Clinical Medicine: Therapeutics

Review

Open Access

Full open access to this and

thousands of other papers at

http://www.la-press.com.

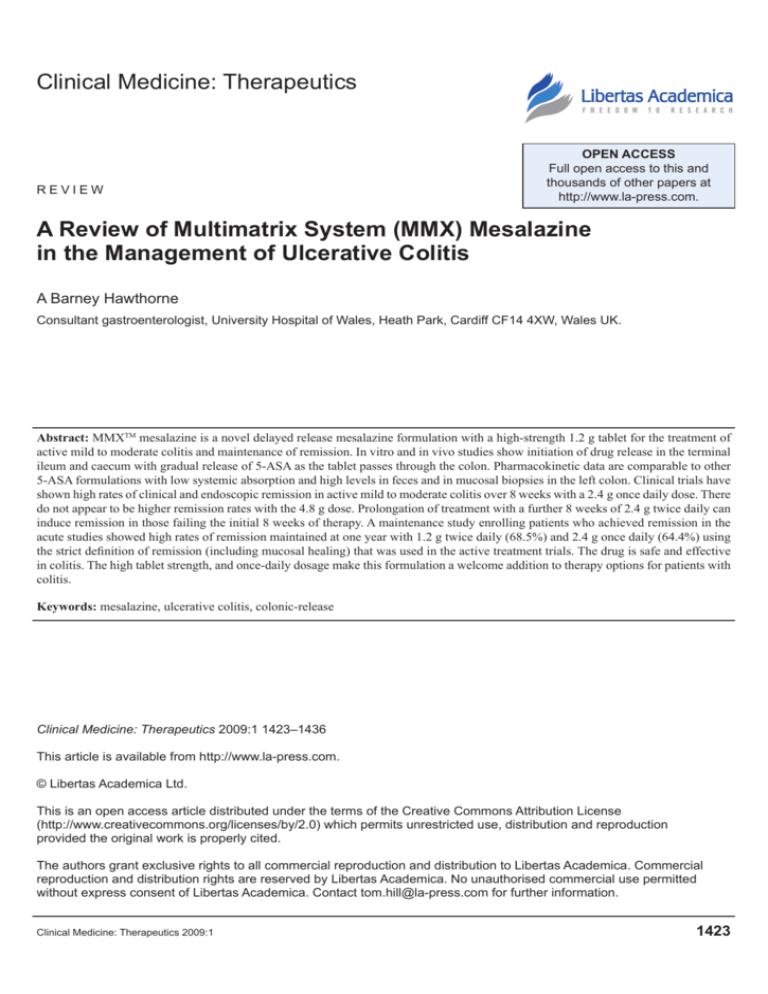

A Review of Multimatrix System (MMX) Mesalazine

in the Management of Ulcerative Colitis

A Barney Hawthorne

Consultant gastroenterologist, University Hospital of Wales, Heath Park, Cardiff CF14 4XW, Wales UK.

Abstract: MMXTM mesalazine is a novel delayed release mesalazine formulation with a high-strength 1.2 g tablet for the treatment of

active mild to moderate colitis and maintenance of remission. In vitro and in vivo studies show initiation of drug release in the terminal

ileum and caecum with gradual release of 5-ASA as the tablet passes through the colon. Pharmacokinetic data are comparable to other

5-ASA formulations with low systemic absorption and high levels in feces and in mucosal biopsies in the left colon. Clinical trials have

shown high rates of clinical and endoscopic remission in active mild to moderate colitis over 8 weeks with a 2.4 g once daily dose. There

do not appear to be higher remission rates with the 4.8 g dose. Prolongation of treatment with a further 8 weeks of 2.4 g twice daily can

induce remission in those failing the initial 8 weeks of therapy. A maintenance study enrolling patients who achieved remission in the

acute studies showed high rates of remission maintained at one year with 1.2 g twice daily (68.5%) and 2.4 g once daily (64.4%) using

the strict definition of remission (including mucosal healing) that was used in the active treatment trials. The drug is safe and effective

in colitis. The high tablet strength, and once-daily dosage make this formulation a welcome addition to therapy options for patients with

colitis.

Keywords: mesalazine, ulcerative colitis, colonic-release

Clinical Medicine: Therapeutics 2009:1 1423–1436

This article is available from http://www.la-press.com.

© Libertas Academica Ltd.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License

(http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0) which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction

provided the original work is properly cited.

The authors grant exclusive rights to all commercial reproduction and distribution to Libertas Academica. Commercial

reproduction and distribution rights are reserved by Libertas Academica. No unauthorised commercial use permitted

without express consent of Libertas Academica. Contact tom.hill@la-press.com for further information.

Clinical Medicine: Therapeutics 2009:1

1423

Hawthorne

Mesalazine or 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA)

remains the first-line therapy for treatment of mild to

moderately active ulcerative colitis, and maintenance

of mucosal healing. The drug exerts a topical antiinflammatory effect on colonic mucosa. Therapeutic

benefit of sulphasalazine was first described in 1942

by Svartz.1 Recently there has been a resurgence of

interest in several aspects of mesalazine use. There

is new information on mechanism of action through

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ)

receptors, effect on carcinogenesis, new technology

in drug delivery coatings to allow gradual release of

the drug after reaching the colon, and higher dose per

tablet, and a growing number of trials showing that once

daily dosing is as effective as divided doses. This review

discusses a new formulation of 5-ASA—multimatrix

(MMX) mesalazine: the evidence for its clinical

effect, pharmacokinetics, and safety in comparison

to other preparations of 5-ASA currently available.

Pharmacology

The clinical efficacy of sulphasalazine in ulcerative

colitis was a serendipitous discovery. The drug

was originally designed as a combination of an

antibacterial agent (sulphapyridine) linked to an antiinflammatory agent (5-ASA) by an azo bond, in order

to treat rheumatoid arthritis, at a time when it was

thought to have an infective as well as inflammatory

aetiology. It is ironic that the initial studies failed

to show the benefits of the drug in rheumatoid

arthritis (that subsequently were shown in larger

studies), but did show benefit in ulcerative colitis

patients in the rheumatoid arthritis trial, confirmed

in randomized controlled trials.2 Later studies in

distal colitis showed that the active agent was 5-ASA

rather than sulphapyridine,3 and that 5-ASA was

as effective as intact sulphasalazine and exerted a

topical effect on the colonic mucosa.4,5 Uncoated

5-ASA is rapidly and completely absorbed in the

proximal small intestine, but poorly absorbed from

the colon.6 It is metabolised to N-acetyl 5-ASA, by

N-acetyl-transferase 1 (NAT 1), present in intestinal

epithelial cells and liver. N-acetyl 5-ASA had no antiinflammatory activity in two of three trials.7–9 As the

sulphapyridine moiety was responsible for most of the

toxicity of sulphasalazine,10,11 it was logical to develop

coated forms of 5-ASA that were released in the colon.12

1424

Colonic release of 5-ASA

The first delayed-release 5-ASA tablet used a

pH-sensitive acrylic resin (Eudragit S) and was

developed and evaluated in Cardiff, and produced as

Asacol®.13 The resin dissolves at pH 7, and utilises

the fact that pH gradually rises through the small

intestine, to achieve pH 7 in the terminal ileum14

(Fig. 1). Since then a range of further coatings have

been developed to deliver drug to the colon using

other pH-sensitive resins (Claversal®, Mesasal®),

delayed-release microgranules using ethylcellulose

(Pentasa®), or alternative non sulfa-containing

prodrugs (balsalazide, olsalazine) (Table 1).

Pharmacokinetics

The pharmacokinetics of mesalazine have been

widely studied,15 but it is clear that plasma levels

do not necessarily reflect drug efficacy for a drug

with a topical effect on colonic mucosa. It is easy

to demonstrate significant variations in plasma

pharmacokinetic profiles, but it is not at all clear that

this correlates with drug efficacy, although there is

a great dearth of adequately powered comparative

studies. Plasma levels may be more important as

an indicator for potential nephrotoxicity. There is

however no evidence that drugs with more proximal

small bowel release and higher plasma levels are any

more toxic, and it seems more likely that interstitial

nephritis is either an idiosyncratic or hypersensitivity

reaction.15 Most of the pharmacokinetic studies

have been performed in healthy volunteers.

There is also evidence to show that patients with

quiescent ulcerative colitis have colonic motility and

8

7.5

7

pH

Introduction

6.5

6

5.5

5

proximal small

intestine

Distal small

intestine

caecum/Rt

colon

Left

colon/rectum

Figure 1. pH gradient along gastrointestinal tract in man.

Clinical Medicine: Therapeutics 2009:1

MMXTM mesalazine in ulcerative colitis

Table 1. Current Oral 5-ASA formulations.

Generic name

Proprietary name

Formulation

Site of release

Strength

Sulfasalazine

Azulfidine Salazopyrin

5-ASA and sulfapyridine

linked by azo-bond.

Tablet

Colon

500 mg

(200 mg 5-ASA)

Sulfasalazine

Azulfidine EN-tabs

Salazopyrin EN-tabs

As above, but tablet

coated with cellulose

acetate phthalate

Colon

500 mg

(200 mg 5-ASA)

Olsalazine

Dipentum®

5-ASA dimer linked

by azo-bond. Gelatin

capsule

Colon

250 mg

Olsalazine

Dipentum®

5-ASA dimer linked by

azo-bond. Tablet

Colon

500 mg

Balsalazide

Colazide®, Colazal®

5-ASA and

4-aminobenzoylβ-alanine (4ABA) linked

by azo-bond. Capsule

Colon

750 mg

(262 mg 5-ASA)

Mesalazine

N American Asacol®*

Eudragit-S coated

tablets (release at

pH 7)

Terminal ileum, colon

400 mg 800 mg

Mesalazine

United Kingdom, Italy,

Netherlands Asacol®*

Eudragit-S coated

tablets (release

at pH 7)

Terminal ileum, colon

400 mg 800 mg

Mesalazine

Ipocol®# Mesren®#

Eudragit-S coated

tablets (release

at pH 7)

Terminal ileum, colon

400 mg

Mesalazine

Salofalk® Mesasal®

Claversal®

Eudragit-L coated

tablets (release at

pH 6). Tablets,

granules

Distal ileum, colon

250 mg tablets 500 mg

and 1 g sachets

Mesalazine

Pentasa®

Ethylcellulose-coated

microgranules (timedependent release)

available as a tablet,

capsule or sachet

Duodenum, jejunum,

ileum, colon

500 mg tablet 1 g

and 2 g sachet

Mesalazine

Mezavant®

Eudragit-S coated tablet

containing inner core of

Multi-Matrix System □

Terminal ileum, colon

1.2 g

*North American Asacol® manufactured by the original Tillotts Laboratories process, whereas changes in manufacturing process of European Asacol® may

result in differences in thickness of coating and excipients. #Differences in manufacturing processes of generic tablets may result in differences in coating

and excipients making the release characteristics different to Asacol®. □ A matrix containing lipophilic and hydrophilic excipients.

function that is similar to healthy controls.16,17 The

pharmacokinetics of mesalazine should therefore

be the same in quiescent ulcerative colitis as in the

normal colon.

Need for novel 5-ASA delivery systems

There are a number of theoretical reasons to

develop novel 5-ASA delivery systems. The

ethylcellulose-coated and Eudragit-L coated

Clinical Medicine: Therapeutics 2009:1

preparations undoubtedly release 5-ASA higher in

the small intestine than Eudragit-S coatings.15 This

should result in higher plasma levels, and thus greater

urinary excretion of 5-ASA. In fact it is difficult to

demonstrate this in the numerous pharmacokinetic

studies, where interindividual variation is far

greater, but there is some evidence of greater total

urine 5-ASA for Claversal®, Salofalk® and Mesasal

compared to all the others.15 Faecal excretion is

1425

Hawthorne

however broadly similar for all preparations. The

only exception to this is the effect of administering

bisacodyl to volunteers to increase colonic transit and

cause diarrhoea.18 This resulted in a marked increase

in faecal excretion of the pro-drugs sulphasalazine

and olsalazine. This was more significant than

the increase in faecal loss of free 5-ASA when the

bisacodyl-treated volunteers were given Asacol® or

the other slow-release preparations. When comparing

UC patients with and without diarrhoea, a similar

increase in faecal loss of unsplit sulfasalazine

and olsalazine is found,19 but the amount of free

5-ASA (as a proportion of total free- and acetylated

5-ASA) rose most dramatically in diarrhoea patients

receiving Asacol® from 66% to 87%. In other words,

very little Asacol® was being acetylated in patients

with diarrhoea, and may link with observations of

patients that they pass intact or partially dissolved

tablets at times. The rise in proportion of free 5-ASA

in faeces was not as marked for Pentasa® or Salofalk®

with diarrhoea.19

An ideal drug delivery system would not release

drug at all in the upper small bowel, but start to

release the drug gradually in the ileocaecal region,

and then progressively throughout the colon. In this

way, unacetylated active drug would be available

through the colon. It is worth noting that the right

colon is generally thought to be a storage and mixing

organ and chyme is likely to travel back and forth

for some time in this area, as water is absorbed and

the consistency of stool gets more solid. Once a mass

action occurs, the stool then passes more rapidly

down the left colon before evacuation. The left colon

in normal patients, and certainly in active colitis, is

generally relatively empty, and represents a much

more challenging area for drug delivery.

Evaluation of intestinal release profiles

It is necessary therefore to evaluate the release

characteristics of these formulations in the gut. There

are two main techniques used to assess the rate of

dissolution of slow-release tablets, and the location in

the gut where this occurs. In vitro, the pH conditions

of the gut can be simulated by measuring the rate of

dissolution of tablet coatings in fluids at different

pHs. Systems have been developed to simulate more

accurately conditions in the normal gut, including

pH, body temperature, peristalsis, gut secretions,

1426

nutrient and water absorption and colonic microbiota.

An example is the TNO GastroIntestinal Model (TIM;

TNO Quality of Life, Zeist, The Netherlands).20 There

are of course limitations to these models as they cannot

completely simulate an organ whose function is still

so poorly understood. It is also clear from in vivo

magnetic resonance imaging of intestinal fluid along

the gut, that there are fluid pockets, separated by areas

of collapsed gut containing only minimal amounts of

secretions.21

The second, in vivo method,22 involves labelling

tablets with radioactive tracer (152Sm2O3) added

during tablet manufacture and then neutron-irradiated

to produce 153Sm2O3. Gamma scintigraphy can then

follow the dissolution of individual tablets after

oral ingestion, with measurement of radioactivity

in regions of interest plotted out on the basis of

typical anatomy (stomach, small intestine, ileocaecal,

ascending, transverse, descending colon and rectum).

The limitations of this technique are the complexity of

the incorporation of tracer into tablets, the possibility

that this may alter the release characteristics of

5-ASA, and the possibility that tracer release may

not accurately correspond to drug release. Variable

anatomy may also limit the accuracy of plotting

regions of interest in the gut.

MMXTM multimatrix system

Mesalazine with MMXTM multimatrix system

(MezavantTM, also known as Mezavant XLTM in the

UK and Ireland, and LialdaTM in the USA: Shire

Pharmaceuticals Inc, Wayne PA, USA, under licence

from Giuliani SpA, Milan, Italy) is a novel tablet

coating designed to release mesalazine gradually

throughout the colon. The outer coating is a gastroresistant Eudragit-S film that dissolves above pH 7

(usually in the terminal ileum). Within this is a core

of lipophilic and hydrophilic matrix. Once exposed to

intestinal fluid, this absorbs water to form a sponge-like

viscous gel mass, containing the drug. The lipophilic

elements creates a partially hydrophobic environment

in the core, and is expected to slow the penetration of

aqueous fluid into the tablet, and allowing the slow

diffusion out of the drug as it passes round the colon,

allowing contact of the drug with a larger surface

area of mucosa before conversion to n-acetyl 5-ASA.

The hydrophilic elements may promote adherence

to colonic mucosa. This proposed mechanism is

Clinical Medicine: Therapeutics 2009:1

MMXTM mesalazine in ulcerative colitis

thought to have the advantage of gradual 5-ASA

release through the colon. This review will discuss

the evidence that this occurs, and the clinical benefit

in relation to other preparations.

In vitro, dissolution of MMXTM mesalazine has been

studied in the TIM-1 and TIM-2 system (simulating

stomach and small intestine, and colorectum

respectively).23 In simulated fasting and fed conditions,

less than 1% of drug is released in stomach and small

intestine during a mean residence time of 5 hours

(fasted) and 6 hours (fed). Release of 78% (69%–87%)

occurred in the colon in the simulated fasting state

(over a mean 19 hours), but was 68% (61%–76%) in

the fed state (mean 18 hours residence). No sign of the

tablet was left in the colon residue. This model cannot

indicate what level in the colon the drug is released,

but measuring 5-ASA release in the colon dialysate

over time indicates a sigmoidal pattern, (slow rising

initially and then after a 2–3 hour lag, increasing

linearly to a peak of release at 6–8 hours (fasted) and

5–6 hours (fed). There are no comparative studies

with other 5-ASA preparations, but the results do

suggest that MMXTM release is gradual once the colon

is reached, in this in vitro model.

The in vivo release of MMXTM mesalazine has

been studied using gamma-scintigraphy. Brunner et al

studied 12 healthy volunteers using 153Sm2O3 labelled

tablets, and plasma pharmacokinetics.24 In fasting

single-dose studies, the mean gastric emptying time

was 0.4 ± 0.4 hours (hr), with appearance in the small

intestine at 0.8 ± 0.5 hr, ileum at 4 ± 1 hr and colon

at 5.8 ± 1.2 hr. Initial tablet disintegration started

at a mean of 6.9 ± 1.1 hr, in ascending (n = 8) or

transverse colon (n = 4). It was difficult to determine

time to complete dissolution, as there was a tail of

radioactivity behind the tablet on scintigraphic images.

Plasma levels peaked (Tmax) when tablets were in the

ileocaecal region. Plasma levels as area under curve

(AUC) were 12.37 nmol/ml, comparable to that of

other slow-release 5-ASA preparations and prodrugs.15 19.9 ± 18.2% of drug absorption occurred in

the ileal region, and 80.1 ± 18.2% in the colon. Urinary

excretion was measured for 24 hours, with a mean 9%

of administered dose excreted (almost all acetylated).

This is less than in studies with other drugs, with mean

values ranging from 11%–33% for sulfasalazine,

Asacol® 10%–35%, Pentasa® 15%–53%, and up

to 27%–56% for Salofalk®, Mesasal and Claversal®.15

Clinical Medicine: Therapeutics 2009:1

It should be noted however that the elimination process

was not complete at 24 hours (plasma concentrations

still significant at this point, and in some subjects,

the start of the decay phase had still not occurred).

Overall, the results suggest a low systemic availability

of 5-ASA with the MMXTM mesalazine tablet, and a

slower and more sustained release from the ileocaecal

region onwards through the colon.

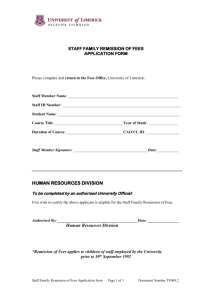

A small study has used the same scintigraphic

method to compare release of MMXTM mesalazine

and delayed-release mesalazine (Asacol® Giuliani,

S.p.A., Milan, Italy) in eight healthy volunteers in

a single-dose, two-way, cross-over design.25 Plasma

release of both tablets was very similar, with a

Tmax at approximately eight hours. Scintigraphy

showed initial disintegration slightly earlier for

MMXTM mesalazine (4.75 ± 1.3 hours) than Asacol®

(6.16 ± 1.8 hours). Complete disintegration was later

however for MMXTM mesalazine (17.4 ± 8.6 hours)

versus Asacol® (7.3 ± 2.1 hours). The location of

complete disintegration was also more distal for

MMXTM mesalazine (Fig. 2). These scintigraphic

studies demonstrate the variability in location of

tablet disintegration between individuals. Whether this

variability is greater between different preparations

is not clear.

In summary, both in vitro and in vivo studies

confirm that initial disintegration of MMXTM

mesalazine is in the ileocaecal region but subsequent

release is gradual through the colon.

Clinical trials of MMXTM mesalazine

(Table 2)

A small preliminary trial was carried out in five Italian

centres to evaluate the effect of MMXTM mesalazine

in active left-sided disease compared to 5-ASA

enemas.26 Patients had disease extending more than

15 cm but no further than splenic flexure and had

mild to moderate disease activity as determined by

a clinical disease activity (Rachmilewitz score) 6.27

This was an eight week double-blind double-dummy

trial comparing MMXTM mesalazine 1.2 g three times

daily plus placebo enema (n = 40) with Asacol®

4 g/100 ml enema with placebo tablets. The primary

end-point was remission at eight weeks, defined

by a Rachmilewitz score of 4. In the MMXTM

group, 60% achieved remission, versus 50% in the

enema group. This study showed that oral MMXTM

1427

Hawthorne

A

MMX mesalazine

Asacol

5

4

3

2

Dc

sF

Tc

HF

Ac

IcJ

DsB

MsB

0

psB

1

s

number of subjects

6

Region of gut

Active disease

B

MMX mesalazine

Asacol

5

4

3

2

Dc

sF

Tc

HF

Ac

IcJ

DsB

MsB

psB

1

s

number of subjects

6

0

Figure 2. Scintigraphic location of initial dissolution (Fig. 1a) and

Region of gut

complete tablet dissolution (Fig. 1b) for MMXTM mesalazine or Asacol®

tablets radiolabelled with 153Sm2O3 in 8 healthy volunteers given a single

tablet.36

Abbreviations: S, stomach; PSB, proximal small bowel; MSB, mid small

bowel; DSB, distal small bowel; ICJ, ileocaecal junction; AC, ascending

colon; HF, hepatic flexure; TC, transverse colon; SF, splenic flexure;

DC, descending colon.

mesalazine is as effective as enemas in left-sided

disease, confirming delivery of drug in significant

amounts to the left colon. A small dose-ranging pilot

study28 investigated the efficacy of three different

doses (1.2 g, 2.4 g and 4.8 g given once daily to

13, 14 and 11 patients respectively) in patients with

mild to moderate active UC (UC-DAI score 4–10)29

1428

extending beyond the rectum. The primary end-point

was remission at eight weeks as defined by a UC-DAI

score 1, with a zero score for rectal bleeding and

stool frequency and at least a one-point reduction

in sigmoidoscopy score from baseline. No patients

in the 1.2 g group achieved remission, versus

4 (30.8%) in the 2.4 g group and 2 (18.2%) in the

4.8 g group. There was however a dose-response

relationship in improvement in UC-DAI score, and

also in rectal and sigmoidoscopic histology scores.

Levels of 5-ASA and acetyl-5-ASA in colonic

mucosa were considerably higher in the 4.8 g group

(48.8 ng/mg and 29.7 ng/mg) compared to the 1.2 g

group (11.2 ng/mg and 6 ng/mg) and the 2.4 g group

(6.9 ng/mg and 7 ng/mg).

A large phase III double-blind parallel-group study

in 280 patients compared 1.2 g twice daily, versus

4.8 g daily versus placebo over eight weeks in mild to

moderate active UC.30 The trial used a modification of

the Sutherland UC-disease activity index (UC-DAI).

The index has a maximum score of 12 comprising

a score of 0–3 each for rectal bleeding, increased

stool frequency, sigmoidoscopic appearance and

physicians global assessment. The sigmoidoscopic

score was modified. In Sutherland’s sigmoidoscopic

score, normal scores 0, erythema, decreased vascular

pattern, or mild friability scores 1, and marked friability

scores 2, with ulceration and spontaneous bleeding

scoring 3. This was modified to make any degree

of friability give a score of 2. This has the effect of

making the score somewhat more objective, reducing

interobserver variability and indeed bringing it in

line with the original sigmoidoscopic score devised

by Baron.31 Mild to moderate disease was defined as

a score of 4–10, with the sigmoidoscopic score of

0 or more, and the physician’s global assessment as

2 or less. The relapse duration had to be less than six

weeks, and patients were excluded if they had relapsed

using more than 2 g mesalazine. The primary endpoint was clinical and endoscopic remission at eight

weeks (i.e. modified UC-DAI score 1, with a score

of 0 for rectal bleeding and stool frequency, and no

mucosal friability and at least a 1-point reduction in

sigmoidoscopy score. Using this stringent definition,

12.9% on placebo achieved remission, with 34.1%

in the 1.2 g twice daily, and 29.2% in the 4.8 g daily

Clinical Medicine: Therapeutics 2009:1

MMXTM mesalazine in ulcerative colitis

Table 2. Trials of MMXTM mesalazine in active UC and maintenance of remission.

Trial

Study population

Treatment arm

Number

treated

Primary end-point

Result

Significance

compared

to placebo

Prantera26

Mild-moderate

active left-sided

colitis

1.2 g three

times daily

40

60%

n/a

Asacol®

4 g/100 ml

enema

39

Remission at 8 wks

(Rachmilewitz CAI

score 4)

50%

n/a

Mild-moderate

active colitis

(proctitis excluded)

1.2 g daily

13

0%

n/a

2.4 g daily

14

30.8%

n/a

4.8 g daily

11

Remission at 8 weeks

(UC-DAI score 1

with score 0 for rectal

bleeding and stool

frequency and at

least 1-point reduction

from baseline

sigmoidoscopy score

18.2%

n/a

Mild-moderate

active colitis

(proctitis excluded)

Placebo

88

12.9%

1.2 g twice

daily

88

4.8 g daily

89

Remission at 8 weeks

(modified UC-DAI

score 1, with score

0 for rectal bleeding

and stool frequency,

no mucosal friability

and at least a 1-point

reduction from baseline

sigmoidoscopy score

Placebo

86

2.4 g daily

84

D’Haens28

Lichtenstein

et al30

Kamm

et al32

Kamm

et al33

Mild-moderate

active colitis

(proctitis excluded)

UC in remission

(proctitis excluded)

4.8 g daily

85

Asacol®

800 mg tid

86

1.2 g twice

a day

234

2.4 g daily

225

group (Table 2). There was no significant difference

between the doses.

A similar trial32 ran concurrently with this study,

and had the same entry criteria, definitions and endpoints. Patients were randomized to 2.4 g once daily,

4.8 g once daily, placebo, or a comparator group

of Asacol® 800 mg three times daily, all for eight

weeks. The latter tablets were over-capsulated with

a gelatine capsule to ensure blinding. The study was

not powered to detect a difference between MMXTM

mesalazine and Asacol®. In spite of such similar

Clinical Medicine: Therapeutics 2009:1

34.1%

P 0.001

29.2%

P 0.009

22.1%

“

Safety and tolerability

over 12 months

(Remission as defined

above for Lichtenstein

et al was secondary

end-point)

40.5%

P = 0.01

41.2%

P = 0.007

32.6%

P = 0.124

Remission at

12 mo 68.5%

n/a

Remission at

12 mo 64.4%

n/a

design, the rates of clinical and endoscopic remission

was higher than in the previous study at 22.1% in the

placebo group, rising to 40.5% in the 2.4 g group, and

41.2% in the 4.8 g daily group. The remission rate

in the Asacol® comparator group was 32.6%, which

was not statistically significant compared to placebo.

There were no significant safety concerns with either

of these studies, and together they show convincingly

that MMXTM mesalazine is an effective treatment for

mild or moderate colitis in a once daily dosage of

2.4 g, with no benefit from increasing to 4.8 g daily.

1429

Hawthorne

Maintenance of remission

A one year maintenance trial followed on for patients

in the above two trials of active colitis. This trial was

designed to assess safety and tolerability of MMXTM

mesalazine.33 For those achieving remission at the

end of the active treatment period, they could enrol

directly (n = 246), and for others they could receive

a further 8 weeks of 2.4 g MMXTM mesalazine twice

daily (312 patients, of whom 213 achieved remission

and were enrolled). These numbers included

approximately 20% who had not achieved the strict

definition of remission required in the index trials, but

were deemed well enough by the investigators to enter

the maintenance phase. Patients were re-randomized

to either 2.4 g daily, or 1.2 g twice a day. At one year,

there were 64.4% of patients in remission (using the

strict definition above) in the 2.4 g daily group, versus

68.5% in the 1.2 g twice a day group. When defined as

the absence of a relapse requiring additional treatment,

88.9% (once daily) and 93.2% (twice daily) remained

in remission. The differences between groups were

not significant. These results show high numbers

remaining in remission, (in comparison to other

maintenance studies), but it is worth remembering

that this is a selected population, who had not relapsed

previously on more than 2 g mesalazine, and who had

responded well in the active treatment trial.

Dose-response with 5-ASA

in Active Disease

To date, the evidence for dose-response in treatment

of colitis remains contentious. In theory, a higher dose

of 5-ASA might be more effective by saturating the

acetylating enzyme capacity in colonic mucosa, thus

increasing availability of the active free 5-ASA.34

The trials of MMXTM mesalazine to date do not

show an advantage of 4.8 g daily over 2.4 g in active

disease. This is in keeping with most of the literature

on 5-ASA. In the trial comparing 1.6 g Asacol® with

4.8 g, Schroeder et al35 found the higher dose more

effective. Sutherland, however, in his Cochrane

review meta-analysis,36 concluded that 1.6 g was

insufficient, and at least 2 g was needed, but it was not

possible to demonstrate a dose-response above this

level. In the Ascend I and II trials37,38 of 2.4 g versus

4.8 Asacol® over six weeks in mild to moderate colitis,

there was significant benefit of the higher dose only

evident in the moderate group (72% improvement

1430

with 4.8 g versus 59% with 2.4 g in Ascend II),

with no significant benefit in the mild colitis group.

In the Ascend III study,39 in spite of including

772 patients with moderately active disease, there

was a numerical increase from 66% improvement

with 2.4 g to 70% on 4.8 g. This benefit is of dubious

clinical significance. The MMXTM mesalazine studies

were not powered to demonstrate differences in the

dose regimens. A pooled analysis of the two large

active treatment trials do not show overall benefit

for the 4.8 g dose over 2.4 g.40 Three hundred and

four patients who did not achieve remission in the

two eight week MMXTM mesalazine studies,30,32

were given open-label MMXTM mesalazine 2.4 g

twice daily for a further eight weeks, as reported in

the maintenance study.33 Of these, 59.5% achieved

remission according to the stringent definition

used in the trials. When patients were separated

according to the initial treatment group they had

been in, there was no difference in remission rates:

the placebo group had 57% remission, 2.4 g MMXTM

mesalazine 61.5%, 4.8 g MMXTM mesalazine 60.3%

and the Asacol® 2.4 g group 61% remission after

the eight week extension. The implication is that it

is the prolongation of treatment, rather than the switch

to high dose, that achieved remission. In conclusion,

there is no evidence that doses of MMXTM mesalazine

above 2.4 g daily have greater efficacy.

Safety and Tolerability

In the literature, 5-ASA is recognised as an

extremely safe drug, with headaches and nausea

being the commonest side-effects. In the trials of

MMXTM mesalazine to date, no significant safety

concerns have arisen. In the D’Haens28 study,

headache was the commonest adverse event,

occurring in 21% of patients. This was also reported

in the other trials,26,28,30,32,33 but no more commonly

in the active treatment than in the placebo groups,

and there was no evidence of a dose response—i.e.

no increase in frequency in the high-dose or once

daily dose groups. Overall, gastrointestinal sideeffects were the commonest, again no more

common than in the placebo group. Two cases of

pancreatitis occurred (one on 2.4 g and one on 4.8 g

daily), a documented side-effect of 5-ASA.41 Both

resolved on withdrawal of medication. One patient

developed a hepatitis, but a subsequent infectious

Clinical Medicine: Therapeutics 2009:1

MMXTM mesalazine in ulcerative colitis

mononucleosis test was positive, and glandular

fever the likely cause.

No renal failure or interstitial nephritis was

recorded in the 723 patients in the MMXTM mesalazine

trials to date. Interstitial nephritis is recognised as

a complication of mesalazine treatment and exact

frequency is unknown. Renal impairment (elevated

creatinine) was found in 0.2% in a large study involving

2940 patients.42 In one study of 223 IBD patients,43

microalbuminuria was found in up to a third of patients

treated with doses of more than 3 g daily, and appeared

to be dose-dependent. A UK review of reports to

the Committee on Safety in Medicines (CSM) from

1991–8 (2.8 million prescriptions for mesalazine,

4.7million for sulfasalazine) found 11.1 reports per

million prescriptions for mesalazine, but none for

sulfasalazine.44 Even considering the incomplete

nature of adverse event notifications through this

system, the disparity implies that the higher plasma

levels seen with delayed-release 5-ASA15 are relevant

in causing renal damage, although they are still at least

10-fold lower than salicylate levels in patients taking

aspirin. Other renal complications of untreated IBD

include tubular proteinuria, renal calculi, amyloidosis

and glomerulonephritis, and it has been proposed

that interstitial nephritis could also be related to

the underlying IBD (more severe disease likely to

require higher doses of 5-ASA). However, it is well

recognised that early withdrawal of 5-ASA results

in resolution of the renal function, providing strong

evidence that this is a drug-related hypersensitivity.

If mesalazine-induced interstitial nephritis is not

recognised, then permanent renal impairment is

likely to result.45 In conclusion, renal toxicity from

5-ASA does occur, but is rare, and as yet there is no

strong evidence that it is dose-dependent. There is no

evidence of differences in risk, either with different

5-ASA colonic-release mechanism, nor with oncedaily therapy.

There is evidence that 5-ASA inhibits thiopurine

methyltransferase in vitro, and so could potentially

affect metabolite levels of azathioprine and

6-mercaptopurine.46 In theory higher levels could

have a more pronounced effect, with more thioguanine

nucleotides, responsible for marrow suppression.

A study comparing 2 g with 4 g doses of mesalazine

for 4 weeks however showed no significant

difference in thioguanine nucleotide levels, although

Clinical Medicine: Therapeutics 2009:1

6 methylmercaptopurine levels were significantly

lower on the high dose.47 High-dose mesalazine could

in theory enhance the effectiveness, and also toxicity

of coprescribed thiopurines, but in reality this effect

is likely to be non-clinically significant.

Once Daily Therapy with 5-ASA

In the past it was assumed that divided dosing

would maximise the time that drug would spend in

contact with colonic mucosa and this would improve

efficacy, but this has never been shown to be true.

With a growing interest in treatment adherence, once

daily therapy is an important consideration, if it could

be shown to be as safe and as effective as divided

doses. A study in Sheffield of steady state plasma

pharmacokinetics (after 7 days) showed that in

normal subjects, median peak concentrations, trough

concentrations, and areas under the curve were similar

for once-daily and three-times-daily mesalazine

dosing regimens using Asacol®.48 Urine and fecal

5-ASA 24 hour collections were also similar, as were

levels in rectal biopsies. This implies that safety is

not a concern, (albeit with a maximum daily dose

of only 2.4 g). The study was not able to measure

peak levels in the colonic lumen, which might have

therapeutic relevance. A computer simulation model

of 5-ASA levels in segments of the colon predicts

that both total and regional levels would be similar

after once daily, and three times daily dosing with

Asacol®.49 The same model did predict that levels

in sigmoid colon and rectum would be considerably

lower than in the right colon with Asacol®, and this

difference would be exacerbated by frequent bowel

actions, as in active colitis.

A pilot feasibility study of once daily (Asacol®,

using 400 mg tablets) versus conventional dosing

of mesalazine for the maintenance of remission of

ulcerative colitis, was the first study to investigate

once daily dosing.50 Over six months, there was one

relapse in the 12 patients on daily dosing (average

2.5 g daily) versus one relapse among the 10 patients

taking an average 2.7 g per day either in twice daily

or three times daily administration (Table 3). The

authors concluded that a larger trial was warranted.

Four of the MMXTM mesalazine trials to date have

included once daily arms,28,30,32,33 and have confirmed

that once daily dosing is as effective as divided doses,

both in active disease and maintenance of remission.

1431

Hawthorne

Table 3. Trials of once-daily 5-ASA therapy (MMXTM mesalazine trials shown in Table 2).

Trial

Study population

Treatment arm

Number Primary

treated end-point

Result

Kane et al50

UC in remission

Asacol® once daily

in usual dose

(mean 2.5 g daily)

12

1/12 (8%) n/a

relapse

Asacol® in usual

twice or three

times daily dosing

(mean daily

dose 2.7 g)

10

1/10

(10%)

relapse

Salofalk® granules

3 g once daily

191

Remission

79%

Non-inferiority

(CAI 4 at

remission confirmed

week 8 (last

observation

carried forward))

Salofalk® granules

1 g three times

daily

189

Pentasa® granules

2 g once daily

169

Pentasa® granules

1 g twice daily

184

Kruis et al51

Dignass et al53

Active UC (excluding

proctitis) with clinical

activity index 4 and

endoscopic index 4

(Rachmilewitz) REF

UC in remission based

on UC-DAI score 2

(excluding proctitis)

The 1.2 g MMXTM tablet has made it easier to dose

once daily with a small number of tablets. These

studies were powered to compare each dose regimen

with placebo, and were not designed to demonstrate

non-inferiority of once daily compared to divided

doses.

Two further studies have now been completed using

5-ASA granules that were designed as non-inferiority

studies. Eudragit-L coated 5-ASA (Salofalk®) in the

form of granules was investigated in active UC by

Kruis et al51 in a single-blind study. Of 381 patients

enrolled, 347 completed the study, which used

the Rachmilewitz CAI index27 4 as the primary

end-point. 79% patients treated with 3 g once daily

achieved remission, compared to 75.7% in the 1 g t.i.d.

arm. The confidence interval for the difference was

3.4% [95% confidence interval (CI) -5.0%–11.8%].

Using the same end-point as in the MMXTM mesalazine

trials (modified DAI score 1 with score 0 for rectal

bleeding and stool frequency and at least 1-point

reduction from baseline sigmoidoscopy score),30 the

1432

n/a (pilot study)

Significance

75.7%

remission

Remission

rate at 1 yr

(UC-DAI 2)

analysed by

Kaplan-Meier

method

70.9%

Once daily

remission superior

(p = 0.024)

58.9%

remission

once daily group achieved 37% remission, versus

39% in the t.i.d. group. These figures are virtually the

same as the two MMXTM mesalazine active colitis

trials.32,33 The Kruis trial results also showed that in

patients treated with once daily 3 g, those with distal

disease had statistically better outcomes than those

with more extensive disease, and also did better

than those with distal disease treated with 1 g t.i.d.

This was an exploratory analysis, and is most likely

to have arisen by chance, but the authors speculated

that the difference could be explained by once daily

therapy giving intermittent high 5-ASA levels in the

distal colon.

A pharmacokinetic study in 30 healthy volunteers

had shown bioequivalence for once versus twice

daily administered 4 g of ethylcellulose-coated

5-ASA.52 In the Podium trial,53 the investigators

evaluated the clinical effectiveness of a granule

preparation of Pentasa® for maintenance of remission

in a single-blind non-inferiority designed study. The

study used the UC-DAI score,29 and patients enrolled

Clinical Medicine: Therapeutics 2009:1

MMXTM mesalazine in ulcerative colitis

had to have a score of 2, with proctitis patients

excluded. Patients taking 2 g Pentasa® granules once

daily (n = 169) did better with 70.9% remaining in

remission at 1 year, than the 184 patients taking

1 g bd. Although designed as a non-inferiority study,

the outcome was in fact statistically superior for the

2 g daily dose (p = 0.024). Using Cox regression

analysis, the difference related to the improved

adherence in the once daily dosing group. An

economic analysis showed that once daily treatment

was cost-saving in this trial, mainly due to reduced

relapse rate.54

Adherence

In the controlled environment of clinical trials, with

a high level of medical supervision, approximately

70%–95% of IBD patients adhere to their

medication.55,56 However, this high rate of medication

adherence is not reflected in normal clinical practice.

A cross sectional study of US outpatients with quiescent

UC found that only 40% were adherent to maintenance

mesalazine therapy.56 Several community-based

studies have reported non-adherence rates ranging

from 43% to 72% of IBD patients.57 In the UK,

approximately 15% of patients fail to even redeem

prescriptions at the pharmacist.58 Treatment nonadherence rates vary considerably between countries

(in Europe, a survey of 203 IBD patients revealed

self-reported non-adherence rates ranging from 13%

to 46%).59 The implications are extensive, with good

evidence of higher relapse rates in non-adherent

patients,60 and evidence that non-continuation of

long-term 5-ASA increases colorectal cancer risk.61

Non-adherence is likely to result in a significant

increase in treatment costs.62 Poor adherence is

strongly linked to complex dosage regimens.63 In a

study involving 105 hypertensive patients receiving

long-term treatment, once daily (od) or twice daily (bd)

dosing was associated with significant improvements

in mean adherence rates compared with 3-times daily

(tds) dosing,64 and many other reviews confirm that

od and bd dosing is associated with better adherence

than more frequent dosing.64 It is more difficult to

show the small benefit increment from switching

from bd to od dosing.65

It is evident that non-adherence during maintenance

therapy for quiescent disease is far more likely than

in active disease. In the Podium trial of maintenance

Clinical Medicine: Therapeutics 2009:1

once daily therapy with Pentasa® granules,53

adherence was recorded by medication returns.

This was higher for the once daily (versus twice

daily) group, but not statistically significant. In a

validated questionnaire, patients in the twice daily

group reported higher rates of forgetting medication,

or carelessness about their medication. Visual

analogue scores showed significantly improved

acceptability for once daily. In a multivariate

analysis, treatment adherence was a significant

factor in improving outcome over one year, whereas

the dosing regimen was no longer significant. In the

Salofalk® granule study of once daily versus three

times daily therapy in active UC,51 adherence was

not specifically assessed, but on questioning, 82%

of patients preferred once daily dosing, compared

to only 2% preferring three times daily. In the

MMXTM mesalazine acute studies evaluating once

daily therapy,30,32 the studies were double-blind

and double-dummy, so the once daily groups were

still taking multiple daily tablets and differences

in adherence were not noted. In the maintenance

MMXTM mesalazine trial33 which was open-label,

there was no difference in treatment adherence

(recorded on pill counts as adherent if 80% of

medication taken), with 93.3% adherence in the

once-daily group and 99.6% in the twice-daily

group. In summary, adherence is greatly improved

when dosage can be given once or twice daily, but

the difference between once and twice daily is not

significant. It is likely that patient preference may

be the most important factor, and the freedom to

take medication once or twice daily is an advantage,

and may be a factor in quality of life.

Quality of Life

In ulcerative colitis, disease symptoms are the

main determinant of quality of life (QOL) at any

one time.66 In an eight week trial comparing 1 g,

2 g and 4 g Pentasa® or placebo in active UC,

quality of life was evaluated in 374 patients, and

was significantly improved compared to placebo

in the 2 g and 4 g dose groups.67 The benefit was

seen in all 12 QOL parameters, including five

disease-specific parameters (e.g. trips to the toilet or

urgency) and seven general QOL parameters (e.g.

ability to sleep, sexual relationships, or hobbies/

recreations). Effective medication is thus a vital

1433

Hawthorne

tool in improving QOL. In a qualitative study of

IBD patient experiences,68 over two thirds identified

medication as necessary in controlling symptoms,

in spite of being a nuisance, a concern regarding

toxicity, and anti-drug feelings. Two-thirds of the

patients also reported a desire to self-manage their

medication. In the Podium study,53 health-related

utility was measured, and was strongly linked to

disease severity,69 and although not different between

once-daily and divided dose groups, the option of

once-daily dosing is likely to lead to higher quality

of life if relapse rates are lower.

Conclusions

MMXTM mesalazine is a novel 5-ASA delivery tablet

that starts to release the drug in the terminal ileum

and caecum, and then allows the slow release of drug

during passage through the colon. The theoretical

advantages of this formulation are borne out in the

clinical trial data. In mild and moderate colitis these

show high rates of remission and mucosal healing in

clinical trials with stringent end-points. Once daily

dosing is as effective as divided doses, and the 2.4 g

dose appears as effective as 4.8 g daily. Although

the clinical trials included Asacol® as a comparator,

there are no adequately powered non-inferiority or

superiority trials to show that MMXTM mesalazine

is more effective than other 5-ASA preparations, but

the drug has the advantage of a high strength 1.2 g

tablet and well-designed trials showing high clinical

and endoscopic remission rates in active disease

and maintenance of remission with once-daily

therapy. It is becoming clear that once daily therapy

is effective for other formulations of 5-ASA, and

this benefit is not exclusive to MMXTM mesalazine.

Other considerations, particularly cost and patient

preference, must be taken into consideration in

choosing a formulation for individual patients, but there

is no doubt that this drug is a welcome addition to the

therapeutic armamentarium.

Disclosure

Dr Hawthorne has received honoraria and participated

in continuing medical educational events supported

by Shire Pharmaceuticals Inc, Proctor and Gamble,

Ferring Pharmaceuticals, and Dr Falk Pharma,

and received research funding from Proctor and

Gamble.

1434

References

1. Svartz N. Salazopyrin, a new sulfanilamide preparation: A. Therapeutic

results in rheumatic polyarthritis: B. Therapeutic results in ulcerative

colitis: C. Toxic manifestations in treatments with sulfanilamide preparation.

Acta Medica Scandinavia. 1942;110:557–90.

2. Baron JH, Connell AM, Lennard-Jones JE, et al. Sulphasalazine and

salicylazosulphadimidine in ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 1962;I:1094–6.

3. Azad Khan AK, Piris J, Truolove SC. An experiment to determine the active

therapeutic moiety of sulphasalazine. Lancet. 1977;II:892–5.

4. Van Hees PA, Bakker JH, van Tongeren JH. Effect of sulphapyridine,

5-aminosalicylic acid, and placebo in patients with idiopathic proctitis:

a study to determine the active therapeutic moiety of sulphasalazine. Gut.

1980;21:632–5.

5. Klotz U, Maier K, Fischer C, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of sulfasalazine and

its metabolites in patients with ulcerative colitis and Cron’s disease. N Engl

J Med. 1980;303:1499–502.

6. Schroder H, Campbell DE. Absorption, metabolism, and excretion of

salicylazosulfapyridine in man. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1972;13:539–51.

7. Willoughby CP, Piris J, Truelove SC. The effect of topical N-acetyl

5-aminosalicylic acid in ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol.

1980;15:715–9.

8. Binder VS, Halskov E, Hvidberg E, et al. A controlled study of

5-acetaminosalicylic acid (5-Ac-ASA) as enema in ulcerative colitis.

Scand J Gastroenterol. 1981;16:1122.

9. Van Hogezand RA, van Hees PA, van Gorp JP, et al. Double-blind

comparison of 5-aminosalicylic acid and acetyl-5-aminosalicylic acid

suppositories in patients with idiopathic proctitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther.

1988;2:33–40.

10. Das KM, Eastwood MA, McManus JP, Sircus W. Adverse reactions during

salicylazosulfapyridine therapy and the relation with drug metabolism and

acetylator phenotype. N Engl J Med. 1973;289:491–5.

11. Taffet SL, Das KM. Sulfasalazine. Adverse effects and desensitization.

Dig Dis Sci. 1983;28:833–42.

12. Dew MJ, Hughes PJ, Lee MG, Evans BK, Rhodes J. An oral preparation

to release drugs in the human colon. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1983;16:

738–40.

13. Dew MJ, Hughes P, Harries AD, Williams G, Evans BK, Rhodes J.

Maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis with oral preparation of

5-aminosalicylic acid. Br Med J. 1982;285:1012.

14. Nugent SG, Kumar D, Rampton DR, Evans DF. Intestinal luminal pH in

inflammatory bowel disease: possible determinants and implications for

therapy with aminosalicylates and other drugs. Gut. 2001;48:571.

15. Sandborn WJ, Hanauer SB. Systematic review: the pharmacokinetic

profiles of oral mesalazine formulations and mesalazine pro-drugs

used in the management of ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther.

2003;17:29–42.

16. Rao SS, Read NW, Brown C, Bruce C, Holdsworth CD. Studies on the

mechanism of bowel disturbance in ulcerative colitis. Gastoenterol.

1987;93:934–40.

17. Rao SS, Read NW. Gastrointestinal motility in patients with ulcerative

colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1990;172:22–8.

18. Rijk MC, van Hogezand RA, van Schaik A, van Tongeren JH. Disposition

of 5-aminosalicylic acid from 5-aminosalicylic acid-delivering drugs during

accelerated intestinal transit in healthy volunteers. Scand J Gastroenterol.

1989;24:1179–85.

19. Rijk MCM, van Schaik A, van Tongeren HM. Disposition of mesalazine

from mesalazine-delivering drugs in patients with inflammatory bowel

disease, with and without diarrhoea. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;27:

863–8.

20. Minekus M, Smeets-Peeters M, Bernalier A, et al. A computer-controlled

system to simulate conditions of the large intestine with peristaltic mixing,

water absorption and absorption of fermentation products. Appl Microbiol

Biotechnol. 1999;53:108–14.

21. Schiller C, Frohlich CP, Giessmann T, et al. Intestinal fluid volumes and

transit of dosage forms as assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. Aliment

Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:971–9.

Clinical Medicine: Therapeutics 2009:1

MMXTM mesalazine in ulcerative colitis

22. Davis SS, Hardy JG, Newman SP, Wilding IR. Gamma scintigraphy in

the evaluation of pharmaceutical dosage forms. Eur J Nucl Med. 1992;

19:971–86.

23. Tenjarla S, Romasanta V, Zeijdner E, Villa R, Moro L. Release of

5-aminosalicylate from an MMXTM mesalamine tablet during transit

through a simulated gastrointestinal tract system. Advances in therapy.

2007;24:826–40.

24. Brunner M, Assandr R, Kletter K, et al. Gastrointestinal transit and 5-ASA

release from a new mesalazine extended release formulation. Aliment

Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:395–402.

25. Wray H, Joseph RE, Palmen M, Pierce D. A pharmacokinetic and

scintigraphic comparison of MMXTM mesalamine and delayed-release

mesalamine. Poster presented at the American College of Gastroenterology

Meeting, Orlando, Fl, USA 3–8 Oct 2008.

26. Prantera C, Viscido A, Biancone L, Francavilla A, Giglio L, Campieri M.

A new oral delivery system for 5-ASA: preliminary clinical findings for

MMx. Infl Bowel dis. 2005;11:421–7.

27. Rachmilewitz D. Coated mesalazine (5-aminosalicylic acid) versus

sulphasalazine in the treatment of active ulcerative colitis: a randomised

trial. Br Med J. 1989;298:82–6.

28. D’Haens G, Hommes D, Engels L, et al. Once daily MMXTM mesalazine

for the treatment of mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis: a phase II,

dose-ranging study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1087–97.

29. Sutherland LR, Martin F, Greer S, et al. 5-aminosalicylic acid enema in

the treatment of distal ulcerative colitis, proctosigmoiditis, and proctitis.

Gastroenterol. 1987;92:1894–8.

30. Lichtenstein GR, Kamm MA, Boddu P, et al. Effect of once- or twicedaily MMXTM mesalamine (SPD476) for the induction of remission of

mild to moderately active ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.

2007;5:95–102.

31. Baron H, et al. Variation between observers in describing mucosal

appearances in proctocolitis. BMJ. 1964;1:89–92.

32. Kamm MA, Sandborn WJ, Gassull M, et al. Once-daily, high-concentration

MMXTM mesalamine in active ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterol.

2007;132:66–75.

33. Kamm MA, Lichtenstein GR, Sandborn WJ, et al. Randomised trial of

once- or twice-daily MMX™ mesalazine for maintenance of remission in

ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2008;57:893–902.

34. De Vos M, Verdievel H, Schoonjans R, et al. Concentrations of 5-ASA and

Ac-5-ASA in human ileocolonic biopsy homogenates after oral 5-ASA

preparations. Gut. 1992;33:1338–42.

35. Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic

acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized

study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1625–9.

36. Sutherland L, Macdonald JK. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for induction

of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:

CD000543.

37. Hanauer S, Sandborn W, Kornbluth A, et al. Delayed-release oral

mesalamine at 4.8 g/day (800 mg tablet) for the treatment of moderately

active ulcerative colitis: the ASCEND II trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:

2478–85.

38. Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ, Dallaire C, et al. Delayed-release oral

mesalamine 4.8 g/day (800 mg tablets) compared to 2.4 g/day (400 mg

tablets) for the treatment of mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis:

The ASCEND I trial. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21:827–34.

39. Sandborn WJ, et al. DDW2008. GE. 2008;134 S1:A99.

40. Sandborn WJ, Kamm MA, Lichtenstein GR, Lynes A, Butler T, Joseph RE.

MMXTM Multi Matrix System mesalazine for the induction of remission in

patients with mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis: a combined analysis of two

randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Aliment Pharmacol

Ther. 2007;26:205–15.

41. Bergholm U, Langman M, Rawlins M, et al. Drug-induced acute pancreatitis.

Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Safety. 1995;4:329–34.

42. Hanauer SB, Verst-Brasch C, Regalli G. Renal safety of long-term

mesalamine therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol.

1997;112(suppl)A991.

Clinical Medicine: Therapeutics 2009:1

43. Schreiber S, Hamling J, Zehnter E, et al. Renal tubular dysfunction in

patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with aminosalicylate. Gut.

1997;40:761–6.

44. Ransford RAJ, Langman MJS. Sulphasalazine and mesalazine: serious

adverse reactions reevaluated on the basis of suspected adverse reaction

reports to the Committee on Safety of Medicines. Gut. 2002;51:

536–9.

45. Tadic M, Grgurevic I, Scukanec-Spoljar M, et al. Acute interstitial nephritis

due to mesalazine. Nephrology. 2005;10:103–5.

46. Gilissen LDL, Bierau J, Derijks LJJ, et al. The pharmacokinetic effect

of discontinuation of mesalazine on mercaptopurine metabolite levels

in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;

22:605.

47. Graaf PD, de Boer N, Jharap B, Mulder CJ, van Bodegraven AA, Schwab M.

Alteration of Thiopurinephosphate Metabolite Levels By Aminosalicylates

in IBD-Patients. Gastroenterol. 2008;134(suppl 1):A69.

48. Hussain FN, Ajjan RA, Kapur K, Moustafa M, Riley SA. Once versus

divided daily dosing with delayed-release mesalazine: a study of tissue

drug concentrations and standard pharmacokinetic parameters. Aliment

Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:53–62.

49. Thorpe MP, Ehrenpreis ED, Putt KS, Hannon B. A dynamic model of

colonic concentrations of delayed-release 5-aminosalicylic acid (Asacol).

Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:1193–201.

50. Kane S, Huo D, Magnanti K. A pilot feasibility study of once daily versus

conventional dosing mesalamine for maintenance of ulcerative colitis.

Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;1:170–3.

51. Kruis W, Kiudelis G, Racz I, et al. Once-daily versus three-timesdaily mesalazine granules in active ulcerative colitis: a double-dummy,

randomised non-inferiority trial. Gut. 2008: epub.

52. Gandia P, Idier I, Houin G. Is once-daily mesalazine equivalent to the

currently used twice daily regimen? A study performed in 30 healthy

volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;47:334–42.

53. Dignass AU, Bokemeyer B, Adamek H, et al. Mesalamine once daily is

more effective than twice daily in patients with quiescent ulcerative colitis.

Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009. In press.

54. Connolly M, Nielsen SK, Currie CJ, Poole CD, Travis SPL. Once daily

mesalazine for maintaining remission is cost-saving compared to twice

daily mesalazine: an economic evaluation based on the Podium randomised

controlled trial. Gut. 2008;57(suppl II):A261.

55. Kane SV, Cohen RD, Aikens JE, Hanauer SB. Prevalence of non-adherence

with maintenance mesalamine in quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am J

Gastroenterol. 2001;96(10):2929–33.

56. Kane SV. Systematic review: adherence issues in the treatment of ulcerative

colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:577–85.

57. Rubin G, Hungin AP, Chinn D, et al. Long-term aminosalicylate therapy

is under-used in patients with ulcerative colitis: a cross-sectional survey.

Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16(11):1889–93.

58. Beardon PH, McGilchrist MM, McKendrick AD, et al. Primary

non-compliance with prescribed medication in primary care. BMJ.

1993;307(6908):846–8.

59. Robinson A. Patient-reported compliance with 5-ASA drugs in inflammatory

bowel disease: a multi-national study. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(4):

A-499.

60. Kane S, Huo D, Aikens J, et al. Medication non-adherence and outcomes of

patients with quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am J Med. 2003;114:39–43.

61. Moody GA, Jayanthi V, Probert CS, et al. Long-term therapy with

sulphasalazine protects against colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis:

a retrospective study of colorectal cancer risk and compliance with treatment

in Leicestershire. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8(12):1179–83.

62. Review article: medication non-adherence in ulcerative colitis—

strategies to improve adherence with mesalazine and other maintenance

therapies. Hawthorne AB, Rubin G, Ghosh S. Aliment Pharmacol Ther.

2008;27:1157–66.

63. Claxton AJ, Cramer J, Pierce C. A systematic review of the associations

between dose regimens and medication compliance. Clin Therapeutics.

2001;23(8):1296–310.

1435

Hawthorne

64. Eisen SA, Miller DK, Woodward RS, et al. The effect of prescribed

daily dose frequency on patient medication compliance. Arch Int Med.

1990;150:1881–4.

65. Greenberg RN. Overview of patient compliance with medication dosing:

a literature review. Clin Ther. 1984;6(5):592–9.

66. Han, et al. Inflamm Bowel. Dis. 2005;11:24–34.

67. Robinson M, Hanauer S, Hoop R, Zbrozek A, Wilkinson C. Mesalamine

capsules enhance the quality of life for patients with ulcerative colitis.

Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1994;8:27–34.

68. Hall NJ, Rubin GP, Dougall A, Hungin APS, Neely J. The fight for

‘health-related normality’: a qualitative study of the experiences of

individuals living with established inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

J Health Psychology. 2005;10:443–55.

69. Poole CD, Nielsen SK, Currie CJ, Marteau P. Quality of life (health-related

utility) in adults with ulcerative colitis in remission vs. mild/moderate

and severe relapse: findings from the Podium study. Gut. 2008;

57(suppl II):A260.

Publish with Libertas Academica and

every scientist working in your field can

read your article

“I would like to say that this is the most author-friendly

editing process I have experienced in over 150

publications. Thank you most sincerely.”

“The communication between your staff and me has

been terrific. Whenever progress is made with the

manuscript, I receive notice. Quite honestly, I’ve

never had such complete communication with a

journal.”

“LA is different, and hopefully represents a kind of

scientific publication machinery that removes the

hurdles from free flow of scientific thought.”

Your paper will be:

•

Available to your entire community

free of charge

•

Fairly and quickly peer reviewed

•

Yours! You retain copyright

http://www.la-press.com

1436

Clinical Medicine: Therapeutics 2009:1