CHILD LABOR - University of Essex

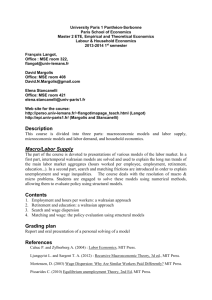

advertisement