ADEA Smith

advertisement

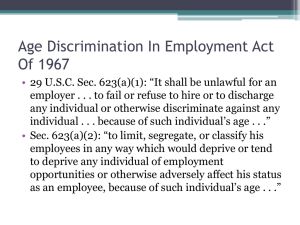

Smith v. City of Jackson, 125 S. Ct. 1536 (2005) In Smith v. City of Jackson, the Supreme Court considered the question left open in its decision in Hazen Paper Co. v. Biggins, and held that disparate impact theory as defined in Griggs v. Duke Power is cognizable under the ADEA. However, a majority of the Court held that the scope of disparate impact theory is narrower under the ADEA than under Title VII, because of the ADEA’s “reasonable factor other than age” language, and because the 1991 Civil Rights Act’s language does not explicitly subsume age discrimination. In 1998, the City of Jackson, Mississippi adopted a pay plan which provided for raises to all City employees, including its police officers. The stated purpose of the plan was to "…attract and retain qualified people, provide incentive for performance, maintain competitiveness with other public sector agencies and ensure equitable compensation to all employees regardless of age, sex, race and/or disability." The plan, as implemented, granted proportionately greater percentage raises to officers with fewer than 5 years of service than the raises granted to those with more seniority – simply because officers who were over 40 years of age generally had more than 5 years of service. The Court unanimously agreed that, although the legislative history of the ADEA discloses distinctions between the institutional arrangements which disadvantage older workers, in contrast to systemic and individual discrimination against workers based on race, sex, color, religion or national origin, the language of the ADEA is otherwise identical to Title VII, except that the ADEA explicitly permits differentiation based on reasonable factors other than age (RFOA). Writing for Justices Ginsburg, Souter and Breyer, Justice Stevens then observed that the Court’s seminal decision in Griggs v. Duke Power had generally interpreted Title VII’s provisions to extend to the consequences of employment practices or mechanisms – thereby allowing workers to challenge such practices or mechanisms without a required showing of discriminatory intent. Justice Stevens noted that, until the Court’s decision in Hazen Paper, most federal appellate courts indeed assumed that Griggs’ disparate impact theory applied in ADEA cases, and that there was no language in the court’s decision in Hazen Paper precluding such an interpretation. Justice Stevens then noted that the ADEA’s “reasonable factors other than age” language does not imply the rejection of disparate impact theory; indeed, he explains, an employer’s reliance on factors other than age defeats the disparate treatment case ab initio, rather than providing for an affirmative avoidance of liability. Disparate impact claims, on the other hand, involve the examination of facially neutral employment practices or policies that disproportionately affect the members of a protected class (emphasis added). In such cases, the “reasonable factors other than age” provision in the ADEA plays a definitive role by allowing the employer to avoid liability if the adverse impact was reasonably attributable to a factor other than age. Justice Stevens concludes that such an interpretation is supported by both the Department of Labor’s original proposal of the statutory language, and the interpretation of the statute by the EEOC. Part IV of the Court’s opinion, however, limits the application of disparate impact theory as announced in the Court’s seminal decision in Griggs. First, while a majority of the Court was willing to recognize disparate impact theory in age cases, the Court’s judgment views the “reasonable factors other than age” language of the statute to suggest that an employee alleging a disparate impact theory of age discrimination must “…isolate and identify the specific employment practices that are allegedly responsible for any observed statistical disparities.” (The employee must point to “a test, requirement or practice” that has an adverse impact on “older” workers). The Court’s limitation on the ADEA’s reach made reference to both Congress’ failure to make clear – as it had done in the 1991 Civil Rights Act – that such limitations of Griggs were inappropriate under Title VII, and the legislative history of the ADEA, which suggested that discrimination against older workers was not as serious – in a social policy sense – as discrimination against workers who needed Title VII’s protections. Applying its interpretation of the ADEA to the instant case, the Court held that the city’s plan was based on factors other than age. Specifically, the plan’s formula for the adjustment of salaries was based on a survey of average pay for police officers in comparable communities in the Southeast. That survey disclosed that the employees most out-of-line with aspirational salary levels were those in the three lowest ranks in Jackson’s police force (regardless of age). The few officers in the two highest ranks (all over 40 years of age) received higher dollar amount raises under the adjustment plan, but because of their higher salaries, their raises represented a smaller percentage of their salary than did the raise awarded to lower rank officers. Plaintiff’s only complaint therefore is that a statistically significant number of officers over 40 years of age received raises lower in percentage relation to their current salary than the percentage raise awarded to younger employees (emphasis added). The plan was not however based on age, but rather sought simply to bring employee salaries into line with regional norms, in order to attract and retain qualified police officers. Viewed in this light, the salary decisions made under the plan were based on reasonable factors other than age. Justice Scalia wrote separately, observing that the Court should simply defer to the EEOC’s interpretation of the ADEA, which would require that “…employment criteria that are age-neutral on their face but which nevertheless have a disparate impact on members of the protected age group must be justified as a business necessity. (Citing United States v. Mead Corp., 533 U.S. 218 (2001). Justice O’Connor dissented, observing that neither the legislative language (including § 4(a)(2) on which the plaintiffs relied), agency interpretation, or the Court’s past decisions suggested any intent by Congress that disparate impact claims are cognizable under the ADEA. Rather it is clear, Justice O’Connor suggests, that the statutory “causation” language in §§ 4(a)(1) and (a)(2), read strictly and in para materiae, clearly restricts its reach to decisions motivated by consideration of age, and not to decisions which merely affect older workers consequently. 2