Rutgers Journal of Law & Public Policy - Williams Institute

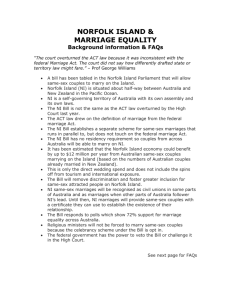

advertisement