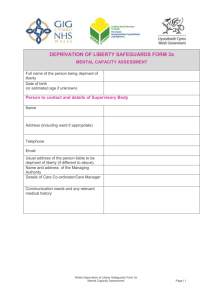

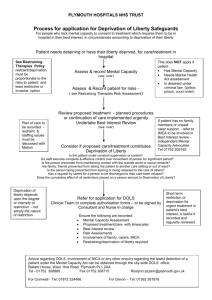

Deprivation of Liberty in the Hospital Setting

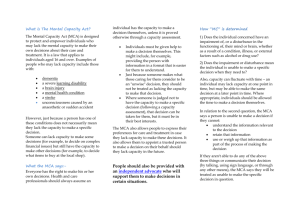

advertisement