The Mental Capacity Act and DoLS Pathway

advertisement

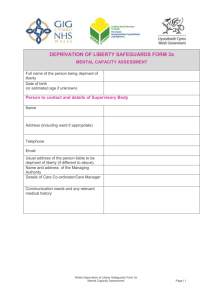

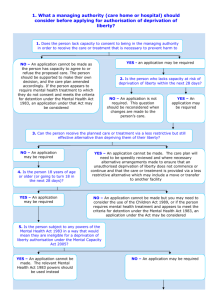

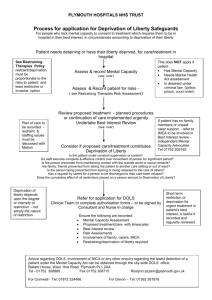

Mental Capacity Act and Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards Mark Crawford - MCA Advisor MCA Team County Hall Mental Capacity Act (underlying principles) • A person (16+) must be assumed to have capacity unless it is proved otherwise. (the law does not allow for judgements based on diagnosis, age, appearance, behaviour) • Everyone should be given all the help and support they need to make a decision, before anyone concludes they cannot make their own decision. • A person is allowed to make what might be seen as an unwise or eccentric decision – this does not in itself indicate a lack of capacity • Any actions or decisions made on behalf of someone who lacks capacity must be in their best interests. • Any actions or decisions should aim to be the least restrictive, in terms of the person’s rights and freedom of action. Requirements of the person assessing capacity No need for qualifications. Knowledge of reasonably foreseeable consequences, risks and benefits of the decision Communication skills Preferably – a knowledge of the person and their history (avoids ‘stranger danger’) How to Determine Capacity In order a person to be unable to make their own decisions they must meet the two stage legal test of capacity. This states that: i) there must be an impairment of, or disturbance in, the functioning of the mind or brain; and ii) this impairment or disturbance must be sufficient that the person lacks the capacity to make that particular decision It is necessary to apply the following test. Can the person: • understand the information relevant to the decision • retain the information long enough to make the decision • use or weigh the information to come to a decision • communicate that decision (in any way recognised by the assessor) It is important to note that each determination of capacity is specific to the particular decision in question and to the particular time at which the decision is made. Best Interest Decision Making The MCA Code of Practice sets out a checklist which every decision maker must use when making decisions on behalf of other people. This emphasises that: •The person’s wishes, feelings, beliefs & values must be taken into consideration •The person must be involved in and participate in the decision as much as they are able to, with appropriate support. •The views of others involved in their care must be considered • All the relevant circumstances must be considered • Judgements must be made in a balanced and nondiscriminatory way, looking at medical, social, emotional, and psychological effects on the person, in relation to the proposed decision • An Independent Mental Capacity Advocate (IMCA) must be involved where the decision involves serious medical treatment, or a change in accommodation, and there are no family or friends to consult • Consideration must also be given as to whether the person might regain capacity and whether the decision could be postponed until then Supreme Court Judgement 19/3/2014 This involved three young people whose Learning Disabilities mean that they require high levels of supervision and control to ensure they receive the care the need One was in a small care home, one was in supported housing and one was in an adult fostering placement The Supreme Court found that all three were deprived of their liberty and Lady Hale’s main judgment gave a clearer definition of what might be a deprivation of someone’s liberty P, or MIG An 18 year old woman with a moderate to severe learning disability and problems with her sight and hearing, who requires assistance crossing the road because she is unaware of danger. She lives with a ‘foster mother’ (commonly called adult placement, or shared lives) whom she regards as ‘mummy.’ Her foster mother provides her with intensive support in most aspects of daily living. She is not on any medication. She has never attempted to leave the home by herself and showed no wish to do so, but if she did, her foster mother would restrain her in her best interests. She attends a further education unit daily during term time and is taken on trips and holidays by her foster mother. A typical situation that might now fall within the expanded definition of deprivation of liberty is that of an older person with dementia, living at home with considerable support. Staff monitor her well-being continuously at home because she forgets to eat, is unsafe in her use of appliances, and leaves the bath taps running; she is accompanied whenever she leaves her home because she forgets where she lives and is at risk of road accidents or abuse from others. She shows no sign of being unhappy or wanting to live elsewhere, but, in her best interests, she would not be allowed to leave to go and live somewhere else even if she wanted to. Supreme Court Judgement - Identifying a Deprivation of Liberty... The Supreme Court’s ‘acid test’ has two key elements: Is the person subject to continuous supervision and control? and Is the person free to leave? It is now clear that if a person lacking capacity to consent to the arrangements is subject both to continuous supervision and control and not free to leave, they are deprived of their liberty. What is no longer relevant? There are now a range of factors that are no longer relevant to identifying a deprivation of liberty (although might still be important when looking at whether the deprivation is in the person’s Best Interests). The factors ruled as irrelevant by the court include: –the person’s compliance or happiness or lack of objection; –the suitability or relative normality of the placement (after comparing the person’s circumstances with another person of similar age and condition); or –the reason or purpose leading to a particular placement though of course all these factors are still relevant to whether or not the situation is in the person’s best interests, and should be authorised. Aim of the Supreme Court To extend the safeguard of independent scrutiny. Lady Hale said: “A gilded cage is still a cage” and that “we should err on the side of caution in deciding what constitutes a deprivation of liberty.” The judges also highlighted that a person in supported living might also be deprived of their liberty. Court of Protection – DoLS Pathway What is: “continuous supervision and control?” “not free to leave?” “lacking the capacity to consent to the placement?” Dorset County Council are developing a pathway to ensure that the necessary cases are taken to the Court of Protection Presumption of Capacity Does Service User have the capacity to consent to their care plan yes no Court Application required no / maybe not undertake a decision specific capacity assessment Does Service User have the capacity to consent to their care plan ? yes no Court application required no no does the existing care plan meet the threshold for deprivation of liberty no no Court application required yes review the Care Plan, can it be amended to be less restrictive no application to the court of protection required yes If the care plan no longer meets the test for deprivation of liberty no court application is required Court of Protection Applications If a deprivation of liberty is identified, the service provider should discuss this with the person’s social worker (or other key professional). This worker will be responsible for initiating the process that will take the case to the Court of Protection Mental Capacity Act and Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards Any Questions?