SchoolNet: A Case Study of Implementation in Three Schools

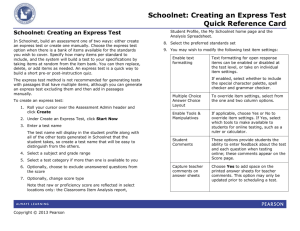

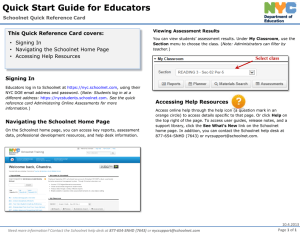

advertisement