Research Reports

AMERICAN INSTITUTE

for ECONOMIC RESEARCH

GREAT HARRINGTON MASSACHUSETTS

July 7

I N

1952

RESEARCH REPORTS

COMING EFFECTS OF CURRENT EVENTS

The Union Shop

Although there have been conflicting reports as to the importance of the "union shop" issue as a stumbling block in the negotiations between the steel industry and the steelworkers union, there is little question that the

"union shop" was at least one of the major issues.

However, there is little indication from any authoritative source as to just what aspect of the "union shop" prevented agreement.

Various Types of Union Shop

Some writers have assumed "union shop" to mean a situation in which only members of the union in good standing may be hired or retained.

1

Others apparently refer to a situation in which all employees in a company must belong to the bargaining unit and pay dues to the bargaining agent but need not join the union. Still others use "union shop" to describe an establishment in which the employers agree to keep only union men on the pay roll; and, although nonunion men may be hired, they must join the union within a certain time. There is also the so-called "preferential union shop" where union members must be given preference when hiring is being done, but where nonunion workers may be hired if union members are not available. The modified union shop, or maintenance of membership, requires that all employees who are at the time of agreement, or who later become, members of the union must remain in good standing as members of the union for the duration of the agreement in order to remain employed.

According to the Wage Stabilization Board, the union's request was that "the present maintenance of membership arrangement be changed to the union shop as authorized by the Labor Management Relations (Taft-Hartley) Act of 1947, as amended. All employees in the bargaining unit [then] would be required, as a condition of employment, to pay to the Union [an] initiation fee and periodic dues."

However, the agreement negotiated by the Pittsburgh

Steel Company provides that new employees must sign applications for union membership and authorizations for dues deductions, but after 20 days and within 30 days, employees may revoke both the application and the authorization by sending registered letters to the company and the union.

iMore often referred to by students of labor economics as the

"closed shop."

105

Arguments for and Against

Various arguments were offered by the union and the steel companies in presenting their views on the union shop to the Wage Stabilization Board.

The union's three arguments were as follows:

(1) The union shop is a prerequisite for union responsibility. When a recognized union does not have full security, it must dissipate its energies in organizing non-union employees and in warding off raids of rival organizations which concentrate on employees who failed to join the recognized union. The Union is required under law to represent all employees in the bargaining unit, whether members or not. In these circumstances, the Union encounters difficulty in maintaining the internal control and direction essential to full responsibility in its working relationship with the management.

(2) The trend in industry generally has been toward the union shop according to studies of the Bureau of

Labor Statistics. Contracts providing for maintainance of membership or merely sole-bargaining recognition are being replaced by the union shop. It is high time for the steel industry to get into line with the rest of

American industry.

(3) The union shop is democratic. A substantial majority of employees—in the steel industry as well as in other industries—want the union shop, as indicated by secret ballots conducted by the National Labor Relations

Board in recent years. Application of the majority-rule principal leads accordingly to the union shop in the steel industry. Union members have every right to expect "free riders," who work beside union members and who benefit from the advances made by the Union, to contribute their share to the costs of Union representation.

The companies' two arguments on the merits of the issue were as follows:

(1) The Union has failed to establish any need for the union shop. The Union's membership has expanded and the Union has acquired security without the union shop. The Union has been accepted by the steel industry; it is financially secure.

(2) The union shop is undemocratic. It limits the right of an individual to decide for himself whether he shall join a union or not. The preservation of minority

Correction: The first sentence of the third paragraph in "The

Harwood Index of Inflation" article published in the June 30

Research Reports should have read "The index of inflation adjusted for inflationary commercial loans (shown by the broken line during 1950-52) increased slightly during May."

rights is essential for democracy, and the union shop ignores the rights of the minority. As long as one man elects not to join a union, his right to refrain from joining deserves the same consideration as that of each man who does join.

A Matter of Principle?

Several industry officials, including Charles Randall of Inland Steel, are reported to be inalterably opposed to the union shop as a matter of principle; the principle presumably being that no man should be forced to act against his wishes.

Two points occur to us concerning this contention.

First, the union argues that the steel companies and their railroad subsidiaries already have made union-shop contracts with the United Mine Workers of America and various railroad unions. If the principle has been abandoned in the particular instances noted, denying the union shop to the steelworkers can hardly be said to be a matter of principle.

A second point, however, seems to us more important.

The loss of a major portion of a worker's personal freedom occurred some time ago in the United States. The

Wage Stabilization Board states, "Thus the fundamental issue concerning individual rights in relation to the privileges of the majority was decided by Congress in 1935; affirmed by the Supreme Court in 1937; and was left unaffected by Congress in 1947, when it passed the Taft-

Hartley Act. On these occasions Congress and the Supreme Court decided that the bargaining agent selected by the majority of employees should and does have the exclusive right to represent all employees in dealing with management concerning wages, hours, and working conditions. In turn, the bargaining agent has the obligation fairly to represent all employees, whether members of the union or not."

It is little wonder that in the present instance the

Board concludes, "If, in the interests of a group of workers, it is not an unwarranted infringement of individual liberty to deprive a person of the right to make his own labor contract, it cannot be an infringement to ask him to lend financial and other support to the organization which bargains for benefits to all employees in the group. The granting of a union shop thus has relatively minor effect, if any, on individual rights under existing law."

The fact of the matter appears to be that the principle of personal freedom was abandoned when the union was allowed to be the sole bargaining agent for all employees.

A Plague on Both Your Houses

How did this power of "sole bargaining agent" come about? Its entire history, its relation to the general trend in the United States away from individual freedom, cannot, of course, be discussed in this article. It seems to us, however, that industry itself is responsible to some extent. Once the early antipathy of employers to labor unions disappeared, or at least was modified; once the employer realized that the union was here to stay; some employers apparently saw the possibility of using the union to their advantage. As long as an employer could bargain with a weak union that represented all the workers, he could readily arrange favorable terms. The simplicity of dealing with a responsible organization rather than with each individual employee clearly was to the employer's advantage. The personal freedom of the individual became of little consequence compared with the advantages of dealing with the union.

It is true that opposition to majority rule for the purpose of determining sole bargaining power was widespread. Nevertheless, we suggest that there were those within management who encouraged the creation of a sole bargaining agent, thus destroying the individual's right to negotiate his own labor contract.

Such industry executives apparently did not foresee the monopoly power that the industrial union now has.

Today, faced with this monopoly power and with the threat of even greater monopoly power through unionshop agreements, some employers now can see more clearly the advantages of personal freedom.

Conclusions

The union-shop issue is another example of the fundamental problem that underlies present-day labormanagement difficulties. Unless and until the problem of labor-union monopoly is recognized and solved, the

Nation presumably will continue to experience crises similar to the steel strike.

106

SUPPLY

Industrial Production

Steel-ingot production, scheduled at 12.3 percent of capacity for the week ended July 5, 1952, was slightly more than that in the preceding week but was 87 percent less than production in the corresponding week last year.

1929 1932 1937 1938 1951 1952

Percent of Capacityf 95* 15 70* 24* 101* 12*p

Weekly Cap. (Million Tons) 1.38 1.52 1.51 1.54 2.00 2.08

Production (Million Tons) 1.31 .23 1.06 .37 2.02 .26

Automobile and truck production in the United States and Canada during the week ended June 28, 1952, was estimated at 125,365 vehicles, compared with a revised total of 129,317 vehicles during the previous week.

1929 1932 1937 1938 1951 1952

Vehicles (000 omitted )t 125 55 121 41 156 125p

Electric-power production in the week ended June 28,

1952, increased to 7,317,817,000 kilowatt-hours from

7,254,058,000 kilowatt-hours in the previous week.

1929 1932 1937 1938 1951 1952

Billion Kilowatt-Hourst 1.72 1.44 2.24 2.02 6.90 7.32

Lumber production in the week ended June 21, 1952, increased. The New York Times seasonally adjusted index was slightly above that for the preceding week and was 2 points above that for the corresponding week last year.

1929 1932 1937 1938 1951 1952

The New York Times Indext 132 39 97 85 108 110 fLatest weekly data; corresponding weeks of earlier years p—preliminary; *holiday

DEMAND

Department-Store Sales

Our preliminary estimate of the seasonally adjusted

June index of department-store sales (based on dollar value) is 3 percent greater than the revised May figure.

(The May figure was 4 percent more than the April figure.) Estimated June sales are 5 percent more than those during June 1951 but are 2 percent less than those during November 1951. From November 1951 through

April 1952, sales had decreased more than 7 percent.

The index of prices of goods sold in department stores decreased slightly during May and was 3 percent below the all-time high reached in September 1951. Consequently, the May index of the physical volume of department-store sales increased 4 percent. The May index was 4 percent more than that for May 1951.

According to preliminary estimates, the potential physical volume of department-store sales decreased 1 percent during May. (The potential-volume series reflects the estimated physical volume of goods available for sale in department stores.) In view of the widening of the gap between the two series in May, inventories may have decreased somewhat. Our other estimates of

May inventories, based on data from 296 department stores and those from New York stores, vary from relatively no change to a 3-percent increase.

The portion of the annual sales made by the major

.departments of a department store remains relatively unchanged from year to year. Detailed data reveal that during recent years the percentages of total sales have been approximately as follows: homefurnishings, 24; women's and misses' ready-to-wear apparel, 2 1 ; women's and misses' ready-to-wear accessories, 20; men's and boys' wear, 12; small wares, 8; piece goods and household textiles, 7; miscellaneous merchandise, 5; and nonmerchandise departments, 3 percent.

Month-to-month changes among the various departments also are of interest. For example, as a percentage of total sales, women's and misses' ready-to-wear apparel consistently reaches an annual low in December, when men's and boys' wear consistently reaches a high.

The seasonal influence of Easter, December, January white sales, and summer furniture sales are all clearly reflected in the month-to-month data.

We have warned readers on previous occasions that, because of the fluctuations of department-store sales from month to month last year, comparisons of weekly sales with those of the corresponding weeks of 1951 may be misleading as an indication of current trends. In order to help readers interpret more accurately the weekto-week reports that appear in various newspapers and in these bulletins, we have calculated that during July an average increase of 5 percent in the comparisons of weekly totals with sales during the corresponding weeks of July 1951 will maintain the seasonally adjusted index at the June level.

The downward trend of department-store sales, which started in December 1951, was interrupted during May and June. Apparently price reductions stimulated sales somewhat during those 2 months. In view of the moderate inflation expected during the remainder of the year, department-store sales may remain near present high levels. Unless further price reductions are made or individuals make extensive use of purchasing media now held idle, we do not expect a substantial increase in sales to occur.

PRICES

Consumers

9

Prices

The Bureau of Labor Statistics' index of prices of goods bought by moderate-income families in large cities increased slightly during the month ended May 15 to an all-time high. The May index was nearly 3 percent higher than that a year ago and 12 percent above the level of prices prevailing at the beginning of the

Korean War in June 1950.

(The Bureau of Labor Statistics compiles and publishes two sets of consumers' price indices, designated the "old" and "new." Until the final revisions of the new index are made, the index discussed in these bulletins will be the "old" series.)

The May increase was attributable to slight increases in the prices of foods, miscellaneous goods and services, and residential rents, which more than counterbalanced minor decreases in the prices of apparel, fuel, electricity and refrigeration, and housefurnishings. (The weight given to food, miscellaneous goods and services, and rents in the Bureau's over-all index is nearly three times that for apparel, housefurnishings, and utilities.) Since their respective 1951 highs, changes in the various components have been as follows: apparel, down 3 percent; housefurnishings, down 2 percent; foods, down nearly 1 percent; fuel, electricity, and refrigeration, virtually unchanged; miscellaneous goods and services, up 1 percent; and rent, up nearly 2 percent.

A break-down of the consumers' price index into its major components reveals two different price trends during the last 6 years. Prices of nondurable goods such as foods and apparel fluctuated greatly. On the other hand, prices of miscellaneous goods and services, fuel, electricity, and refrigeration, and residential rents have increased steadily. Food prices increased 55 percent from March 1946 through August 1948, decreased

11 percent through February 1950, and thereafter increased 20 percent to an all-time high in January 1952.

Apparel prices fluctuated in a more or less similar pattern. The price trends of both miscellaneous goods and services and fuel, electricity, and refrigeration increased more or less steadily during the last 6 years, although the rate of increase slackened somewhat during the period when prices of foods and apparel decreased. Residential rents rose sharply in 1947 and since then have increased gradually.

•26 "27 -'88 | "29

L I A B I L I T I E S OF COMMERCIAL FAILURES

In its June 1952 issue, Fortune magazine published a survey comparing retailers' list prices with prices actually paid by consumers. According to the survey, prices paid by consumers for radios, television sets, and appliances in most large cities were about 20 to 35 percent less than the list prices suggested by manufacturers. Only 10 percent of the retail sales of these goods were at list prices. This provides further evidence of the inadequacy of the consumers' price index. We have emphasized many times that the consumers' price index does not measure changes in the prices actually paid by consumers because reporters for the Bureau of Labor

Statistics record only regularly quoted or list prices.

"Irregular" or "special sales" prices and discounted list prices are not used. In view of the widespread use of discount houses as retail outlets, there is little question that the consumers' price index is not accurately measuring changes in the prices actually paid by consumers.

Moderate inflation during the remainder of 1952 may prevent a major decrease in consumers' prices during those months. However, in view of the deflation expected in the first half of 1953, we believe that a significant decrease in prices may occur at that time. Whether^ or not these changes will be reflected in the consumers' price index remains to be seen.

Commodities at Wholesale

1951

(August 1939 = 100)

Spot-Market Prices

July 2

339

(28 basic raw materials)

Commodity Futures Prices 378

(Dow-Jones Daily Index)

1952

June 26 July 2

294 , 293

369 369

BUSINESS

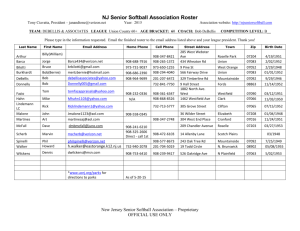

The Trend of Commercial Failures

The liabilities involved in commercial failures during May totaled $21,193,000, about 28 percent less than those during April and 10 percent less than those in the corresponding month a year ago.

The number of failures in May was 638, compared with 780 in April and 755 in May 1951. During the first 5 months of 1952 the number of failures was 3,423, compared with 3,554 failures in the corresponding period of 1951. The average amount of liabilities involved per failure thus far during 1952 has been $36,-

600 and during the previous 3 years was as follows:

1951, $32,290; 1950, $27,100; 1949, $33,300.

The series shown on the accompanying chart is a 3month moving average (plotted at the midmonth) of

108

4

49 '50 '51 52 commercial-failure liabilities. The April average increased 2 percent to a level 37 percent above the average for April 1951. The downward trend that started in October 1951 was reversed in January, and through

April the average had increased 26 percent.

A break-down of liabilities of failures reveals that the percentage decreases during May were as follows: wholesale trade, 57; construction, 3 1 ; commercial services, 30; retail trade, 25; and manufacturing and mining industries, 19.

The inverted series of seasonally adjusted liabilities of commercial failures is one of the indicators of cyclical changes of business activity; the series usually leads cyclical peaks of general business activity by an average of 10*/£> months and leads business troughs by an average of 71/3 months. This series apparently started an upward trend late in 1951, which suggests that the recent minor business recession may be interrupted, temporarily at least.

According to the June issue of the Survey of Current

Business, the Nation's business population at the end of

March 1952 was 4,018,700 firms, slightly more than the total of a year ago and a few thousand more than the previous postwar peak reached in June 1948. Changes in the number of firms during the past year have been as follows: transportation, communication, and other public utilities increased nearly 5 percent; contract construction increased 3 percent; wholesale trade and finance, insurance, and real estate increased 1 percent; and retail trade decreased 1 percent. The number of firms in the service industries and in manufacturing was unchanged. However, among the manufacturing industries, durable-goods manufacturers increased 4 percent; nondurable-goods manufacturers decreased 4 percent.

The report reveals that "In December 1947 the number of manufacturing firms was close to the postwar high which had been reached in June of that year. In

September 1951 most of the manufacturing groups were below December 1947 with the larger relative declines occurring in food; apparel; leather; chemicals; stone, clay and glass products; transportation equipment; and miscellaneous manufactures."

The 3-month moving average shown on the accompanying chart may decrease during May and June as the liabilities during June and July replace relatively larger

March and April liability figures in the calculation of the average. A continuation of this downward trend later in the year would be an indication of improving business; a reversal of the trend would suggest future economic difficulties.