign attorney is granted fu!J

admission and licensure with the forum st.ate bar associarion without having to take that state's bar

'RICHARD L :\rHi'l, AMI:.RK.M> LAIVYLRS J J 5·1!:\119891.

: .Set', t>.g.. M!cliaef P. Crow. /,f Nrcfpl'tk'ily Making a Comebru:k?. 73 J. KAN. B. A5s's -'!Oct, 1()04).

' Simo\\ ct v, Superior Cmm of Sant.a Clam Coutlt). 9+9 f' Zd I (Cal. l•Nl:!),

'MJA Model Rule an Admi.uimr h.V Jlmim1. ti.u.iii.tbft: at litt12·.dw" 1~,iJh;im.'!.11~ij\nrtm;rJfrnul !1JIP rp! !217n:tpdi; ld. at 50.

" Sec Mwrlc fanscn, .UJP Pick,: Up Sr<'<rm: More> Srrues ~rt' l.1.wJki11g ill ALM Propo.rofs w Emw kufes 011 M11!1ijuristficlioool Prtrc1ice. 90

,.UtA. J. 43. -is clan. 2004).

~Set' Gary A. ,\ftunncke. MrfftijuYisdit'rit1m;1J Prat:Jice ojlnl•·: R«wrt Dewdopnumls in 1fie 1'/(1Jf<>nal Debatr, 27 1 Lf:VAI. PROF. 91, !06

t20lll!.

fd.

'ld. at !07.

• !tl.

r•> Supreme Coun: ot' New llampshirc v. riper. -tW t:.S. 214, J~5 ( 198:5) cqooting.Smit.h, Timejiira Nari/ma! Pn:tNit·e of Law Aa. 64

A.B.A.J. S57 (l'f/lij).

.

examination. But the requirements for such admission differ from state to state. It is helpful to identify

the different licensing schemes in the following manner.

There are basically three licensing methods in use labeled "general reciprocity," "limited

reciprocity," and "strict reciprocity." 11 "General reciprocity" is the most open and flexible form of

reciprocal licensing. Normally any qualified attorney from any state is ;ranted bar admission in a

•·general reciprocity" jurisdiction. Texas 12 and the District of Columbia 3 employ "general reciprocity:·

"Limited reciprocity" is the intennediate form of reciprocal licensing. Under this system only

attorneys from jurisdictions that would extend a reciprocal license to an attorney from the granting state

may receive reciprocal admission. Colorado 14 and Alaska 15 are "'limited reciprocity'' jurisdictions .

..Strict/Specific reciprocity" is the most restrictive form of reciprocal licensing. A "strict/specific

jurisdiction" will only offer reciprocal licenses to attorneys from specific states. Maine 16 has a

«strict/specific reciprocity" agreement with New Hampshire and Vermont. Depending on the state its

reciprocal licensing scheme may have been in place for decades or perhaps only a few years.

The next issue covers what effect, if any, the existence or adoption of reciprocity in a state had

on bar membership and admission by examination. Extensive research in this area found no oouclusive

or correlative evidence that suggested the adoption of reciprocity attracts inordinate numbers of out-of­

state attorneys or appreciably reduces the number of applicants sitting for examination. A blanket

conclusion that the adoption ofreciprocity, especially an expruisive form like "general reciprocity," has

no cffec.t on bar admission numbers, even initially, may not be entirely warranted. The District of

Columbia's adoption of reciprocity produced an initial decline in admissions by examination of almost

60%. 17 In other uniquely attractive states or those bordering states with very large bar memberships

such as Califomia, Florida, New Jersey. Nevada. Arizona and even New hiex:.ico. any hypothesis

remains untested, since they have not }'et adopted reciprocity. It does seem that once reciprocity has

been in place for a number of years bnr admission numbers resist fluctuation and revert back to steady

and predictable figures. This has been the case in the District of Columbia, Indiana. Iowa.

Massachusetts, Michigan, and Minnesota. 18

In developing the classification of reciprocal licensing schemes it was important to note that

admission pro liac vice is not the same as nor 1s it a fonn of reciprocity. The major distinction is that a

reciprocal license grants the licensee full, unencumbered membership into that State bar. Admission

pro hac vice does not grant an attorney a license to practice law in that state. Admission pro hac vice

ortly pennits certain court appearances. usually only applies to litigators, and usually limits the number

of appearances fill attorney will be granted per year. Further pro hac vice rules usually do not provide

the same protections that most reciprocity ntles do such as a minimum number-of-years practicing

11

These are labels which were developed by O.iniel Marquez and Patrick Redmond.

l 2 RULES GOVER~t'\'.Q ADMISSlON TO THE BAR Of' TEXAS RULE .XllI.

IJ D.C Ct. ..\PP. Rl'LF.46(c)[3}.

14 C. R, C. P. 2t}Ul I).

I :i r\K. BAR R.1.

l6 MAfNEBAAADMINJSTR..\TlO:-.i RULES I IA.

t

~ E-muil from Christopher C. Dix, Deputy Director Co mmillce on Admissions for the District of Columbia Bar 1March

7th, 2007. 7;04 .At'\4 MST).

ts Compare Natfonal O.:mference of Bar faamiaers. J989 STATISTICS 9 ( 19.89)

hllllll\\ '""' ,nd1..:... .r1rg!ijlerM1IJlilY'ms:s!i;1[il!t~Atli...-q;ln;1di./B;1r .-\dmi...~i•jn,f! 9S'tili.l\-",~Nff. muJ NatfoMI Cunteren~e cf 8:ir

E,xumincn>. 1996 STATfST!CS 2.J ( 1996J

h up:l/www. m;hc3,<,1t21 ii !c.udminimegiat!l~slgt'w nhtdslf:far ,;\&lrnlss inMf I996sflltS.J2Qf, aud National Cnn ferell\,.'t of Bar

Examiner&. 2005 STATIS1'1CS J;4 {:!005)

http ;l/www. n..:bcx.on~lli ls;admifllmed iu liksldti wn lo adli!Bar Admissi<l1Jl!/2f,MJ5sml§ ,pdf.

2

requirement or the maintenance of an in-state presence requirement. Finally. because reciprocal

licensees are licensed bar members it is easier to assert disciplinary authority over them than unlicensed

attorneys appearing temporarily under pro hac vice rules

The substantive argwnents for and against reciprocity are separated into two categories-those

based on legal issues and those based on professional issues. The n1ost common professional issues

discussed are economic protectionism, cJient autonomy, attorney competence, protection of local court

systems, and attorney discipline. Although rarely admitted by the opponents of refomi. many

commentators, judges, and lawyers identify economic protectionism as the main reason for the

rejection of reciprocity. 19 In fact those states with the largest legal e<:onomies or their neighbors such

as California, Florida. Nevada, Arizona, New Jersey and New Mexico have refused to adopt

reciprocity.

Another argument made to advance reciprocity is that clients are better suited to choose their

legal representatives and should have the freedom to do so.w This may be true for sophisticated and

experienced legal consumers such as large corporations. The reverse argument is that the entire point

of the licensing process is to test attorney competence, ensure client protection. and preve1lt

professional misconduct. .But no evidence or empirical data could be found to impport the argument

that foreign attorneys engage in professional misconduct more frequently or are less competent to

practice law. 21 Additionally, others argue that foreign attomeys have less of a stake in the community.

There is less of an incentive for the foreign attorney ro obtain justice, offer pro bone services,

participate in local continuing legal education, or pursue legal actions or attempt to establish preccdent

which will benefit the community.22 Others have raised concerns ab<:mt :momey djscipliue. It is not

entirely dear how expansive a bar's jurisdictional authority is. Even if disciplinary jurisdiction ex.ists

the resources to discipline out-of-state attorners may not. This concern has been expressed by both the

smallest and largest legal systems in the U.S. 2 And aside from discipline, questions about the civil and

criminal liability of these attorneys also remain unclear.

As for the legal issues raised by reciprocity under the Constitution's anti~protectionist provisions. a

review of case law and commentary compels a curious conclusion. While courts have noted the

burdens intentionally placed on out-of-state competition, for the most part these butdens do not appear

to be constitucionally vulnerable. TI1e practice of law is a constitutionally protected privUege24 • and a

residency requirement for bar admission violates. Article lV's Privileges and Immunities Cfa:us:e.25 The

Supreme Court has suggested, however, that some ruurowlydtaiiored "indicium of commitment"

iv See, e.g., Andrew M. Perlman, A Bar Againsr Competition: The Unco11.stitr11ionality ofAdmission Rules for 0111-ofstme

Lawyers. 18 Geo. J, LOOAL ETHICS 135, 147-48; Gerald J. Clark. The Two Faces of,\<Julri-Jnrisdict1<mal Pra,·tfce, 29 N.

Ky, L REV. 251. 265 £2002); Supreme Court of New Hampshire v, Plix-r. 470 U.S. 274. 285 n.18 (1985), qrmted ir1

. Perfmanat 150: Clim Bolick. The Arizona Bar: Not Exactly a Warm Wdcome, 39 ARlZ NIT'Y 34 ft\pr. 2003).

JJ

Cu.. St!f'REME COURT ADVISORY T,\SK foRCE ON MlJLTJJCRISDICTIONALPRACTICE, fJNAL~PORT AM)

RECOMMENDAr JONS 2 l i 2002). ava iiable m lurp:Nww w..:m1t! i nfi1,i,;a. t?o kJ'rcfcr~!J:i;£/dn.;umcnty'itnnlmirrt-pt .n(,!1) f [;m

visi1cd Mav 8, 2001).

'

•'I See. t!.g.. Carol

A. Neei.lh.acn. ,Huliijurisdirtfrmt1l Pmcri<:c· Regulmimu Gm·emfng Attorneys Cm1duc·ti11g a Tnmsacrimwl

PmctiCI!. 5 U. tu... L. l\BV. 1331 f 2003); Perlman. suprn note 19, nt 171.

11

Piper, .rJO U.S. at 285: See alw A.KA. Center for Professional Responsibifit)'. Client Represe11tatimr in tile 1 lsr

Centruy. 2002 A.B.A. REPORT OF THE COMMISSION ON MULTIJURISDlCT!ONAL PRACTICE !Aug. 12.

:?002), arniiabte df !Jlt11;Jfwww.-0bancr.r•q;i..:pr/mjp1tinal mip !'.Pt ! 2 l702,pgJ.

:i St!e. e.g.• DEL. STATE BAR ASS' N, REPORT OF THE MllLTJJlJ!l:ISDICflOS' AL PRACTICE SPE:tr,\l. COMM. 19 (20<H ): CAL.

24

l$

SlJPRE"1E Coun A ovrso~ y TASK FORCE ON MULT!Jt.:!USDICTIONAI. PRACTICE. supra

Pipt~r. 470 U.S. at 2l«J.R l.

Id. llt 288.

3

nore 20. al

.

19.

requirement may be permissible under the Clause.26 A bar examination requirement serves as such an

"indicium of the nonresident's commitment to the bar and to the State's legal profossion. 'm It i$

questionable, however. whether the "intention to prnedce.. requirements many states impose

demonstrate a compa.11lble "commitment" so much as they resemble invalid residency requirements in

bearing only a supelficial relation to it. Nor do bar examinntion requirements seem likely to run afoul

of Fourteenth Amendment Privileges or Immunities. Despite a recent District Court declaration that

"limited" reciprocity violates the •·right to travd/' 28the prevailing view seems to be that requiring out­

1

of~state attorneys to pass the bar exam cannot constitute prohibited ..differential treatment." ~ For

purposes of Dormant Commerce Clause analysis, restrictions on out-of-state lawyers at least arguably

affect interstate commercial activities. 30 However. courts are unlike) y to doom a bar examination

requirement as unconstitutionally burdensome or discriminatory, since most in-state attorneys have in

fact fulfilled it. 3 ~ As some commentators might say. states can continue to pursue largely protectionist

policies with apparently fun constitutional sanction.

:~Supreme

~'Id.

CmutofVrrginia v, Friedman, 4&7 U.S.59. 68 (1988}.

2~

Morrison v. Board vfLaw Examiners of North Carolina, 360 F. Supp. 2d 7.SL 759 (ED.N.C. :!005}, rev'J,453 FJd 190,

1:+th Cir. 2006), ct'n denied 127 S.CL 1124 (20071 i Nme tnat rhis decision was later reven;ed.)

:<i St't'. r!.g.. Padulan v. Ororge. 2'.!9 F.3d 1:!26. 1229 i9Ht Cir. 2(l(l0t

•Ll Crmnnem. Com11wn.·r Clause Cfrc1ll1mgr IJ'J SUJt<' Resuicrlons mr Pmnice by Our-<if-Swte Attem1eys, 72 NW U. L Rf.V.

1Ji'. 7400978).

1

' Scariano v. Justkcs ufthe Supreme Cnurtoflndian.a. 38 F.3d 920. 927 t7th Cir. 1994).

4