Intimate Discrimination - University of Toronto Faculty of Law

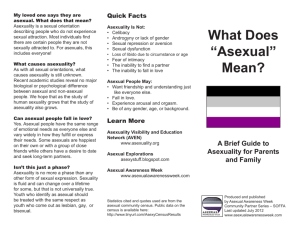

advertisement