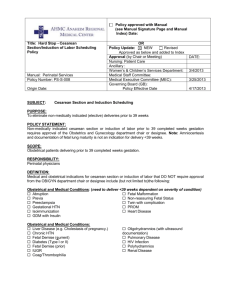

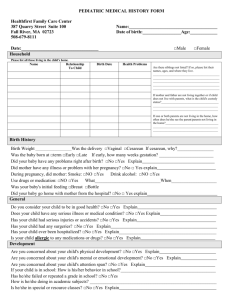

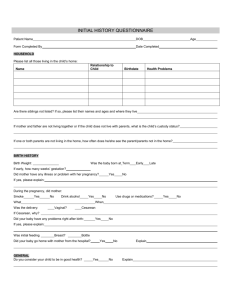

Clinical Guidelines for Obstetrical Services

advertisement