31295015242083 - Institutional Repositories

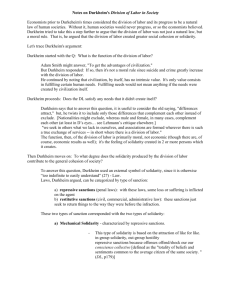

advertisement