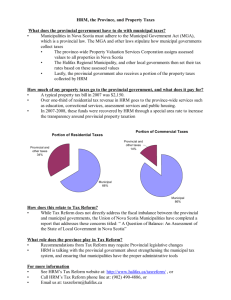

municipal property taxation in nova scotia

advertisement