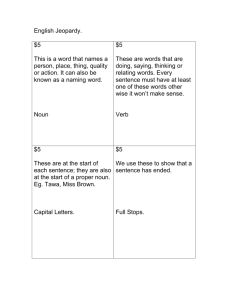

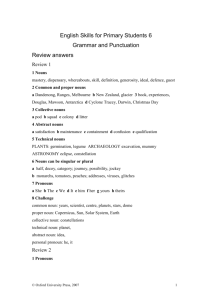

Early Acquisition of Nouns and Verbs Evidence

advertisement