►

►

►

►

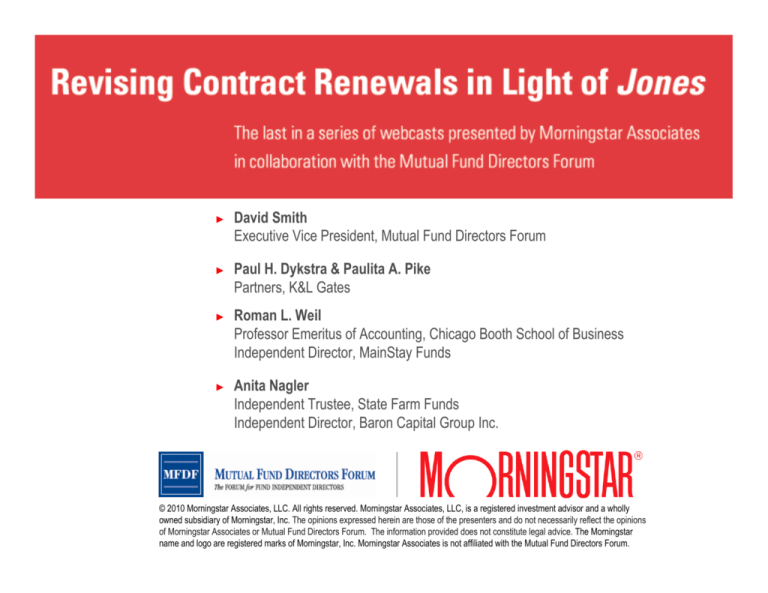

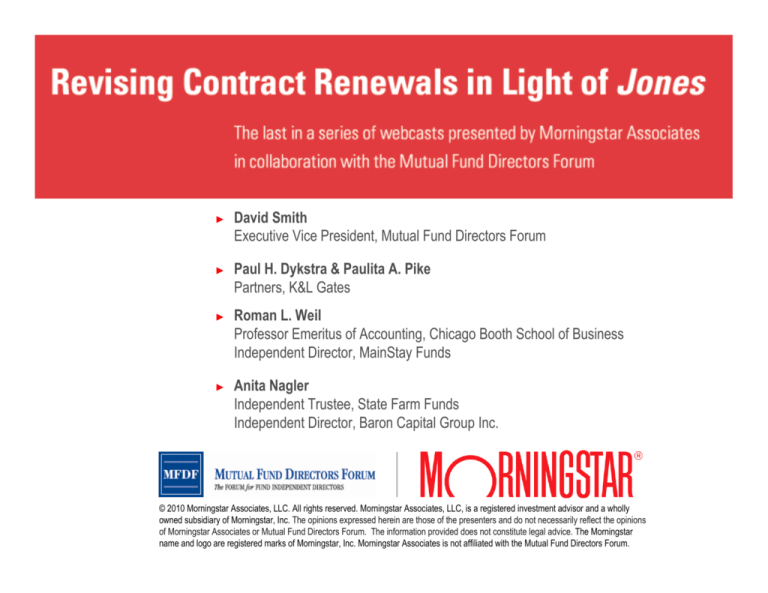

David Smith

Executive Vice President, Mutual Fund Directors Forum

Paul H. Dykstra & Paulita A. Pike

Partners, K&L Gates

Roman L. Weil

Professor Emeritus of Accounting, Chicago Booth School of Business

Independent Director, MainStay Funds

Anita Nagler

Independent Trustee, State Farm Funds

Independent Director, Baron Capital Group Inc.

© 2010 Morningstar Associates, LLC. All rights reserved. Morningstar Associates, LLC, is a registered investment advisor and a wholly

owned subsidiary of Morningstar, Inc. The opinions expressed herein are those of the presenters and do not necessarily reflect the opinions

of Morningstar Associates or Mutual Fund Directors Forum. The information provided does not constitute legal advice. The Morningstar

name and logo are registered marks of Morningstar, Inc. Morningstar Associates is not affiliated with the Mutual Fund Directors Forum.

David Smith

Executive Vice President, Mutual Fund Directors Forum

2

Paul H. Dykstra & Paulita A. Pike

Partners, K&L Gates

3

The Decision

►

On March 30, 2010, the Supreme Court issued its highly anticipated decision in Jones v.

Harris Associates, L.P.

►

►

The decision resolves the Circuit split that was created when the Seventh Circuit Court

of Appeals adopted a new, market-based standard for the evaluation of investment

advisory fees under Section 36(b) of the Investment Company Act of 1940.

In a unanimous opinion, the Court concluded that the Second Circuit’s 1982 decision

in Gartenberg “was correct in its basic formulation of what Section 36(b) requires: to

face liability under Section 36(b), an investment adviser must charge a fee that is so

disproportionately large that it bears no reasonable relationship to the services

rendered and could not have been the product of arm’s length bargaining.”

4

Section 36(b) of the 1940 Act

►

Section 36(b) imposes a fiduciary duty on mutual fund advisers with respect to their fees and

authorizes civil actions by the SEC and shareholders for breach of that duty.

►

In Jones, the plaintiffs alleged that fees the adviser charged to the Oakmark Funds were

excessive as compared to fees charged to its institutional clients.

►

The Jones plaintiffs leavened their complaint with allegations that the fee approval

process has been tainted by the presence of directors who were not truly “independent.”

►

The district court, applying Gartenberg and finding that the independent directors met

required independence standards, granted the defendant adviser’s motion for summary

judgment.

►

The plaintiffs appealed, claiming in part that Gartenberg incorrectly interpreted

Section 36(b).

►

The Seventh Circuit affirmed the district court’s grant of summary judgment, but

disapproved of Gartenberg.

5

Judicial Split Among Circuits

►

For over 25 years, Gartenberg served as the predominant framework for judicial and

regulatory interpretations of Section 36(b) and functioned as the nucleus of fund boards’

annual review of investment advisory contracts under Section 15(c) of the Act.

►

Departing from this precedent, Chief Judge Frank Easterbrook wrote for the Seventh Circuit in

Jones that as long as a fiduciary, such as a fund’s adviser, “makes[s] full disclosure and

play[s] no tricks,” that fiduciary generally is free to negotiate its compensation in its own

interest, like any other market participant.

►

Observing that the fiduciary duty standard in Section 36(b) “differs from rate regulation,”

the Seventh Circuit concluded that the statute did not require that advisory fees be

“reasonable” in relation to a “judicially created standard” like that articulated in

Gartenberg.

►

Although the Seventh Circuit acknowledged that it was “possible to imagine

compensation so unusual that a court will infer that deceit must have occurred, or that

the persons responsible for the decision have abdicated” their responsibility, that was

not the case where, as in Jones, fees “are roughly the same…as those that other funds

of similar size and investment goals pay their advisers.”

6

Judicial Split Among Circuits (cont.)

►

The Circuit split created by Jones caused Judge Richard Posner, in a vigorous dissent from

the denial of rehearing by the full Seventh Circuit, to question the substantive standard

required by Section 36(b).

►

According to Judge Posner, the “economic analysis” underlying the panel decision’s

rejection of Gartenberg was “ripe for reexamination” not only because it created a Circuit

split but because of the “importance of the issue to the mutual fund industry.”

►

Subsequent to the Seventh Circuit’s ruling in Jones, and prior to the oral arguments

before the Supreme Court in that case, the Eighth Circuit held in Gallus v. Ameriprise

Financial Inc. that it was error for a district court to reject a comparison of the fees

charged by an investment adviser to its institutional and retail clients.

7

The Supreme Court Weighs In

►

Oral arguments, heard by the Supreme Court in early November 2009, focused on the nature

of the fiduciary duty under Section 36(b); the appropriate standard for measuring advisory fees

and the appropriateness of institutional versus retail advisory fee comparisons in Section 36(b)

inquiries; and the roles of fund boards and courts in Section 36(b) cases.

►

In its Jones opinion, which vacates the Seventh Circuit’s decision, the Supreme Court

embraced the Gartenberg standard as the correct approach in the review of challenged

advisory fees.

►

The Gartenberg framework, Justice Alito wrote for the unanimous Court, accurately

reflects the “delicate compromise” between shareholder and adviser interests that

Congress “embedded in §36(b).”

►

The Court recognized that “while the standard for an investment adviser’s fiduciary duty

has remained an open question in our Court…until the Seventh Circuit’s decision below,

something of a consensus had developed regarding the standard set forth 25 years ago

in Gartenberg.”

►

The Court’s opinion also noted that Gartenberg “has been adopted by other federal

courts, and ‘the SEC’s regulations have recognized, and formalized, Gartenberg-like

factors.’”

8

On Independent Directors

►

The Court’s opinion appears to be a major affirmation of the crucial role of informed and diligent

fund directors in overseeing fees and monitoring conflicts of interest.

►

►

Citing Burks v. Lasker, a case decided by the Court in 1979, the Court observed that

“[u]nder the Act, scrutiny of investment adviser compensation by a fully informed mutual

fund board is the ‘cornerstone of the…effort to control conflicts of interest within mutual

funds’…The Act interposes disinterested directors as ‘independent watchdogs’ of the

relationship between a mutual fund and its adviser.”

The Court also acknowledged that the Act “instructs courts to give board approval of an

adviser’s compensation ‘such consideration…as is deemed appropriate under all the

circumstances.’” The Court noted that from “this formulation, two inferences may be drawn.

►

First, a measure of deference to a board’s judgment may be appropriate in some

instances. Second, the appropriate measure of deference varies depending on the

circumstances.”

9

On Independent Directors (cont.)

►

According to the Court, “Gartenberg heeds these precepts. Gartenberg advises that ‘the

expertise of the independent trustees of a fund, whether they are fully informed about all facts

bearing on the [investment adviser’s] service and fee, and the extent of care and

conscientiousness with which they perform their duties are important factors to be considered in

deciding whether they and the [investment adviser] are guilty of a breach of fiduciary duty…’”

10

On Judicial Review of Board Decisions

►

The Jones opinion focused on the dangers associated with judicial review of a board’s decision

regarding advisory fees.

►

The Court stressed that “where a board’s process for negotiating and reviewing investmentadviser compensation is robust, a reviewing court should afford commensurate deference to the

outcome of the bargaining process.

►

Thus, if the disinterested directors considered the relevant factors, their decision to

approve a particular fee agreement is entitled to considerable weight, even if a court might

weigh the factors differently.”

11

On Judicial Review of Board Decisions (cont.)

►

The Court also considered the possibility that “a fee may be excessive even if it was negotiated

by a board in possession of all relevant information.”

►

In those instances, according to the Court, “a determination [by a court] must be based on

evidence that the fee ‘is so disproportionately large that it bears no reasonable relationship

to the services rendered and could not have been the product of arm’s-length bargaining.’”

►

Addressing a scenario in which “the board’s process was deficient or the adviser withheld

important information,” the Court stated that judicial review of the board’s decision must be

more “rigorous.” In any case, the Court stressed that “Section 36(b) does not call for

judicial second-guessing of informed board decisions.”

12

On Comparative Fees

►

The Court extensively reviewed the role of comparative fees in the Section 36(b) calculus.

►

Commenting on the usefulness of comparing a mutual fund’s advisory fees to the fees

charged by the fund’s adviser to other clients, the Court reasoned that “[s]ince the Act

requires consideration of all relevant factors…we do not think that there can be any

categorical rule regarding the comparisons of the fees charged different types of clients.

►

Instead, courts may give such comparisons the weight that they merit in light of the

similarities and differences between the services that the clients in question require.”

Warning against “inapt comparisons,” the Court noted that:

there may be significant differences between the services provided

by an investment adviser to a mutual fund and those it provides to a pension

fund which are attributable to the greater frequency of shareholder redemptions

in a mutual fund, the higher turnover of mutual fund assets, the more burdensome regulatory and

legal obligations, and the higher marketing costs. If the services rendered are sufficiently different

that a comparison is not probative, then courts must reject such a comparison. Even if the services

provided and the fees charged to an independent fund are relevant, courts should be mindful that

the Act does not necessarily ensure fee parity between mutual funds and institutional clients.

13

On Comparative Fees (cont.)

►

The Court also warned, as did the Gartenberg court, against placing too much emphasis on a

comparison of one fund’s advisory fees against fees charged to other mutual funds by other

advisers.

►

►

“These comparisons are problematic because these fees, like those challenged, may

not be the product of negotiations conducted at arm’s length.”

Moreover, the Court cited Gartenberg for the proposition that “competition between…funds for

shareholder business does not support an inference that competition must therefore also exist

between [investment advisers] for fund business. The former may be vigorous even though

the latter is virtually non-existent.”

14

On Advisers’ Fiduciary Duty

►

A significant portion of the Court’s opinion is dedicated to an exploration of the history of

Section 36(b), which was adopted by Congress in 1970, with the goal of illuminating the

meaning of the statutory statement that an investment adviser “shall be deemed to have a

fiduciary duty with respect to the receipt of compensation for services.”

►

Observing that the meaning of Section 36(b) “is hardly pellucid,” the Court affirmed that

the Gartenberg formulation “was correct.”

►

Citing its 1939 decision in Pepper v. Litton, the Court stated that “the essence of the test

[as to whether a fiduciary duty has been violated] is whether or not under all the

circumstances the transaction carries the earmarks of an arm’s length bargain.”

►

According to the Court, “[t]he Gartenberg approach fully incorporates this understanding of

the fiduciary duty…Gartenberg insists that all relevant circumstances be taken into account…”

►

The Court also highlighted that “[t]he Investment Company Act shifts the burden of proof from

the fiduciary to the party claiming breach,” thus emphasizing that plaintiffs (and not

investment advisers) continue to have the burden of proof when bringing suit under Section

36(b), as acknowledged in Gartenberg.

15

The Court’s Concluding Thoughts

►

The Court concluded its opinion by once more endorsing the principles articulated in

Gartenberg.

►

Noting that the “Gartenberg standard, which the [Seventh Circuit] panel rejected, may lack

sharp analytical clarity,” the Court emphasized that “we believe that it accurately reflects the

compromise that is embodied in Section 36(b), and it has provided a workable standard for

nearly three decades.

►

The debate between the Seventh Circuit panel and the dissent [in that Circuit]…

regarding today’s mutual fund market is a matter for Congress, not the courts.”

16

Roman L. Weil

Professor Emeritus of Accounting, Chicago Booth School of Business

Independent Director, MainStay Funds

roman@uchicago.edu

17

Gartenberg Factor #2: Profitability of the Fund to the Advisor

►

Martin and Chambers of WilmerHale say:

“The Court quotes the Gartenberg factors with approval. The Court did not, however, suggest

a priority consideration of the factors…Academic literature suggests that some of these

factors may not be relevant to assessing whether an advisory fee is excessive for fund

investors.”

“Commentators, for example, have written that the profitability of the fund to an investment

adviser measures the adviser's efficiencies in providing an advisory service and not whether

investors could obtain the same performance and services for a lower price at a competitor.”

“The Court neither acknowledges this debate, nor suggests how the lower courts should

assess fund profitability in investment advisory challenges. There are few judicial

pronouncements about fund profitability, which in turn provide scant guidance to boards

seeking to adhere to the Gartenberg formulation in reviewing investment advisory

agreements.”

18

What SCOTUS Says About Comparisons with Institutional Fees

►

“[C]ourts may give such comparisons the weight that they merit in light of the similarities

and differences between the services that the clients in question require, but courts must be

wary of inapt comparisons. As the panel below noted, there may be significant differences

between the services provided by an investment adviser to a mutual fund and those it

provides to a pension fund which are attributable to the greater frequency of shareholder

redemptions in a mutual fund, the higher turnover of mutual fund assets, the more

burdensome regulatory and legal obligations and higher marketing costs.”

19

Focus is Illusory

►

About profitability, plaintiff advocates [JP Freeman, SL Brown, and S Pomerantz] have said:

“…profitability calculations involve cost allocation issues that are subject to dispute, and there

is no universally accepted methodology for making that analysis…”

1. The authors say methodology, but they mean, merely, methods. Methodology is the

study of methods, not methods themselves. Compare, for example, sexology which is

the study of sex not, alas, sex itself.

2. More important: Not: ‘there is no….’ but “there can be no universally accepted

method…”

►

About profitability, counsel says:

“Don’t worry about profitability; the test is reasonableness, and the business judgment rule.”

►

Your economist asks:

“Where are the objective standards of reasonableness if not from financial analysis?”

►

Counsel doesn’t provide any.

20

The PROBLEM (on line 12)

Measuring Profitability of the Lines of Business and of the Individual Funds

Advisor Has

Mutual Funds

Pension

Funds

Total

Fund A

Allocation Bases

Dollars Managed

800,000

420,000

190,000

Number of Accounts

4

150

100

Average Account Size

200,000

1,900

Interquartile Range of Account size

500,000

1,520

Number of stocks in Fund

350

170

100

Valuation Committee Time

1

107

2

Direct Employees

5

24

10

Direct Payroll

400,000

2,360,000

900,000

Outside auditor charges per fund

5,000

24,000

10,000

Fees for Services ………………………

800

900

400

Direct Costs are $340, $50 for Pension Funds and $290 for Mutual Funds.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12 Common Costs are $1,100.

Fund B

140,000

40

3,500

2,100

40

5

8

800,000

6,000

300

Fund C

90,000

10

9,000

1,800

30

100

6

660,000

8,000

200

Totals

1,220,000

154

520

108

29

2,760,000

29,000

1,700

21

Allocating Common Costs Using Number of Accounts

Measuring Profitability of the Lines of Business and of the Individual Funds

A dvisor Has

Mutual Funds

P ension

Fund s

1 Numbe r of Accou nts

2 Fees for Services … … ……… …… ……

Total

4

Fund A

150

800

Fund B

1 00

9 00

40

400

Total s

F und C

3 00

10

154

20 0

1 ,7 00

A dvisor Has

Mutual Funds

P ension

Fund s

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

Total

Fund A

Fund B

Total s

F und C

Fees for Services … … ……… …… ……

800

9 00

400

3 00

20 0

1 ,7 00

Direct Costs ……… …… ……… …… …

Contribu tio n Mar gin …… … ……… ……

50

750

2 90

6 10

120

280

1 10

1 90

60

14 0

3 40

1 ,3 60

29

1 ,0 71

All oca tion o f Indir ect Co sts

To Line s of Busin ess …… …… ……

1 ,1 00

1 ,1 00

To Individu al Fu nds …… …… ……

Pr ofi t Margin … …… ……… … ……… …

P ercentage of Fees … ……… … …

Assets

S pecifi ca lly Id entifi able

Comm on

Rate of R etur n on Assets

714

721

(4 61)

90.2%

2 86

(434 )

(96)

-108.6%

-31.9%

Numbe r of Accou nts

71

1 ,0 71

69

2 60

34.3%

200

5 00

333

1 33

33

7 00

66

2 ,4 84

1,656

6 62

16 6

2 ,5 50

3 ,2 50

271.0%

-1 5.5%

-21.8%

Direct Costs are $34 0, $50 for P ensio n Fu nds and $29 0 for Mu tu al Fund s.

Common Costs are $1,100.

B asis of

Alloca tio n

-12.0%

Numbe r of Accou nts

34.5 %

22

Allocating Common Costs Using Number of Stocks in the Account

Measuring Profitability of the Lines of Business and of the Individual Funds

Adviso r Has

Mutua l Funds

Pension

Fun ds

1

2

Nu mber of stocks in Fund

Fe es for Service s ………………………

Total

350

800

Fund A

170

900

Fun d B

100

400

40

3 00

Totals

Fund C

30

200

520

1 ,700

Adviso r Has

Mutua l Funds

Pension

Fun ds

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

Fe es for Service s ………………………

Di rect Costs ……………………………

Co ntribu tion Margin ……………………

Allocation o f Indi rect Costs

To Lines of Business ………………

To Individu al Funds ………………

Profit Margin ……………………………

P ercentage of Fees ………………

Assets

S pecifically Identifiable

Common

17

Common Costs are $1,100.

Total

Fund A

800

50

750

900

290

610

740

360

10

250

1.2%

200

1,716

500

834

400

120

280

Fun d B

3 00

1 10

1 90

Totals

Fund C

200

60

140

1 ,700

340

1 ,360

1,1 00

1,1 00

212

68

85

1 05

17.1%

35.1%

3 8.3 %

294

490

1 18

1 96

88

147

33.6%

32 .5%

Rate of Return on Assets

0.5%

18.8%

8.7%

Di rect Costs are $340, $50 for Pension Funds a nd $290 for Mu tual Funds.

63

77

Basis of

Allocation

Numbe r of Stocks in Fu nd

360

260

700

2 ,550 Numbe r of Stocks in Fu nd

3 ,250

23

Allocating Common Costs Using Ability to Bear

Measuring Profitability of the Lines of Business and of the Individual Funds

Adviso r Has

Mutua l Funds

Ability to Bear

Pension

Fun ds

1 Fe es for Service s ………………………

Total

800

Fund A

900

Fun d B

400

3 00

Totals

Fund C

200

1 ,700

Adviso r Has

Mutua l Funds

Pension

Fun ds

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

Fe es for Service s ………………………

Di rect Costs ……………………………

Co ntribu tion Margin ……………………

Allocation o f Indi rect Costs

To Lines of Business ………………

To Individu al Funds ………………

Profit Margin ……………………………

P ercentage of Fees ………………

Assets

S pecifically Identifiable

Common

Total

Fund A

800

50

750

900

290

610

607

493

400

120

280

3 00

1 10

1 90

Totals

Fund C

200

60

140

226

54

1 54

36

113

27

143

117

19.1%

19 .1%

19.1%

19.1%

1 9.1 %

17.9%

13.0%

13.4%

12.1%

13 .4%

200

1,406

500

1,144

230

525

1 56

3 56

115

263

10.2%

10 .2%

Basis of

Allocation

1 ,700

340

1 ,360

1,1 00

1,1 00

Rate of Return on Assets

10.2%

10.2%

10.2%

Di rect Costs are $340, $50 for Pension Funds a nd $290 for Mu tual Funds.

Common Costs are $1,10 0.

Fun d B

493

260

=

Contributi on Margi n

Called "Ability to Bear"

Profits/Contribution Mar gin

700

2 ,550

3 ,250

Contributi on Margi n

Called "Ability to Bear"

24

Allocation Bases are Many, Arbitrary, and Selection Matters

►

In the original Gartenberg case, experts for the plaintiff found the advisor enjoyed profits of 38

percent, while those for the defense found the funds suffered a loss.

Factors

Allocation Bases

Dollars Managed

Number of Accounts

Average Account Size

Interquartile Range of Account size

Number of stocks in Fund

Valuation Committee Time

Direct Employees

Direct Payroll

Outside auditor charges per fund

25

Which Ratio to Use to Assess Profitability?

Three Companies; Three Ratios Exercise

Revenues …………………… R

$

Income Before Interest

and Taxes ………………… YBIT

Net Income …………………… Y

Average During Year

Total Assets ………………… A

Common Shareholders'

Equity ……………………… SE

Big

Company

Medium

Small

A

Se

Sa

28.95

4.30

2.92

$

13.64

0.82

0.52

$

9.72

7.89

1.83

29.77

5.12

0.74

I. Profit Margin Ratio = Y/R …………

10.1%

3.8%

1.5%

II. Rate of Return on

Assets = YBIT/A ……………………

5.6%

10.4%

8.5%

III. Rate of Return on

Shareholders' Equity = Y/SE ……

9.8%

10.2%

20.0%

Sears

►

It takes more data to do

ROA, but not hard data, and

►

It requires allocations of fixed

costs, but no more or less

arbitrary than the allocations

already required to compute

profit margins.

0.16

0.15

77.11

AT&T

ROA beats Profit Margin

even though:

Safeway

26

24 Omitted Words

“If you are going to endorse Gartenberg standard, please throw out the profitability test, as it

has no economic nor other theoretically sound basis. “

27

Directors Should Consider…

►

Asking management for sensitivity analyses of the profitability measures they show us.

►

Starting process of assessing profitability of institutional line of business v. mutual fund family.

►

Being prepared to start addressing the Freeman, Brown, Pomerantz analysis of the fees of

advisors who charge different [much higher] fees to their own funds than to Vanguard for subadvising the same sort of funds.

Table 3 of their article shows:

1

2

3

Assets Managed in Millions

$ 10 $ 100 $ 1,000 $ 10,000 $ 25,000

Captive Fund Mean in bps ……… 70

69

66

64

63

Vanguard Mean in bps …………… 29

27

22

15

14

See, also, William Baumol’s 1990 book.

28

Q&A

Please type in your question using the Q&A button at the top of the screen

29

For More Information

Please contact Paul Ellenbogen at paul.ellenbogen@morningstar.com

30

![Literature Option [doc] - Department of French and Italian](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006916848_1-f8194c2266edb737cddebfb8fa0250f1-300x300.png)