Business models for product life extension - Aalto

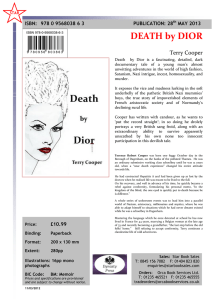

advertisement