management of multiple pregnancy and breech delivery

MANAGEMENT OF MULTIPLE PREGNANCY

AND BREECH DELIVERY

G. Capogna and D. Celleno, Dpt of Anesthesiology, Fatebenefratelli General

Hospital, Roma, Italy.

1. MULTIPLE GESTATIONS

1.1. GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Twin gestations occur in 1 % of pregnancies. Both infants are vertex 31-47 % of the time, while the first infant is vertex and the second infant is breech 30-40 % of the time. Breech-vertex or breech-breech presentations occur 8-12 % of the time and transverse lies occur in approximately 5-7 % of twins gestation. This variety of presentations influences both obstetric and anesthetic management.

The implications for anesthesia presented by twin and multiple gestation pregnancies is, in part, determined by the planned mode of delivery. In fact, some obstetrician advocate elective cesarean section as a means of reducing the high perinatal mortality rate seen with vaginal delivery [1]. The risks associated with twin pregnancy are well described and perinatal mortality rate for twins born by vaginal delivery is 3 to 6 times that for singleton pregnancies [2,3]. The increased perinatal morbidity and mortality relates in maternal and fetal factors as reported in

Table I [1-5].

MAPAR 1997

Table I

Perinatal problems associated with multiple gestation.

MATERNAL, PHYSIOLOGIC anemia increased cardiac stress aspiration supine hypotension respiratory difficulty increased lumbar lordosis, back edema

MATERNAL, OBSTETRIC pre-eclampsia gestational hypertension uterine atony abruption placenta previa polyhydramnios premature rupture of membranes preterm labor

FETAL prematurity (50 % of twins are between 32 and 38 weeks) intracranial hemorrhage (a result of compression and traction of the soft cranial vault during its descent through the pelvis) low birthweight high incidence of malpresentation congenital malformation prolapsed umbilical cord

The second twin carries the highest perinatal risk as a result of breech presentation and birth asphyxia. The latter may result from contraction or partial separation of the placenta after delivery of the first twin or a longer period during which the infant is subjected to the effects of aortocaval compression. On the basis of this, it has become a general principle to minimize the second stage of delivery of the second twin [1, 2, 6, 7]. Similarly, with triplets and quadruplets, the possibility of malpresentation in the later fetuses increases, increasing the requirement for version and breech extraction, both of which procedures are associated with a high incidence of morbidity-mortality [2].

90

Obstétrique

Obstetric management of twins include:

- prevention of preterm labor (bed rest, tocolysis),

- aggressive antepartum monitoring,

- ultrasound determinations of the presentation of the fetuses.

Twins presenting as vertex/vertex are usually delivered vaginally. If the first twin is breech, cesarean delivery is usually chosen. Management varies when the presenting twin is vertex and the second twin is non-vertex.

1.2. VAGINAL DELIVERY

Vaginal delivery of twins requires:

- the provision of good analgesia which facilitates a non-precipitate, atraumatic delivery,

- the capacity to provide conditions for rapid delivery by cesarean section, forceps delivery (with adequate perineal anesthesia and relaxation) or version and extraction (adequate perineal anesthesia and uterine relaxation),

- a minimal duration of second stage for the second twin,

- avoidance of factors which may contribute to fetal distress or depression.

Epidural analgesia for twin deliveries offers many advantages [8-11], including the following:

- elimination of the need for parenteral narcotics and sedatives (desirable in premature infants),

- analgesia may allow the mother to avoid unnecessary muscle activity and may diminish the cardiovascular work,

- prevention of the bearing-down reflex, allowing a controlled delivery,

- the ability to do an operative or instrumental delivery if needed.

Similar duration of labor and mode of delivery when epidural analgesia was compared to parenteral narcotics [9] and a better second twin's condition with epidural analgesia [11] has been reported. Experience with singleton pregnancies on the progress of labor support a reduction in motor block and instrumental delivery with concentrations of bupivacaine of 0.125 % or less. However, progressive sparing of involuntary expulsive reflexes may be less desirable in the delivery of twins, especially for premature and breech infants. In multiple pregnancy the incidence of instrumental delivery is also increased [12]. This may implies a reduced role for very low concentration solutions. However, a recent report demonstrated the value of ultra-low concentrations of bupivacaine associated with sufentanil which provided similar analgesia and did not affect neither the duration of labor nor the incidence of instrumental or surgical delivery when compared with the standard 0.125 % dose [13]. Continuous epidural analgesia would appear to achieve many of the goals outlined for twin deliveries. It provides satisfactory analgesia throughout first and second stages, and is readily modified to provide conditions for either cesarean section or instrumental vaginal delivery. However it does not provide uterine relaxation, which, traditionally, necessitates general anesthesia.

91

MAPAR 1997

More recently inhaled or parenteral glyceryl trinitrate has been used for this purpose [14]. Other techniques available include epidural and subarachnoid opioids, continuous or intermittent subarachnoid block, combined spinal-epidural analgesia, caudal and pudendal block.

Opioid analgesia provided acceptable analgesia only for the first stage of labor, but the considerations of prematurity and potential hypoxemia lend support to the caution of depressant drugs in these infants. Subarachnoid block may find occasional use if rapid anesthesia is desired, such as in precipitous delivery.

1.3. CESAREAN DELIVERY

The larger uterus encroaches to a greater degree upon the maternal functional residual capacity, increasing hypoxemia in the supine position. An unfavorable shift in the angle of the lower esophageal sphincter increases the possibility of regurgitation of gastric contents. General anesthesia has been associated with poorer outcome in the second twin [1, 2, 8]. All of these factors support the avoidance of general anesthesia.

Regional techniques include epidural and subarachnoid blocks.

Aortocaval compression is more pronounced in multiple pregnancies and incidence of hypotension may be greater with subarachnoid block. In addition, for equivalent doses and volumes of hyperbaric solution, subarachnoid block will develop more rapidly and will ascend an average of two spinal segments higher than in singleton pregnancies [15]. In multiple fetuses, because the tremendous enlarged uterus, spinal anesthesia can prove dangerously unpredictable. The unpredictability of response is a limitation of a single shot subarachnoid technique and for this reason, it may be preferable to consider the use of titrable techniques, such as epidural and combined epidural-spinal anesthesia.

Lumbar epidural anesthesia offers a slower onset of action, which may allow a better hemodynamic stability, a better flexibility and control of upper sensory blockade. Identifying the epidural- subarachnoid space may be more difficult in these women, because of the increased lumbar lordosis and the difficulty to assume a good position due to their greater enlarged uterus. Edema may further complicate identification of anatomical landmarks.

Uterine hypotonia and blood loss are increased in multiple pregnancies which may necessitate aggressive fluid replacement and oxytocic therapy.

Irrespective of the route of delivery, the second baby delivered is at higher risk for death and depression than is the first one. Depression is related to birth order and not presentation. The second infant, whether born abdominally or vaginally, has significantly lower 1-minute Apgar scores, and lower umbilical venous pH and pO

2

, and umbilical artery pO

2

[16]. The contribution of anesthesia to this poorer outcome is controversial, however a better second twin condition, assessed by acid-base status, has been reported with epidural analgesia [11]. An appropriate choice of the anesthetic technique and a perfect performance, including the avoidance of maternal

92

Obstétrique and fetal depression and of aortocaval compression, certainly may contribute to an happy outcome.

2. BREECH PRESENTATION

2.1. GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Breech presentation is defined as the entrance of the fetal lower extremities of pelvis into the maternal pelvic inlet. Three types are described:

- frank breech, where the hips are flexed and the knees extended

- complete breech, where the hips and knees are both flexed

- footling breech, where one or both hips are not flexed and one or both feet are below the buttocks.

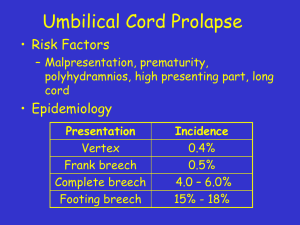

These different types of presentation depend on gestational age and fetal size, since before 28 weeks' gestation, 25 % of fetuses are breech. Breech presentation complicates 3-4 % of pregnancies [17] and in Table II is reported the incidence of the different breech presentations in relationship to the weight of the fetus, in singleton term pregnancy.

Table II

Infant’s weight frank breech complete breech footling breech

< 2500 g

38 %

12 %

50 %

> 2500 g

51-73 %

4-11 %

20-24 %

Table III

Perinatal problems associated with breech presentation.

MATERNAL postpartum infection uterine atony and postpartum hemorrhage cervical trauma and manipulation use of uterine relaxants

FETAL prematurity congenital anomalies birth asphyxia birth trauma

6 % umbilical cord prolapse (4-7 %) intracranial hemorrhage or other neonatal traumas

93

MAPAR 1997

In Table III are reported the most common problems related to breech delivery.

Because of the risks of birth anoxia and trauma, few breech infants are delivered vaginally. In the recent years, 75 % cesarean section rate has been reported [18].

Term frank breech infants weighting between 2500 and 3800 g, with the fetal head in the flexed position may deliver vaginally with little increased risk [17]. The remainder of breech fetuses are delivered by cesarean section. In many institutions all viable breech fetuses are delivered by cesarean section.

2.2. VAGINAL DELIVERY

The risks associated with vaginal delivery include [2, 4, 19-21]:

- a higher incidence of dysfunctional labor, with a prolonged first as well as second stage,

- arrest of the after-coming head either due to dystocia or containment by an incompletely dilated cervix, especially in case of premature pushing or small infants in premature labor with consequent fetal asphyxia due to umbilical cord compression,

- increased risk of cord prolapse,

- forceps delivery is associated with an increased intracranial hemorrhage, and this may represent a particular problem with premature breech infants,

- possible injuries to the spinal cord, peripheral nerves or intra-abdominal organs.

The choice of method of delivery (cesarean section vs trial of vaginal delivery) is dependent on fetal gestational age, on the type of breech presentation (term frank or complete breech), and on local obstetrical consensus [22].

The anesthetic management in breech vaginal delivery include:

- an adequate perineal analgesia to facilitate regular examinations and to prevent a premature bearing-down reflex before full cervical dilatation,

- a slow, controlled delivery over a relaxed perineum,

- the ability to rapidly create the conditions for an instrumental delivery,

- the ability to relax the uterus, if needed,

- a special attention in case of premature or distressed fetus.

The sparing effect on perineal muscle tone which has been achieved in cephalic presentations with very low concentrations of bupivacaine and opioids

(e.g. 0.0625 %) may be associated with a less reliable suppression of the bearingdown reflex. A titration of the dose to obtain an adequate perineal relaxation, analgesia and reduction of the bearing down-reflex may be easily achieved increasing local anesthetic concentration, with or without opioids [23-25]. For these reasons very dilute solutions of local anesthetics and opioids may be used in the first stage followed by more concentrated solutions later on, in order to obtund the involuntary urge to push.

Spinal analgesia may also provide an excellent perineal relaxation for breech delivery, and may be used when these conditions are required rapidly and epidural analgesia has not been established. The extent of sensory and motor block can be controlled by exploiting concentration and baricity.

94

Obstétrique

The requirements for an emergency intervention is higher in breech delivery.

Acute cord prolapse and fetal distress, as well as assisted delivery of the aftercoming head following spontaneous delivery of the breech and total breech extraction are not uncommon situations. If time permits, all these situations may be managed using a regional technique. If uterine relaxation is needed and general anesthesia is not possible or undesirable, small boluses of glyceryl trinitrate have been suggested as the technique compatible with regional anesthesia without a prolonged uterine atony because its short half-life [14]. Local anesthetics are not tocolytic and extending the block does not create any advantage.

2.3. CESAREAN DELIVERY

Emergency cesarean delivery for cord prolapse or fetal distress requires general anesthesia unless an epidural catheter is already in place. If time permits, spinal anesthesia may be also used for the "urgent" cesarean delivery.

For elective cesarean delivery, regional anesthesia is the technique of choice.

Particularly for breech infants, epidural anesthesia warrants better neonatal conditions at birth when compared with general anesthesia [26].

The premature breech fetus, in case of asphyxia, is more sensitive to maternal depressant agents, making regional anesthesia even more desirable in this case.

It should be remembered that the patient in preterm labor may have received tocolytic therapy that may predispose her to pulmonary edema with aggressive hydration.

95

MAPAR 1997

REFERENCES BIBLIOGRAPHIQUES

[1] Guttmacher Af, Schuyler GK. The fetus of multiple gestation. Obstet Gynecol

1958;12:528-541

[2] James FM. Anesthetic considerations for breech or twin delivery. Clin Perinatol

1982;9:77-94

[3] Malinov AM, Ostheimer GW. Anesthesia for the high risk parturient. Obstet Gynecol

1987;69:951-964

[4] O'Driscoll K, Meagher D. Traumatic intracranial haemorrhage in first born infants and delivery with obstetric forceps. Br J Obst Gynecol 1987;88:577-579

[5] Chiswick ML, James DK. Kiellands forceps: association with neonatal morbidity and mortality. Br Med J 1979;7-9

[6] Craft JB, Levinson G, Shnider SM. Anaesthetic considerations in cesarean section for quadruplets. Can Anaesth Soc J 1978;25:236-239

[7] Little WA, Friedman EA. The twin delivery: factors influencing second twin mortality.

A review. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1958;13:611

[8] Aaron JB, Halpern J. Fetal survival in 376 twin deliveries. Am J Obstet Gynecol

1955;69:794

[9] Weeks ARL, Cheridjian VE, Mwanje DK. Lumbar epidural analgesia in labour in twin pregnancy. Br Med J 1977;2:730

[10] James FM III, Crawford JS, Davies P, Naiem H. Lumbar epidural analgesia for labor and delivery of twins. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1977;127:176

[11] Crawford JS. A prospective study of 200 consecutive twin deliveries. Anaesthesia

1987;42:33-39

[12] Zuidema L. Twin pregnancy. The management of labor. Clin Perinatal 1988;15:87-91

[13] Prayssac P, Mercier FJ, Benhamou D. Extradural analgesia for twin delivery: a randomized comparison of 0.125 % bupivacaine and 0.0635 % bupivacaine with sufentanil.

Br J Anaesth 1996;76(Suppl)A:332

[14] Mayer DC, Weeks S. Antepartum uterine relaxation with nitroglycerin in caesarean delivery. Can J Anesth 1992;39:166-169

[15] Jawan B, Lee JH, Chong ZK, Chang CS. Spread of spinal anaesthesia for caesarean scetion in singleton and twin pregnancies. Br J Anaesth 1993;70:639-641

[16] Young B, Sudan J, Antone C. Differences in twins: the importances of birth order.

Am J Obstet gynecol 1985;151:915

[17] Collea JV. Current management of breech presentation. Clin Obstet Gynecol

1980;23:525-530

[18] Cunningham FG, MacDonald CT, Gant NF. William's Obstetrics. 18th ed. Norwalk,

CT: Appleton and Lange 1989:349

[19] Lyons ER, Papsin FR. Cesarean section in the management of breech delivery.

Am J Obstet Gynecol 1978; 130:558-561

[20] Decrespigny LJC, Pepperrell RJ. Perinatal morbidity and mortality in breech presentation. Obstet Gynecol 1979; 53:141-145

[21] Donnai ADG. Epidural analgesia, fetal monitoring and the conditions of the baby at birth with breech presentation. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1975;82:360-365

96

Obstétrique

[22] Society of Gynecologists of Canada. The Canadian Consensus on Breech Management at Term. Journal of SOGC 1994;16:1839-1848

[23] Confino E, Ismajovich B, Rudick V, David MP. Extradural analgesia in the management of singleton breech delivery. Br J anaesth 1985;57:892-895

[24] Breeson AJ, Kovacs GT, Pickles BG, Hill JG. Extradural analgesia. the preferred method of analgesia for vaginal breech delivery. Br J Anaesth 1978;50:1227-1230

[25] Bowen-Simpkins P, Fergusson IL. Lumbar epidural block for the breech presentation.

Br J Anaesth 1974;46:420-424

[26] Crawford SJ, Davies P. Status of neonates delivered by elective cesrean section.

Br J Anaesth 1982; 54:1015-1020

[27] Barrier G, Sureau C. effects of anesthetic and analgesic drugs on labour, fetus and neonate. Clin Obstet Gynaecol 1982;9:351

97