The eight essential supply chain management processes

advertisement

INTEGRATION

PERFORMANCE

COMMUNITY

EXECUTION

FRAMEWORK

y

THE EIGHT ESSENTIAL

The Global Supply Chain Forum

of The Ohio State University has

identified eight processes that form

the foundation of supply chain success.

The challenge is to integrate these

processes both internally and externally

with key partners in the supply chain. Two of

those key processes — customer relationship

management and supplier relationship management — help companies accomplish this integration

and realize the revenue and profitability gains that

inevitably follow.

James O'Brien

18

CH\!N

^I^\.\c;EME^r

2004

SUPPLY CHAIN

MANAGEMENT

PROCESSES

By Douglas M. Lambert

u c c e s s t ti I sup ply c h a i n m a n age ni e ti tthe term- Many people consider it to be synonunotts witb

requires cross-functional integration of key logistics or with logistics tbat also includes customers and

business processes within the firm and suppliers. Others view supply chain management (SCM) as

across the network of firms that comprise the new tiame for purchasing or operations—or the eomhinatbe supply chiiin. It is focitsed on relation- tion of purchasing, operations, and logistics. Increasingly,

ship miinagement and the performance however, executives in leading companies are recognizing

improvements that result. In many compa- supply chain management as the management of relationnies, however, executives struggle to ships across tbe supply ebain. They view SCM in terms ot

achieve the necessary integration and, consequently, the business process excellence and as a new way of managing

resulting improvements. The problem is that they don't fully tbe business and the relationships with other members of the

understand the supply chain business processes—and the supply chain.

hnkages necessary to integrate those processes.

In this article, we adopt tbe following definition of SC,\1

Drawing from work done by The Global Supply Cbain developed by tbe Global Supply Chain Forum: Supply chain

Forum, this article identifies the eight processes tbat need to management is the integration of key business processes from

be managed and integrated for successful supply cbain man- end user through original suppliers that provides products, seragement. (For more on (he Global Supply Chain Forum, see vices, and information that add value for custo»iers and other

tbe sidebar on page 21.) Two of tbese processes provide tbe stakeholders.

linkages rcqitired to facilitate integration among the supply

This view ot supply chain management is illustrated in

chain members to coordinate tbe otbcr processes. These two Exhibit I. It depicts tbe following: a simplified supply chain

ke\ linkages are customer relationship management (CRM) network structure of a manufacturer with two tiers of cusand supplier relationship management (SRM).

tomers and two tiers of suppliers; tbe related information and

produet

flows; and tbe eigbt supply cbain management

By understantling the key supply ebain management

processes

that must be implemented witbin organizations

processes—and recognizing why and bow tbey should be

integrated—supply cbain managers ean sueeessfully position across the supply cbain. All of the processes are cross-functional and cross-organizational in nature. Further, as the

their companies for higher reventies and prolitahility.

exhibit illustrates, every organization in tbe su|)ply cbain

needs lo be involved in tbe implementation of tbose processJust What Is Supply Chain Manageuient?

es.

But at tbe same time tbe exbibit shows tbe corporate silos

IJelore [irocccding, it's inifiortant to define supply chain manat

ibe

top, wbicb can work against tbis integration.

agement beeatise theres still a great deal ol contusion over

In reality, of eotirse, a supply cbain is mucb more cotiiplex tban tbe row of silos de|)icted in Kxbibit I. For a comDouglas M. Lambert is the Rtjymond H. Mason Chair in

pany

in tbe middle ol the supply cbain, tbe supply ebain

Transportation cintJ Logislics and Director of The Global Supply

looks more like an uprooted tree (see Exbibit 2) wbere the

Chain Forimi al the I ishfr College of Business, ihe Ohio State

roots represent ibe supplier network and tbe brancbes repUniversih'. This article is adapted j rum his new hooh Supply

resent tbe customer network. Moreover, tbe supply cbain

Chain Managcmciil: Proct'sst's. Partnerships, Performance

will look differently depending on a company's position in it.

(Supply Chain Management Institule, 2004). Far more in/orFor example, in tbe case ol a retailer, like Wal-Mart, tbe

mation, visit u'ww.sem-institutf.org.

S

Suppi^

CHAIN

MANACEMEIVT

R h v n u

• SipirviUKn

2004 1 9

Processes

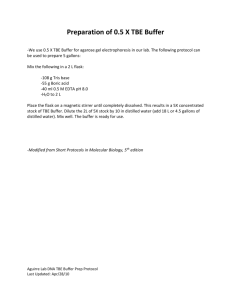

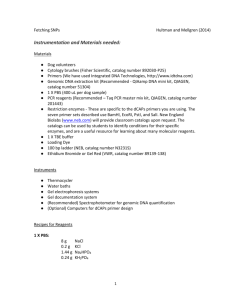

EXHisrr 1

Supply Chain Management Players and Processes

Information Flow

Customer Relationship Management

Customer Service Management

Demand Management

Order Fuifiliment

Manufacturing Flow Management

Supplier Relationship Management

Product Development and Commercialization

conciuded that they cannot

optimize product Hows without first i m p l e m e n t i n g a

process approacb to tbe business. Yet while s e v e r a i

authors have suggested implementing business processes

in tbe context of suppiy cbain

management, tbere is not yet

an "industry standard" on

what tbese processes should

be. Tbe value of baving standard business processes in

plaee is that managers from

organizations across the supply chain can use a common

language and can link up

their companies' processes

with tbosc oi the other supply

ebain members.

Returns Management

Tbe eigbt key supply cbain

management processes identified by members oi Tbe

Source: Adapted from Douglas M Lambert, Martha C. Cooper, and Jarus D. Pagh, "Sjpply Chain Management: Implementation Issues and

Global Supply Cbain Forum

Research Opportunities,' The InternalionalJournal of Logistia Management, Vo\.'), No. 2 (1998), p. 2.

(as shown in Exbibit I) are:

end consumers would also be the "tier-1 customers" next to

• Customer relationship management.

the dark square in the center (indicating the iociil company,

• Customer service manageirtent.

Wal-Mart).

• Demand management.

Managing the entire supply chain—that is. managing ail

• Order fuifiliment.

suppliers baek to the point of origin and all products/serviees

• Manufaeturing flow management.

out to the point of consumption—<;an be a daunting task. So

• Supplier relationship management.

most exeeutives tend to Foeus on managing their supply

• Product development and cummerciali/ation.

chains to the point oi consumption. The reasoning here is

• Returns iiianagcment.

that whoever has tbe relationship with tbe end user has tbe

Customer Relationsbip Management, ihe CM^M process

power in tbe supply ehain. Intel, for example, created a rela- provides the structure lor how reiationsbips with eustomers

tionship with tbe end user by having computer manulactur- are de\'elopcd and maintained. Throtigh this process, maners plaee an "Intel inside" label on their eomputcrs. This posi- agement identities key customers and ctistomer groups to be

tioning also affects the computer manufacturer's ability to targeted as part of tbe firm's business mission. Ibe goai is to

switch microprocessor suppliers. Yet while most of tbe focus segment eustomers based on their \alue ()\er time and to

to date has been downstream, opportunities exist to signifi- increase customer loyalty by jiroviding customized products

cantly improve profits by managing the upstream sLi|iplier and services appropriate to tbe particular value proposition.

network as well.

Leaders in this process create cross-lunetional customer

teams

to tailor product and serviee agreements (PSA) that

At the end of tbe day, a supply ehain is managed link by

meet

the

needs of key aecoimts and customer segments and

link, relationship by relationship. And tbe key linkages in

document

how the two firms will engage in business. Tbe

all ol these activities are formed by tbe customer relationi-'SAs

sjiecily

levels ot perlormance lor the lirm. They also

sbip management (CRM) process of the seller organization

provide

the

hasis

for jierformance reports thai measure the

and the supplier relationship management (SHM) process

profitability

of

individual

customers as weli as the firms

of ihe buyer organization. C R M and SHM are tbe tools the

financial

impact

on

(he

customer's

financial periormance.'

supply ehain manager uses to bring tbe eigbl key processes

CRM

teams

will

then

work

wiih

key

customers to improve

togetber.

processes and eliminate demand variability and nonvalueadded actixities.

The Eight Key SCM Processes

Suecesslul supply ebain management re(|tiires a cbange from

managing indi\iclual lunctions to managing a set oi integrated

processes. In many leading corporations, management bas

2 0

Suppi.i

C H A I N

M A N A C : I; M K N T R I - V I K W

• S n - r r M H I n

2 0 0 4

Customer Service Management. Ibe customer service

management process represents tbe company's faee to the

customer. It is the key point ot contact for administering the

www. scmr. com

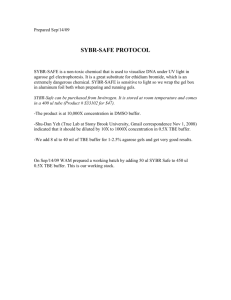

EXHIBIT 2

The Supply Chain Network Structure

Tier 3 lo

Initial

Suppliers

Tier 3 to

Tier 2

Suppliers

Tier 1

Suppliers

Tier 1

Customers

Tier 2

Consumers/

Customers End Users

and coordinated witb key suppliers and customers. Tbe

objective is to develop a seamless system frotn tbe supplier to

the firtii, and iben on to the various customer segtnents.

Manufacturing Flow Management, Manufacturing flow

management includes all activities necessary to obtain,

implement, and tnanage manufacturing flexibility in tbe supply cbain and to move products through tbe plants. Ibe ability to make a wide variety of products in a timely manner at

tbe lowest possible cost is a reflection of tbis process, 'lo

acbieve tbe desired manufacturing flexibility level, planning

and execution must extend beyond tbe four walls of tbe manufacturer and oul to tbe supply cbain partners.

Supplier Relationsbip M a n a g e m e n t .

Focal Company

Members of the Focal Company's Supply Chain

Source: Adapted from Douglas M. Lambert, Martha C. Cooper, and Janus D, Pagh,

"Supply Chair Management: tmplemeniation [S5jt5 arid Research Opportunities,'

The Internat'ionalJournal of Logistics Management,Vo\. 9, No, 2,1998, p. 3,

PSAs developed by customer teams during tbe customer relationship managemetit [process. Customer service provides the

customer with real-time information on [lromised shi[i|Mng

dates and produet availability through ititerfaces with stich

lunctional areas as manulacturing and logistics. Tbe customer service process may also include assisting the customer

witb protltict ap|)licatiotis.

Demand Managemetit. DemaiKl management is the

process tbat balances customer re(.|uirements witb sitpply

cbain capabilities. With tbe right process in place, management can matcb supply with demand proactively and execute

the plan wilh minimal disrtiptions. It is important to note

that this prcjcess is not limited to forecasting. It also includes

synchronizing supply and demand, increasing llexihilJty, and

reducing variability. Demand management entails controlling

all of those practices that increase demand variahility, including end-of-qtiarter loading and terms of sale that encourage

volume btiys. A good demand management system uses

point-of-sale and key customer data to reduce uncertainty

and provide efficient flows tbrougbout the supply ebain. It

also effectively coordinates marketing retpiirements and |irodtiction [ilans.

Order Fulfillment. Ihis suppK chain |>rocess involves

more than just tilling orders. It also eneompasses all activities

necessary to define customer re(;|uirements. design a network, and enable a firm to meet customer retjuests while

minimizing tbe total delivered cost. While tnttch of the actual

order ftilfilhneiit v\ork will be performed by tbe logistics function, the process needs to be implemented cross-functionally

www .scnir.torn

Ibe SRM

process

provides tbe structure for bow relationsbips witb suppliers

are developed and maintained. As tbe name suggests, tbis

process is a mirror image of customer relationsbip management. And as is tbe case for CRM, it involves developing

close relationsbips wiib a small subset of suppliers based on

tbe value tbat tbese suppliers bring to the firm over time.

Note tbat tbese are long-term relationships tbat provide winwin outcomes for botb parties. For eacb key supplier, tbe

firm should negotiate a |)roduct and service agreement tbat

defines tbe terms of the relationsbip. For less critical suppliers, tbe firm sbould follow tbe more traditional approacb of

simply providing tbe PSA, which iti most cases would he

non-negotiable. In sbort, supplier relationshi|) management is

abotit defining and managing tbese PS.As,

Product D e v e l o p m e n t and Commercialization.

Ibis sup-

ply cbain management process provides tbe structure for

working with customers and suppliers to develop products

antI bring them to market. F^^lfective itnplementation of tbis

process not only enables management to coordinate tbe efficient flow of new products across tbe supply cbain but also

bel[)s otber members of ibe supply cbain to ramp up matitifacttiring, logistics, marketing, and other activities necessar\'

to support product commercialization. A product development and commerelalization process team would work with

CRM process teams to identify ctistomer needs (botb articu-

The Global Supply

Chain Forum

The Global Supply Chain Forum of The Ohio State

University is a group of noncompeting firms and a team of academic researchers that has been meeting regularly since 1992.

The group's objective is to improve the theory and practice of

supply chain management.

The member companies of the Global Supply Chain Forum

ar-e 3M, Cargill, The Coca-Cola Company, Colgate-Palmolive

Company, Defense Logistics Agency, H e w l e t t - P a c k a r d

Company, I n t e r n a t i o n a l Paper, L i m i t e d Brands, Lucent

Technologies, Masterfoods USA, fVloen Inc., Shell Global

Solutions I n t e r n a t i o n a l B.V., Taylor Made-adidas Golf

Company, and Wendy's International.

M AN A ( i i

.VI h \ r

Ri.viKW

• SFLPTF:MBI.H

20(14

21

Processes

hiR'd iiiid uniirliculalL'd), willi ihf SRM [M-OCCSS tciims lo

select tnaterials and suppliers, and wilh ihe manLikicturinj;

Flow maniiuement process team to develop prodLiction [(.'clinology appropriate to the prodiiel/inarkel fomhination.

Returns Managetnent. Rett.rrns nKiiuijj,emenl is ihc process

l)\ uhicli acli\ilic's associaled with returns, reverse logistics,

"giitek(.'epi[ig, ciuil return avoidance are managftl within the

firm and aeross key members ol the sii|)piy ehain. Avnidanee.

whieb is a key jsart of this process, involves finding ways to

minimize the numher of return requests. It ean include

ensuring that the [iroduct s t|uality iintl user Iriendliness are

at the liighest attainahle level before the [iroduct is sold antl

shipped. Avoid.ince could also entail changing promotional

[jroj^rams that load the pipeline when there Is no realistic

chiince that ihe |ir(xluet shipped will be sold. Properly implemented, then, the returns management process enables firms

not only to manage the reverse product How ellieiently hut

also to identify opportunities to reduce UTiwanted returns and

to eontrol reusable assets such as containers. Effective

returns management is an important part ol SCM and provides an opportunity to achieve a sustain a hie competitive

advantage.

Kach of the eight sup|i!y chain maniigemcnt processes hiis

hoth strittegic and operational elements—that is, a strategic

element in which the firm establisbes and strategically manages the process and an operational element in whieh the

lirm executes tbe process. The strategic elements should he

led by a management team eomprised of representatives from

multiple fimctions ineluding marketing and sales, finance,

produetion, [purchasing, logistics, ami research and develo|)meiit. This team is res|)onsihle lor tlexeluping the proeedures

at the strategic le\el and seeing that they are implemented.

I h e strategic leam also identifies how the external partners

will he integrated into the supply chain. The operational

eomponent of eaeh proeess. v\here tlie day-to-tia) acti\itics

take plaee. is exeeuted h\ the managers within eaeh lunetional area.

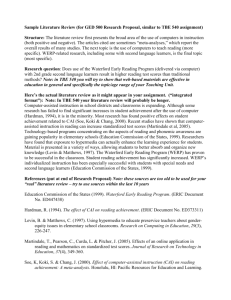

Lxhihit ^ shows how ihe husincss kmctions within the

organization provide input to the eight supply chain management proeesses. In the customer relalionship management

process, for example, marketing and sales pro\'idcs the

aecount management expertise, engineering provides the

spccilieations, logistics provides knowledge of logistics and

customer service eapahilities, manulacturing provides the

manulacturing ea|iabilities, purchasing provides knowledge of

sujjplier capabilities, and iinance provides customer profitahihty reports. Customer service requirements must he factored into ihc manufacturing, sourcing, and logistics inputs.

Customers and suppliers are shown as hookcnds on the

exhibit to reinforce the point that each ol these processes, to

he properly implemented, requires the in\()lvemcnt of customers and suppliers.

CRM and SRM: The Critical Linkages

Customer relationship management and supplier relationship management provide the critical linkages throughout

EXHiBrr3

Functi anal Input to the Supply Chain Proce SS

Business FunctionsH^

Marketing &

Sales

Research &

Development

Logistics

Production

Purchasing

Finance

Account

Management

Requirements

Definition

Logistics

Capabilities

Manufacturing

Capabilities

Sourcing

Capabilities

Customer

Profitability

Account

Administration

Technical

Service

Performance

Specifications

Coordinated

Execution

Priority

Assessment

Cost to

Serve

Demand

Planning

Process

Requirements

Forecasting

Manufacturing

Capabilities

Sourcing

Capabilities

Tradeoff

Analysis

Special

Orders

Environmental

Requirements

Network

Planning

Made-to-Order

Capabilities

Material

Contraints

Distribution

Cost

Manufacturing Flow

Management

Packaging

Specifications

Process

Stability

Prior ttization

Criteria

Production

Planning

Integrated

Supply

Supplier Relationship

Management

Order

Booking

Material

Specifications

Inbound

Material Flow

Integrated

Planning

Supplier

Capabilities

Total

Delivered Cost

Product Development

& Commercialization

Business

Plan

Product

Design

Movement

Requirements

Process

Specifications

Material

Specifications

R & D Cost

Returns Management

Product

Lifecycle

Product

Design

Reverse

Logistics

Remanufacturing

Material

Specifications

Revenue &

Costs

Business Processes

f

Customer Relationship

Management

Customer Service

Management

Demand

Management

2

Order Fulfillment

"a.

Q.

^

2 2

S l I M ' M

C l l \ l \

M A N A C K M I N V

R i V l l V V

• S l . P I F M R I R

2 0 0 4

Manufacturing

Cost

^

S

c

o

=

www ,S(.'nir,i'i)m

Processes

IIK' sLipply ch.iin. As dcpiLlctl in Exhibit 4, ior (.-ath siipplicr

in the supply chain the ulUmalc measure ol suecess ot the

CRM process is the change in profitahility of an individual

customer or segment ot customers. Por each fiis/oii/cr. the

irue nifasurc of success of the SRM process is the impact

thai a supplier or supplier segment makes on that eustomer's

[irolitahility. ( \ ' o t e ihat in eases where commodities or

undiffercntialcd components are heing bought for inclusion

in another product, it makes more sense to do a total eost

report than a specific profit-and-loss statement for each

commodity/component.) The goal is to increase the joint

profitability by de\'el<)ping the relationship. Accordingly, the

overall performance of the supply chain is determined by the

combined improvement in prolitability ol all nii'mbers Irorn

t)ne year to the next.

EXHIBIT 4

CRM and SRM:The Critical Linkages

Supplier

D

Manufacturer

C

P&L

for C as

Customer

Total Cost

Report

for D as

Supplier

Wholesaler/

Distributor B

P&L

P&L

for B as for C as

Customer Supplier

Retailer/

End User A

P&L

P&L

for A as for B as

Customer Supplier

Let's begin by eonsidering the CRM linkage. Companies

typically spend large sums ol moncv' to attract ncv\' customers, ^et these same eomjianies often are complacent

when it comes to nurturing and strengthening relationships

with existing ctistomcrs.- In most cases, hov\cvcr. existitig

customers rcjiresent the best opportunities ior prolital^lc

growth. In faet, studies sbow strong, direct rciationsbips

between prolit growth and customer loyalty, eustomer satisfaetion, and the value of goods delivered to customers.^ CRM

|ii'o\ ides tbe structure lor leveraging

tbcsc t|ualitics and evaluating tbc prolitability—and potential profitability—

ol indiv idual eustomers. Aeting on tbis

evaluation, cross-lunctional customer

teams can taihir product and service

agreements to meet the needs of key

accounts and customer segments."^

related to trans|iortation incltitling deli\eries, order minimums, driver instructions, will-calls, and appointments; billof-lading instructions; pallets to be used; purchase-order confirmations; order-status information: details related to prieJng

inquires; availability of market-development funds; marketing

promotional allowances; acceptability of haek orders and bow

tbey will be handled; and contract terms.

Supplier relationship management is the mirror image oi

cttstomer relationship management. Remember that all suppliers are not the same. Some contribute more to a firm's

profitability than others. Its important to ha\e en)ss-functional teams that interact elosely with these high contributors. Tbe strategie relationship sbould be led by a management team responsible for developing strategies and seeing

tbat they are implemented. At tbe operational le\el. teams

are established for each key supplier and for eaeb segment of

nonkcy, or less eritiea!. suppliers. I'hese teams are eoniprised

of managers from several funetions, including marketing,

finance. R&D, produetion, purehasing, and |{)gisties. While

employees who arc not members ol the S H \ ! teams may he

involved in e.Kecuting the activities, the teams maintain overall managerial eontrol of the process. (I he same holds true

for the CRM |iroeess,l

Criven the current emphasis on business etbies, both the

C'R.M and SR\f teams need to have an agreement up Irorit

on what lypes ol data will be shared. Teams need to be mindlul ol the line line betv\een using proeess knowledge vs.

using specific competitive marketing knowledge gained from

a ctistomer or supplier. In a similar vein, individuals should

not he put in a position where they are working on teams

involving competing suppliers or eustomers. The reason; Its

iust too diilicult to kce[i the tv\)) sets of relationships and

PSA tliscussions separate and distinct.

lSup|ily ehain managers shouki note that CRM ami Sf-{M

themselves have seveii subprocesses, which are not addressetl

in this artiele. These subproeesscs are dillercntiating CLIS-

Profitability reports that capture all

of the costs and revenue implications

of a relationship are the key to tracking supply

PSAs document how the two firms

will engage in business- For key customers, llie PSAs are customized; for segments of otbcr Ltistomers, stantlard values arc

used for each element of the agreement. PSAs come in many

forms, both formal and informal, and mav be referred to by

different names from company to company, fo achieve the

desired results, however, they need to be lormali/ed as written doctiments. 3NT for example, has comprebensive, written

PS,\s that inelude tbe following: eontaet information ineluding name, tide, telephone number, and e-mail address lor

both .-^M and tbe customer representatives; all ol tbc details

2 4

S L I'I'M

(.' II VI \

\1 V \ \(.l

M I \ I

I! I V I

I I \ l l i l li

2004

chain process improvements over time.

tomers/su[)(iliers; preparing the account/segment management

team; internally reviewing tletails related to the business conducted; identifying opporttmities lor sales grov\th, eost reduction, and service improvements; developing the product and

service agreements; implementing the product and ser\iee

agreements; and measuring performanee and generating profitability reports and total cost reports as appropriate.)

In addition to linking partners across tbe sufiply cbain, the

CR.M and SRM processes coordinate each of the other si.x

processes. Any improvements made in these processes are

in customer iind su|>[ilii_'r |ir<iliLal)ility rcpiirts. For

il the CRM and SRM Icjiiis idcnlily an opportunity

t(t imiinnc' pcrlormancc by focusing on demand management,

the\' iTihirm the demand management process teams from the

two companies. If those teams do impro\c the demand management proeesji, then product availability imprcnes—which

increases revenue for the customer and the supplier. In addition, better demand planning could reduce inventories, thereby

lowering tbe inventory- cam-ing cost cbarged ro the customer's

profitability report. There also may be fewer last-minute production changes and less expediting ot inbound materials,

which will decrease the costs assigned to each customer. For

these improvements to he realized, measurements must be in

place to motivate and compensate team members.

Having aceurate customer prolitability reports is tbe key to

tracking these kinds of process improvements. These reports

enable the CRM process teams to traek performance over time

across all of the supply chain processes. Good profitability

reports relleet all of tbe cost and revenue implications of the

relationship. Variable manufacturing costs are deducted Irom

net sales to calculate a manufacturing contribution. Next, \ariable marketing and logistics costs, such as sales eommissions,

transportation, warehouse handling, special packaging, order

processing, and account receivable cbarges, are deducted to

calculate a eontribution margin. Assignable nonvariable costs,

sueb as salaries, customer-related advertising expenditures,

slotting allowances, and inventory' carrying costs, are subtraeted to obtain a segment-controllable margin. Tbe net margin is

obtained after deducting a charge for dedicated assets. These

statements contain opportunity costs lor in\estment in reeeivables and inventory' as well as a charge for dedicated assets, in

this sense, tbey are much closer to cash-flow statements than a

traditional profit-and-foss (P8rL> statement.

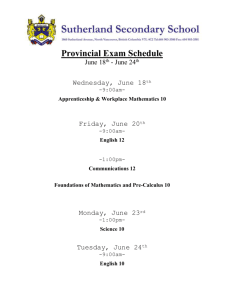

EXHIBIT 5

Sysco Sales and Earnings History

Sales

(Billiors)

Net Earnings

(Millions)

30

5 Year CAGR:

Sales = 11.3%, Net Earnings = 19.1%

25

10 Year CAGR:

Sales = 10.1%, Net Earnings = 14.5%

20

20 Year CAGR:

Sales = 14.6%, Net Earnings = 16.0%

15

Sales

800

J

^ ^ Net Earnings

/^

700

jj

600

/ /

500

1

400

•^

200

5 100

0 '70

^""^""^^^^

'75

'80

'85

'90

'95

'00

0

'03

Source: Neil Theiss, senior director, Supply Chain Management, Sysco Corp.

[lating member of tbe Global Supply Chain Forum, offers a

good example of bow tbis can be done effectively. I his international provider ol food and agricuftural products worked

vvitb a key customer to develop a method for sbaring sup|ily

ebain benefits tbat inct)rporated tbese elements:

• An agreement in principle on a fair allocation ol benefits. (Sbouid it be 50/50, 60/40, or some otber breakdown?)

• A timeframe for benefit sharing. (Sbouid it be for tbe

fife of tbe agreement, for five years, or re-assessed annually?)

• A decision on w bat benefits/costs to include.

• A fair apjiroacb to bandling ca[iital expenditLire costs.

• An accurate baseline to use as a starting point lor measuring sav ings.

• A comm{)n process to measure value captured.

Sysco, a $23.4 billion food distributor, began implement• A benefit reviev\ and approval procedures,

ing profitability reports by customer In \9'~)9 with great suc• A mechanism to accrtie and transfer value Iwbere, how,

cess. Tbcse reports bave enabled management to make

how often, and so forth).

strategic decisions about the alloeation of resources to

• A methodology re\iew.

accounts, f he li\t'-year cumulati\e annual growth rale

The process improvement teams from both companies

(CAGR) for the period 1499 to 2003 was 1 1.3 pereent for agreed that benelits deri\ed from su]ipfy cbain initiatives

sales and 19.1 percent for net earnings. As sbown in Exhibit must f)e explicitk' recognizetl in supply cbain project outS, net earnings growth improved shar|ily after the [jrolitahility comes (l(jr e.xamplc. redtieed freigbt. iov\er invcntorv-earr\ ing

reports were im|ilcmented.

costs, and redueed transaction costs). Additionally, tbese

benelits must be in excess of a pretfetermined baseline for

One Success Story

each area. They ftirther agreed that the costs to f)c considManagement should work to implement proeess improve- ered sfiotifd (I) directly relate to recommended stippK chain

ments that increase the profitability ol tbe total sup|ily cbain, initiatives (capital costs, transaction costs, system-related

not just tliat ol a single firm. This means encouraging actions costs, and so lorth); (2) the addition or deletion of fuli-time

that henefit the entire supply chain while, at the same time, employees (not the increase or decrease in the v\orkload of

etjuitably sharing the risks and the rev\ards. It's especially existing employees): (3) be greater than an agreed-iipon miniimportant lo develop clear guidelines fOr sharing tbe rev\ards. mtim dollar amount: and i,4l be ftilK' ditcumentcd. I he two

If any one of the parties perceives that its not gaining any- companies decided that a 50/50 split ot benelits was in keepthing from the process improvement efforts, it v\ill be diffi- ing with the overall partnership. Plus, they lelt that this

arrangement wotild motivate botb [larties tcj maximize tbe

cult to obtain tbat party's full commitment.

The CRM and SRM teams must (|uantif\- the benefits of opportunities vvbile acknowledging that neither partv eould

process improvements in financial terms. Cargill, a partici- have achieved the savings without the other.

Su I'!• I Y CIIVI \ M

\ I Rl \ I I W •

SFL

P T l M II I I! 2 0 0 4

25

Processes

Ciirgill's manajtcmfiU hdicxcd thai it was Importaiil ti> idcntiR- the ran^f ol llu' cApcelations that each icani hroiight to the

project. This would help hoth parties reach iifirt'cmcni on realistic and nuitLKilly henefieial ohiecti\es in sueh areas as proeess

elliciency, growth/proiit stabilit\'. c{)sts savings, improxed customer senice. orjiuni/ational alif^nmcnt, and mclrics.

thus improving per-unit [inilitahilit). Six \cars later, the manufacturer had not seen the anticipated inventory reductions

and redueed the serx'iee promise to 48 to 72 hours. Vel the

reason llial the rapid delivery system never aehie\ed its lull

potential was that the manufaeturers sales and marketing

organization was still |iro\iding eiistomers with ineentives to

The key lessons learned Irom Cargills e.xperience can he hu\ in large volumes.'' ()])\ iously, the husiness proeesses ol

this company were nol integrated and coordinated.

summarized as lollows:

• Gain sharing agreements need to he tletcrminctl at the

This example should make it clear that lailure to manage

outset so that it doesn t untlermine the accomplishment of all the touehes hetween suppk chain partners will diminish

the joint oh|eeti\cs.

the impaet of any suppK chain in[tiati\e. Conversely. im|ile• Working het\\ecn internal husiness units is (.hallenging menting the eight sLip|ily ehain management [processes

enough. \ \ hen yoti add into the mix cxtei'na! trading partners, iiiereases the likelihootl of success because all kmctions as

the challenge intcnsilies hecaiise ol issues ot trust, eulture. well as all key eustomers and suppliers—v\ill lie involved in

tbe initiative's planning and im|'>lementati{>n. This was corjirocess, and systems Cii|iahilily.

rob{)rated

at tbe Spring 2004 meeting oi Ibe Cllobal Supply

• Skeptics ahounti; success ret]Liires tocusetl leadership

C'bain Forum, wliich featured a series of breakout sessions

and management support.

• Partnerships work; they may take a while to develop, devoted lo tbe topic. ""Ihe Supply Chain of the Future," At

hut they work. Once trust is established, hoth ]iartics will the entl oi the day, the group concluded that if an organization can sueeessfully implement all eight of the processes, it

lind numy opportunities to learn Irom eaeh other.

• Hvcrynnc involved in this initiative enhanced their will have reaehed that supply chain of the luture and he ah!e

knowledge and capabilities, which will pni\e ad\antageous in to respond to whatever ehallenges the husiness might laccfuture initiatives.

As reflected in the Cargill e\aniple. the eustonier relationship management and supplier relationship management

processes do a numiier of important things at the strategic

level. Specifically, they identify eustomer and supplier segments, provide criteria for categorizing customers and suppliers, provide teams with guidelines for cust(jmi/ing product

and senice offerings, dexelop a iramework for metrics, antl

offer guidelines for sharing process improvement benefits. At

the operational level, these processes mainly focus on writing

and implementing ihe prncluet and seniee agreements.

How Are You Doing?

Failure t(i ini|ilenient those cross-functional business

prueesses can also result in missetl ojiportunities antl poor

decisions. I h e following real-lile example illustrates the

point. A manufacturer of consumer durable goods implemented a rapid deli\'ery system that pro\ided retailers with

deliveries in 24 to 4S hours anywhere in the United Slates.

The system was designed to enable the retailers to im|iro\e

seniee to their consumers while holding less in\enlor\ and

S L' iM'i \ C n \i N M \ \ M : I \ n \ I Ri v i f vv • S [^

Author's note: Ihe uuthoT ivuidd tike- to acknowledge the contrihuliiiii nj ihe members oj The Gloha! Sitpfyh (^Jiaiii Foniui at

I lie Oh'id State University whose practice, iiisii^ht. idens. mid

conniicnts hai'c cinitvibutcd sioujfjcuiith to (/(i,s iirticlc.

CS3D

Footnotes

f^csearch among the participants ol the Cllobal SuppK C'hain

f-orum shows that successful supply chain management

requires the integration of eight key business proeesses—

both internally and exlernally with key members of the supjily

chain. W h e n that necessary integration is nonexistent or

insuflieient, resources are wasted and supply ehain performance suffers.

26

1 las your company successfully integrated the eross-lunetional business processes descrihed in this article- If the

answer is anything les.s than an unqualified yes, then y{)u re

not creating the most value for your shareholders and vour

sLi[iply ehain partners. The time for aetion is now ,

2 004

^Lambert, Douglas M., and Terrance L, Pohlen. "Supply Chain

Metrics." The International Journal of Logistics Management Vol.

12, 1^0. 1 (2001): pp. 1-19.

^Barry, Leonard L., and A. Parasuraman, "Marketing to Existing

Customers/' Mari<eting Services: Competing Tiirougii Quality.

New York, PJY: The Free Press, 1991, p 11.

^Heskett, James L., W. Earl Sassser, and Leonard A. Schlesinger.

The Service Profit Ciiain, New York, NY: The Free Press, 1997, p.11.

•^Seybold, Patricia B. "Get Inside the Lives of Your Customers."

Harvard Business Reviev\/yo\. 78, No. 5 (2001): pp.1-17.

^Lambert, Douglas M, and Renan Burduroglu. "Measuring and

Selling the Value of Logistics." The International

Journal of

Logistics Management Vol. 11, Mo. 1, (2000): pp. 1-17.