Paper 17

advertisement

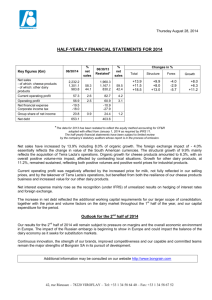

DEPARTMENT OF FOOD ECONOMICS Discussion Paper Series Economies of Scale and Dairy Product Manufacturing Enterprises by Dr. Michael Keane Agribusiness Discussion Paper No. 17 January 1998 Department of Food Economics University College, Cork Ireland Economies of Scale and Irish Cheese Manufacture Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................... Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ Economies of Scale and Dairy Processing - Introduction .......................................... Economies of Scale - Theoretical Aspects................................................................. Research on Economies of Scale and Irish Dairy Processing .................................... Economies of Scale - Empirical Studies ................................................................... The EU Cheese Industry ................................................................................................. The Irish Cheese Industry ............................................................................................... Milk Collection Costs and Cheese Manufacturing Costs - Ireland................................. Discussion and Conclusions ........................................................................................... References....................................................................................................................... 1 Economies of Scale and Irish Cheese Manufacture Economies of Scale and Dairy Product Manufacturing Enterprises Dr. Michael Keane Abstract This paper discusses the issue of economies of scale with particular reference to Irish cheese manufacture. The economic engineering approach is used to determine optimum size of cheese manufacturing plants while taking into account milk collection costs. It was noted that results using this approach provide for an optimum size which differs greatly from industry structure in practice. It was speculated that broader industry and market considerations, involving in particular the prospect of smaller firms obtaining premia through product variety, may explain the difference. 2 Economies of Scale and Irish Cheese Manufacture Executive Summary This paper discusses the issue of economies of scale in relation to Irish and E.U. cheese manufacture. Theoretical aspects of economies of scale are discussed and linked to dairy industry economics. It is suggested that the study of economies of scale in dairy processing plants should be combined with the effect of scale on milk collection costs in order to determine optimum scale. The evolution of the E.U. and Irish cheese industry is discussed as well as past economies of scale studies involving the Irish dairy industry. Detailed information on milk collection costs was obtained to determine the relationship between collection costs and distance from processing plant. Using the economic engineering approach detailed information on cheese manufacturing costs was also obtained with emphasis on the relationship between size of plant and unit manufacturing costs. The information on milk collection and cheese manufacturing cost was combined to determine the optimum plant size. It was concluded using this approach that there were considerable economies of scale in cheese manufacture, a result which was quite similar to that obtained in a similar study in Germany. However it was noted that this result was widely at variance with E.U. cheese industry structure in practice. It was concluded that rigid adherence to the economic engineering approach may be inappropriate in an industry such as the cheese industry in determining economies of scale. Broader industry and market considerations, involving in particular the prospect of small enterprises obtaining premia in the market through product differentiation and also X-efficiency, may be important factors in explaining the difference between economic theory and industry practice. Economies of Scale and Dairy Processing 3 Economies of Scale and Irish Cheese Manufacture Introduction The determination of the optimum size of enterprise is a complex issue involving many considerations. These include the extent of economies of scale in the activity in which the enterprise is involved and a range of competitive aspects related to the business environment in which the enterprise operates. As summarised by Porter (1979) the latter include: - Jockeying for position among current competitors in the industry - The bargaining power of customers - The bargaining power of suppliers - The threat of new entrants - The threat of substitute products or services This paper concentrates on one aspect of the determination of optimum size, the extent of economies of scale at manufacturing plant level in dairy processing. Economies of Scale – Theoretical Aspects The existence of economies of scale depends on the characteristics of the production function pertaining to different industries. This can be written as y = Y(K,L) in which y = the level of output per unit time, K = the amount of capital per unit time, L = the amount of labour per unit time. There are increasing economies of scale when increasing K and L each by the constant proportion a will result in a more than proportional increase in y: k a y = f(a K, aL). 4 Economies of Scale and Irish Cheese Manufacture with K > 1. Many reasons may be cited for lower long term average costs at a greater output, Hay and Morris, (1991); (a) the division of labour (b) indivisible equipment and the principle of multiples (c) three dimensional equipment and the relationship between surface area and capacity (d) the economies of massed reserves (e) dynamic economies through learning processes (f) technological development and scale Additional economies of scale at the level of the firm involve such factors as research and development, management, advertising, computer services, and centralised accounting, Hay and Morris (1991). Further economies of scale, realised when costs are reduced by producing two or more products jointly, rather than in separate specialised plants, are also relevant, particularly in a multiproduct industry such as the dairy industry. Scherer (1990). Also, large diversified firms “can make their purchasing power felt in dealing with specialised suppliers (and) financial groups may be better able to overcome the imperfections of the capital market”, de Jong (1988). Diseconomies of scale may also exist beyond a certain size, connected with such factors as increasing problems of information and co-ordination, and problems of budgetary control. To quote de Jong (1988), “such firms risk becoming overly bureaucratic so that technological scale advantages are outweighed by administrative and organisation inefficiencies. Internal inefficiency may hamper company performance”. Broader competitive forces involving, for example, the market power of buyers and suppliers, are also relevant. Economists express economies of scale in terms of unit cost curves. Studies of cost curves in many industries have found a downward sloping short-term cost curve, as fixed costs can be spread over a larger number of units as output increases; however if output expansion approaches capacity limits, the cost curve will bend sharply upwards. The long term average cost curve is generally found to be more L shaped then U shaped, indicating that beyond 5 Economies of Scale and Irish Cheese Manufacture a zone of decreasing unit costs, average and marginal long-term unit costs remain constant, de Jong (1988). In a discussion of cost curves in the long run, Hay and Morris (1991) point out many of the difficulties in empirical work, including different depreciation conventions, the difficulty of distinguishing monopoly profit and differences in cost assignment and rent imputation. The issue of economies of scale in dairy processing is regularly discussed internationally, with Krell and Wietbrauk (1993), Caraveli and Traill (1997), Pitts (1998) as recent examples. In the case of dairy processing, involving a perishable raw material which is almost 90% water, produced in widely dispersed small-scale family farms, it is the author’s view that the issue of economies of scale at manufacturing level must be combined with that of milk collection costs. While product distribution costs may also need to be taken into account in some cases, these costs may generally be ignored for many processes, as much of dairy product manufacture involves very great weight reduction, so that distribution costs are minimal relative to milk collection. Optimum dairy industry structure at manufacturing plant level then normally involves a balancing of decreasing average processing plant costs with increasing scale against increasing collection costs. The economic impact of distance on collection costs has been elaborated on in many texts, Hay and Morris (1991). Discussed in a specific dairying context by Bressler and King (1970), it was shown that if the density of production is held constant, the volume delivered to a plant from a circular area will be a direct function of the area and hence of the square of the radius. Collection costs will tend to increase with distance at a constant rate, but because of the quadratic relation between distance and volume, the marginal costs of collection will increase with volume at a decreasing rate. Total collection costs will therefore be related to the cube of the radius. Shown in conventional average and marginal costs terms (Fig.1), plant costs per unit are at their lowest at point a, whereas combined plant and collection costs are minimised at a lower volume at point b. Figure 1 Collection and Plant Costs Expressed in terms of Average Costs per Unit of Produce Handled 6 Economies of Scale and Irish Cheese Manufacture ACc MCc ACp MCp ACa MCa = = = = = = Average Costs (processing and assembly combined) Marginal Costs (processing and assembly combined) Average Costs (processing) Marginal Costs (processing) Average Costs (assembly) Marginal Costs (assembly) Source: Bressler and King (1970) Research on, Economies of Scale and Irish Dairy Processing The three main methods of economic analysis of industry structure are empirical cost analysis, budgetary or engineering analysis and the survivor technique, Hay and Morris (1991). While empirical cost analysis has the advantage of being based on actual industry data, it is often difficult to obtain such data due to confidentiality. Studies using the economic engineering and survivor techniques have been employed on an occasional basis in past decades in analyses of the Irish Dairy industry, Lynch (1967), O’Dwyer (1968), O’Dwyer (1970). economies of scale in the manufacture of creamery butter in Ireland in the late 1960’s. Completing budgets for five plant sizes, he demonstrated the existence of economies of scale with unit costs being more than halved in moving from the smallest to the largest plant. Based on the methodology of Stollstemier (1963) which again involves the engineering technique, O’Dwyer (1968) determined the optimum number, location and size of butter and skim powder plants in Munster and Co. Kilkenny. The information required 7 Economies of Scale and Irish Cheese Manufacture included (a) quantity or raw material (milk) at each origin, (b) a transportation cost matrix for each source-destination pair, and (c) a plant cost function. He concluded that 23 plants would minimise the total assembly and processing costs in the area, compared with the 135 plants in operation in the region at the time, O’Dwyer (1968). There has also been a very large number of reports in which structural change and economies of scale have been discussed in relation to Irish dairy processing, Cook and Sprague (1968), Keane and Pitts (1981), Boston Consulting Group (1983), ICOS (1985), ICOS (1987), Keane (1989), Gill and Butler (1989), Pitts (1989), Pitts (1990), DAFF (1990), Hayes (1991), PA (1992), Pitts (1992), Goe (1993), DAFF (1993), Zwanenberg (1996), Tozanli (1997). However, no study using the economic engineering/survivor technique approaches has been completed in recent years. One fairly recent study using the benchmarking approach has compared dairy product manufacturing costs for a number of countries for butter, cheese, whole milk powder and skim milk powder based on personal interviews, company and public cost data, Boston Consulting Group (1993). A summary of the results shows that, when taking “lowest cost in country”, costs are generally lowest for New Zealand, with Irish costs for butter manufacture an estimated 25% higher than New Zealand and Irish cheese manufacturing costs 68% higher (Table 1). In the absence of detailed knowledge of sources, comment on the quality of this information is not possible. Table 1 Dairy Product Manufacturing (Conversion) Costs, Comparisons, Index Based on “Lowest Cost In Country” New Zealand Ireland Netherlands Butter Cheese Whole Milk Powder Skim Milk Powder 100 125 117 100 168 123 100 100 102 114 8 Economies of Scale and Irish Cheese Manufacture Australia 116 181 94 USA 114 90 Source: Derived from Boston Consulting Group (1993) 106 101 Economies of Scale – Empirical Studies Two key practical aspects of empirical studies of economies of scale are (a) whether the study should be at manufacturing plant or overall enterprise level, (b) in relation to dairy processing, whether it should be multi-product or single product. Manufacturing Plant or Overall Enterprise Level Confusion sometimes arises in economies of scale studies regarding the level at which the study is being conducted i.e. at manufacturing plant or overall enterprise levels. (A business enterprise may of course involve many manufacturing plants). For example, the economic engineering approach is particularly suited to studies of scale at manufacturing plant level, whereas the survivor technique is normally applied at the overall enterprise level. In this paper analysis is primarily at the level of manufacturing plant. Choice of Dairy Product Many dairy firms are multi-product, as they benefit at both manufacturing, management and marketing levels from shared services. The study of economies of scale at a multi-product level is however quite complex, hence this study is confined to the single product level. The main manufactured dairy products are butter and skim milk powder as joint products, and cheese. Cheese was chosen as the product for study of economies of scale as (a) average output per plant has always been high for milk powder manufacture due to the nature of the technology involved, (b) the reduction in the number of enterprises manufacturing cheese over time has been much lower than 9 Economies of Scale and Irish Cheese Manufacture that for butter, CEC (1996), making it more interesting and relevant from a research viewpoint. The EU Cheese Industry Based on the triennial studies completed by the European Commission, CEC (1996), the number of cheese enterprises fell from 2,461 to 1,132 between 1976 and 1994 for the six major Northern European countries for which consistent data is available over a long period of time, representing a fall of 54% (Table 2). The reduction in the number of cheese enterprises was considerable in all countries with the exception of Ireland (Table 2). Average cheese output per enterprise increased very substantially for all countries. However in 1994 there was huge variation between countries in average output per enterprise, ranging from about 44,000 tonnes per enterprise in the Netherlands to less than 1,000 tonnes per enterprise in Belgium (Table 3). Table 2 Changes in Industry Structure, Cheese 1976 1985 1994 No. Enterprises Belgium 110 85 79 Denmark 202 70 39 Germany 537 361 248 France 1,551 1,189 739 Ireland 12 13 12 10 Economies of Scale and Irish Cheese Manufacture Netherlands 49 26 15 2,461 1,744 1,132 100 71 46 1976 1985 1994 Belgium 373 576 885 Denmark 777 3,650 7,350 Germany 1,210 2,529 5,642 France 612 1,070 2,105 Ireland 4,083 6,046 7,722 Netherlands 7,735 20,192 43,980 Total (6 countries) Index Source: Derived from CEC (1996) Table 3 Average Output per Enterprise, Tonnes Source: Derived from CEC (1996) More detailed analysis of cheese manufacture by dairy enterprise structure shows that 90% of enterprises in the six major countries in 1994 had an output of less than 10,000 tonnes p.a. while 82% had an output less than 4,000 tonnes (Figure 2). 11 Economies of Scale and Irish Cheese Manufacture Figure 2 Manufacturing Enterprises by Size in EU (6), 1994 600 500 400 300 200 100 0 <0.1 0.1-1.0 1.0-5.0 5.0-10.0 >10.0 1,000 tonnes p.a. Derived from [4] The Irish Cheese Industry The development of the Irish cheese industry in the twentieth century has been outlined by authors such as McCarthy (1992) and Foley (1993). The period 1910-21 is generally regarded as the first era of commercial production, with the number of factories rising to about 200 in 1919 with exports of over 14,000 tonnes to Britain, McCarthy (1992). This industry declined greatly in the 1920’s, as creameries reverted to butter production following the end of World War I, associated with a major price decline for cheese arising from the decontrolling of price by the British Food Controller in 1919. There were some developments in cheese-making from the 1930’s to the 1960’s pioneered by Mitchelstown Co-op and the Golden Vale Federation, such that by 1966, 21 factories were producing a total of about 17,000 tonnes p.a. (Table 4). 12 Economies of Scale and Irish Cheese Manufacture There was a substantial decline in the number of factory cheese enterprises in Ireland between the mid 1960’s and mid 1970’s, though much less dramatic than for butter. Despite recommendations for major further rationalisation in cheddar manufacture, such as the report of the Boston Consulting Group (1983), structural change since then has been quite limited. With overall factory cheese output increasing over five-fold between 1966 and 1996, there was more than a ten-fold increase in output per enterprise (Table 4). Table 4: Cheese Output and Enterprises - Ireland Year Output, ‘000 tonnes Cheese Enterprises 1966 1976 1986 1996 17 49 63 92 21 12 11 10 Source: Irish Dairy Board Milk Collection Costs and Cheese Manufacturing Costs – Ireland Milk collection and cheese manufacturing costs are first considered separately and then combined to provide overall estimates of economies of scale at manufacturing level. Cheese Manufacturing Costs A profile of cheese manufacturing costs related to scale was established through personal interview with cheese manufacturers and associated institutions. Following the discussions, detailed information was available on cheese manufacturing costs, including itemised costs for the various fixed 13 Economies of Scale and Irish Cheese Manufacture and variable cost components. From this information, incremental and average cost curves for cheese manufacture were derived. Both curves were decreasing at a decreasing rate, as might have been expected, indicating considerable economies of scale up to about 20,000 tonnes p.a. with limited further reductions beyond this size. (Figure 3). Figure 3 Cheese Manufacture: Estimated Costs 25 Pence Per Gallon 20 15 10 A verage C ost 5 M arginal C ost 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 T housand T onnes Milk Collection Costs Detailed information on milk collection costs was obtained from Irish dairy industry sources for tanker loads which were collected in regions which ranged from very close to the processing plant to up to one hundred miles distant. In all 60 observations were made. From the observations it was possible to estimate an incremental cost curve (Figures 4,5). Reviewing the scatter diagrams, it was clear that a simple linear function would be appropriate, despite the fact that the theoretical functional form for such a relationship is curvilinear as in Figure 1. It was not surprising to find that a linear function was appropriate, as despite the theoretical expectation, linear functions often fit well in such work when observations are limited to a given relevant range. Figure 4 Incremental Milk Transport Cost 14 Economies of Scale and Irish Cheese Manufacture Figure 5 Average Milk Transport Cost 15 Economies of Scale and Irish Cheese Manufacture Million Gals p.a. Combined Manufacturing and Collection Costs The previous estimates of cheese manufacturing and milk collection costs were then combined to establish the overall average and incremental cost curves. In the case of cheese manufacture this involved conversion from tonnages to volumes of milk equivalent. The estimates show that while the addition of milk collection costs has flattened the economies of scale curve slightly, estimated scale economies up to 20,000 tonnes p.a. remain considerable (Figure 6). The associated overall incremental cost curve continued to decline at a decreasing rate, although one could anticipate that it might begin to turn upwards a little beyond the range of milk volumes considered. Figure 6 Combined Costs, Cheese Manufacturing plus Milk Transport 30 25 Pence Per Gallon 20 15 10 5 A v e ra g e C o s t M a r g in a l C o s t 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 M illio n G a llo n s P .A . Comparison with Other Studies The above analysis would seem to indicate that there are considerable economies of scale in factory cheese production. The analysis may be 16 Economies of Scale and Irish Cheese Manufacture compared with similar studies in other countries. One research contribution in particular which seems relevant is based on the model of costs of operations in the dairy industry as completed on an ongoing basis by the Federal Dairy Research Institute in Kiel, Germany. Some recent results from this research have been discussed by Pitts (1998). One set of results shows the budgeted costs of manufacturing Gouda cheese where volumes produced range from 1,000 to 30,000 tonnes p.a., with associated plant capacity utilisation ranging from 21% to 100%. Results for a mid-range set of estimates, based on 2 shifts and 65% capacity utilisation, show considerable economies of scale (Figure 7). These results can readily be compared with the Irish results earlier, as both have estimated costs for a 20,000 tonnes p.a. output and this output level can be set at 100 for comparative purposes. The comparison showed that the pattern of estimated economies of scale is quite similar in both the Irish and German studies (Figure 7), with both studies clearly indicating that there are considerable economies of scale in cheese manufacture. Figure 7 Comparative Manufacture Economies of Scale Estimates for Cheese 160 150 140 Index 130 120 110 100 90 80 I 70 Germany 60 0 2 4 6 Discussion and Conclusions 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 Thousand Tonnes As shown above, studies at manufacturing plant level have indicated that there are considerable economies of scale up to about 20,000 tonnes cheese per annum in both Ireland and Germany (Figure 7). However, despite considerable change over the years, the actual structure of the cheese industry shows that 90% of all cheese enterprises in six major European dairy 17 Economies of Scale and Irish Cheese Manufacture countries had less than 10,000 tonnes output in 1994 (Fig 2). Obviously there is a total contradiction between these two observations. Based on the economies of scale studies one would expect the large enterprises to dominate the industry. This leads to discussion of comparative performance relative to scale of enterprise in practice. Reviews of actual performance in dairy manufacturing related to scale of enterprise requires agreement firstly on appropriate indicators of performance. While detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this paper (see O’Connell (1997)), one important indicator is the price paid to farmer suppliers of milk, given that much of the European Dairy industry is owned by milk producer co-operatives. These are at least two creditable annual producer milk price comparisons which have been ongoing within the EU for a number of years, Irish Farmers Journal (1998), Aarts (1997). Based on a very preliminary analysis of these milk price comparisons, there seems to be little evidence that large enterprises are paying consistently higher prices to producers than smaller enterprises. Hence smaller enterprises in general seem to be successfully using various means to obviate their inability to benefit from economies of scale. In reviewing means by which smaller enterprises may counteract economies of scale problems, at least two possibilities may be suggested, product differentiation and X-efficiency. Product Differentiation In discussing product differentiation one must at the outset acknowledge the characteristics of a product such as cheese. Cheese is a biological product in which consumers perceive a very wide range of subtle flavour differences. Thus there is a very wide variety of cheese products, with some countries having a very large number of small artisan-type enterprises, each producing its own unique variety. Even though Irish cheese production is mainly larger scale factory production for a mass consumer market (mainly factory cheddar), a parallel industry involving farmhouse cheese production has 18 Economies of Scale and Irish Cheese Manufacture expanded considerably in recent years, Kenneally (1996). Thus the nature of the product lends itself to great variety, with limitations to scale due to size of market in relation to many of these varieties. In this context one must acknowledge the limitations of the economic engineering approach to economies of scale at plant level in relation to determining the optimum size of enterprise. An enterprise operates in a business environment in which many opportunities and threats exist. In many cases, opportunities can be exploited by providing products for market segments where substantial premia can be obtained, even though production for these market segments may not be suited to large scale manufacture. In most industries, small firms providing products for “niche” markets survive in parallel with large firms meeting the needs of the mass market. There is no reason to believe that this should not also happen in dairying, and despite the changing structure of the EU cheese industry over the years as shown earlier, this feature is very much in evidence. X-Efficiency There are various studies by economists who suggest that large firms may sometimes not fully realise potential gains. In economic theory a common assumption of production analysis is that enterprises operate on the frontier of efficient techniques, at a technique determined by least cost. This assumption has been challenged, with the term x-effeciency being coined to express the potential gains in performance that enterprises could achieve without changing inputs as such. Reasons given for less than optimum performance include internal factors, involving labour contracts and motivation, and external factors related to competition, Hay and Morris (1991). With regard to external factors it is argued that “the lack of competition in the market leads to slack within the firm, or ….. the firms standard for its costs will probably not be the absolute level of costs it could attain, but rather to keep its costs in line with those of the industry as a whole”, Hay and Morris (1991) Irish Dairy Processing and the Future 19 Economies of Scale and Irish Cheese Manufacture In considering the optimum future structure for Irish Dairy Processing, it is clear that there is a need for a small number of very large enterprises which can compete at a global level. As stated by Rabobank (1998), “gradual trade liberalisation, investments in technology and the globalisation of food retail, food services and food industries are creating a need for strong, globally orientated food companies with a solid financial base”. The successful development of enterprises such as the Kerry Group, AWG, Dairygold, Golden Vale and the Irish Dairy Board represent a very positive Irish response to this need. At the smaller dairy enterprise level, the key to survival, given the presence of major economies of scale for standard products, would seem to be the development of specialised products for niche markets while ensuring that absolute efficiency is achieved at their given scale. Premia earned for specialised products may help to counteract the disadvantages of being unable to benefit from economies of scale. From a strategic viewpoint, the weakest position for dairy enterprises to be in is to be of small scale and to be producing standard mass-market products where major economies of scale are present and no premia are possible. Such enterprises will be vulnerable unless they pursue the development of differentiating features to provide premia to counteract their scale problem or achieve superior levels of efficiency at their given scale. From a methodological viewpoint, the overall conclusion is that while economic engineering type studies may reveal substantial economies of scale, broader industry considerations, involving such factors as the opportunity to obtain premia through product variety and consideration of x-efficiency, should be taken into account before any definitive conclusions on scale can be drawn. 20 Economies of Scale and Irish Cheese Manufacture References Aarts E, Bremmers H, Stemne S. (1997). Melkprijzenonderzoek Wageningen University Netherlands. Boston Consulting Group (1983). Strategy for the Irish Cheese Industry, An Bord Bainne Dublin. Boston Consulting Group, (1993). International Benchmarking in the Dairy Industry, Sydney Bressler, R.G. and King, R.A. (1976). Markets, Prices and Interregional Trade, Wiley, USA. Caraveli, H. and Traill, B. Technological developments and Economies of Scale in the Diary Industry, in A Case Study of Structural Change: The EU Dairy Industry. University of Reading, UK. pp 108 – 127. Commission of the European Communities 1996 The Structure of the European Dairy Industry 1994, Brussels Cook, H.L. and Sprague, G.W. (1968). Irish Dairy Industry Organisation, Dept. of Agriculture and Fisheries. Dublin. DAFF (1990). Agriculture and Food Policy Review, Stationery Office, Dublin. DAFF (1993). Report of the Expert Group on the Food Industry, Dublin. Foley, J. (1993). ‘The Irish Dairy Industry: Historical perspective’, Jour. Soc. Dy. Technol. 46. 4. Gill, J. and Butler, J. (1988). ‘Key Issues regarding a merged Southern Dairy Co-operative and its Potential for Growth’, Conf. Procs., Centre for Cooperative Studies, UCC, Cork. Hay, D.A. and Morris, D.J. (1991). Industrial Economics and Organisation: Theory and Evidence, Oxford Univ. Press. Hayes, I. (1991). ‘Competitive Strategies in the International market for Dairy Products’, Procs. ICOS 1991 National Conference. 21 Economies of Scale and Irish Cheese Manufacture Irish Co-operative Organisation Society (1985). Issues and Options for Irish Dairying, ICOS, Dublin. Irish Co-operative Organisation Society (1987). Strategy for the Irish Dairy Industry, ICOS, Dublin. Igoe, L. (1993). The Irish Dairy Sector - An International Perspective, Goodbody Stockbrokers, Dublin. Irish Farmers Journal (1998) Craig Gardiner Milk Price Audit 1997, June de Jong, H.W. (ed.) (1988). The Structure of European Industry, Kluwer, The Netherlands. Keane, M. and Pitts, E. (1981). A Comparison of Producer Prices for Milk, An Foras Taluntais, Dublin. Keane, M. (1989). ‘Co-operative Amalgamation and Benefits in Milk Processing’, Procs. Conf. on Today’s Challenge for Co-operatives - Effecting Structural Changes, Centre for Co-operative Studies, UCC. Kenneally O, (1996) An Investigation of the Irish Farmhouse Cheese Industry with Special Interest in its Marketing Practices, M.Sc. Thesis, University College, Cork. Krell E and Wietbrauk H., (1993), Die Kosten der Modellabteilung Schnittkaserei am Beispeil der Herstellung von Goude-Kase. Teil 2: Ergebnisse und Interpretation der Modelkalkulationen, Kieler Milchwirtschaftliche Forschungberichte 45, pp 245 - 271 Lynch, S. (1967): ‘Economies of Scale in the Manufacture of Creamery Butter’, Technical Series. 9. An Foras Taluntais. Dublin. McCarthy, J. (1992). ‘History of the Development of the Irish Cheese Industry', Procs. Third Cheese Symposium, National Dairy Products Research Centre, Teagasc, Fermoy. O’Connell L., van Egersat C, Enright P. (1997) Clusters in Ireland, The Irish Dairy Processing Industry, No. 1 Res. Series, N.E.S.C. Dublin O’Dwyer, T. (1968). Determination of the Optimum Number, Location and Size of Dairy Manufacturing Plants, PhD. Thesis. Cornell, USA O’Dwyer, T. (1970). ‘The Structure and Organisation of a Food Industry’, Conf. Procs. Inter Europe - The Challenge of the Food Industry. An Foras Taluntais. Dublin. P. A. (1992). The Food Industry. A Report to the Industrial Policy Review Group. Govt. Publ. Dublin. Pitts, E. (1989). 1992 and the Food and Drink Industry, Stationery Office. Dublin. 22 Economies of Scale and Irish Cheese Manufacture Pitts, E. (1990). ‘Structural Change and Internationalisation in Irish Food Industry', Conf. Procs. The Food Industry in the 1990’s. UCC, Cork. Pitts, E. (1992). ‘Comparative and Competitive Advantage and the Issue of Competitiveness in the European Dairy Processing Industry’, Conf. Procs. Agric. Econs. Soc. Aberdeen. Pitts, E. (1998) European Cheese Industry. It’s Changing Structure and an Exploration of the Extent of Overcapacity. Teagasc, Dublin. Porter, M.E. (1979) How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy. Business Review 47, U.S.A. Harvard Rabobank (1998) The World Dairy Market, Utrecht, The Netherlands. Scherer, F.M. and Ross, D. (1990). Industrial Market Structure and Economic Performance Houghton Mifflin, Boston, USA. Tozanli, S. (1977). European Dairy Oligopoly and the Performance of large Processing Firms, in A Case Study of Structural Change: The EU Dairy Industry, University of Reading, UK. Zwanenberg A. C. M. (1996). European Dairy Co-operatives, Developing New Strategies. PhD thesis, University College Cork, Ireland. 23