A nutrition knowledge test for nutrition educators

advertisement

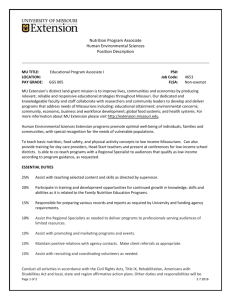

A Nutrition Knowledge Test for Nutrition Educators Carol Byrd-Bredbenner College oj Human Development, The Pennsylvania State University University Park, Pennsylvania 16802 This paper describes the development of a criterion-referenced instrument for assessing nutrition knowledge of potential nutrition educators. The test consists of 50 multiple-choice items. It addresses 3 content areas- basic nutrition principles, sources of nutrients, and function of nutrients; and it measures 4 cognitive levels -recall, comprehension, application, and analysis. The results of an administration of the test to 576 college graduates demonstrate that the instrument discriminates between groups of professionals who are trained in nutrition and those who are not. (JNE 13:97-99, 1981) ABSTRACT With the current interest in nutrition education programs, many individuals with a variety of backgrounds have undertaken or have been assigned the task of teaching nutrition (1-3). Since many view these individuals as experts, they may influence others to a great extent, even though they may have little or no formal nutrition training (4-6). An evaluation instrument which measures nutrition knowledge of potential nutrition educators could serve to select qualified nutrition educators, to identify those who need more training in nutrition, and to maintain quality nutrition education programs. This paper describes the development and validation of such an instrument. TEST DEVELOPMENT The plan for development of this instrument followed the rules of test construction offered by Gronlund (7) and by Ahmann and Glock (8). Similar to those described by Eppright et al. (9), 3 broad nutrition concepts-basic nutrition principles, sources of nutrients, and functions of nutrientsserved as the framework for the test. A panel of 6 nutrition experts reviewed and approved these concepts as important to understanding the application of nutrition. This panel also reviewed objectives that had been written for each concept. They selected 13 objectives judged to reflect basic, rather than advanced, nutrition knowledge. This panel of nutrition experts also addressed the issue of the relative importance of the concepts and objectives. They decided that the concept of basic nutrition principles was most important and would be addressed by half of the items in the test. They perceived the concepts of nutrient VOLUME 13 NUMBER 3 1981 sources and of nutrient functions to be less important but of approximately equal importance relative to each other. The nutrition experts also reviewed and revised for accuracy 94 multiple-choice items that had been constructed to measure knowledge of the concepts and objectives. A panel of 7 experts in educational measurement evaluated the construction of items and categorized the revised items according to the first 4 cognitive levels-recall, comprehension, application, and analysis-of Bloom's taxonomy (10). The test items corresponded to a ninth-grade reading level according to the readability scale constructed by Fry (11). Thus, reading difficulty would not compromise the performance by the intended, college-educated users of the test. A group of 20 graduate students and staff in nutrition and home economics education completed a pilot test of the 94 items. Items answered incorrectly by more than 30010 of this group were eliminated on the basis that the question was poorly constructed, misleading, or more advanced than could be considered basic nutrition. To make up the final 50-item test instrument, test items that met the difficulty index criterion of 0.7 or greater and were in the comprehension, application, or analysis category were selected preferentially to ensure that this instrument would measure nutrition knowledge at levels higher than the recall level. The high difficulty index, i.e., one that required items to be quite easy, reflected the design of this test as a criterionreferenced or mastery test. The participants of the pilot test, nutrition and home economics graduate students and staff, should have mastered the basic nutrition knowl- edge that every individual responsible for nutrition education should possess. Recall items meeting the difficulty index criterion were added after inclusion of all higher level items. Appropriate representation of the nutrition concepts also received consideration in the item selection process. A group of 35 college students from a variety of majors completed a pilot test of the final 50-item instrument. This testing provided data for further item analysis, for determination of internal consistency, and for revision. The mean score for the college students was 38.5, with the range from 20 to 50. The reliability was 0.86, as calculated by the Kuder-Richardson 20 (K-R 20) formula (7,8). The major refinement resulting from this pilot test was identification and revision of nonfunctioning distractors. Table 1 displays the final distribution of test items according to nutrition concepts and cognitive levels. The table of specifications that guided item construction and selection throughout the process required that 4 cognitive levels be represented and that basic nutrition principles receive more emphasis than sources of nutrients or functions of nutrients. Content validity of the final test instrument is ensured because the table of specifications reflects expert opinion in nutrition and in measurement. VALIDATION DESIGN The purpose of this validation study was to determine whether the test instrument would distinguish groups of professionals with nutrition training from groups without nutrition training and to examine reliability of the instrument. The 77,556 graduates from Pennsylvania State University between 1968 and 1978 served as the population from which the test validation sample was drawn. This population included 346 nutritionists, 448 home economists, 1,240 nurses, 1,207 health and physical educators, and 773 elementary educators. Examination of college records established that graduates of nutrition majors were required to take several nutrition courses and that some formal nutrition coursework also was JOURNAL OF NUTRITION EDUCATION 97 required for graduation in home economics, nursing,and health and physical education. No formal requirement for coursework in nutrition existed for graduation in elementary education or for a bachelor's degree in general. A random selection of 300 individuals from each group plus 300 additional persons from the remaining 73,542 graduates of other majors comprised the sample. These subjects received a survey form containing a request for demographic information, the 50-item test instrument, and instructions for completion and return of the survey. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. One to 10 years had elapsed since these graduates had received their baccalaureate degrees. This length of time allowed for variations in age, postbaccalaureate study, pursuit of professional activities, and other such demographic characteristics so that this sample could be considered generally representative of professionals in their respective fields of study. RESULTS Overall, of the 1,800 subjects surveyed, 576 (32070) returned completed test instruments. The response rate varied among groups; respondents included 45% of the nutritionists, 31 % of the home economists, 35% of the nurses, 26% of the health and physical educators, 26% of the elementary educators, and 29% of the graduates in other majors. The possibility exists that respondents could represent a biased sample of each group. Return of the survey was voluntary, and rtc> comparable nutrition knowledge data are available for nonrespondents. However, analysis of the age, race, and sex distribution of respondents revealed no significant differences from the distribution of these characteristics of the entire population. Therefore, the nutrition knowledge of the respondents is likely to reflect the level of nutrition knowledge of each professional group. The assumption that elementary educators and college graduates in general would be groups with little nutrition training proved to be correct; 83% and 82%, respectively, of elementary educators and college graduates in general reported no formal coursework in nutrition. The 576 tests underwent item analysis to determine the degree of difficulty of individual items for the 6 groups of respondentsnutritionists, home economists, nurses, health and physical educators, elementary educators, and other college graduates. Overall, 28 of the 50 test items had a rela- 98 JOURNAL OF NUTRITION EDUCATION Table 1 Distribution of items in the final test according to nutrition concepts and cognitive levels Concepts Cognitive Levels" Recall Comprehension 3 6 3 12 12 6 8 26 Basic nutrition principlesb Sources of nutrientsC Functions of nutrientsd Totals Application Totals Analysis 7 2 3 0 25 14 0 9 0 3 11 50 aDescribed by Bloom et al. (Ref. 10) bItems addressed the topics of 4 food groups (3 items), nutrient density (3 items), energy (4 items), weight control (3 items), food preparation (2 items), and nutrient needs (10 items). cItems addressed the topics of bread and cereal (3 items), dairy products (3 items), protein foods (4 items), fruits and vegetables (3 items), and energy (1 item). dltems addressed the topics of general functions (6 items) and specific functions (5 items). Table 2 Internal consistency (Kuder-Richardson 20) of the total test and subtests by group Subtests Group (n) Nutritionists (134) Home economists (93) Nurses (l05) Health and physical educators (77) College graduates, general (88) Elementary educators (79) Total respondents (576) Total Test Basic Nutrition Principles (25 Items) Sources oj Nutrients (14/tems) Functions oj Nutrients (11 Items) 0.468 0.602 0.603 0.598 0.629 0.600 0.694 0.435 0.349 0.256 0.319 0.231 0.286 0.542 0.391 0.480 0.397 tively high difficulty index (0.80 to 1.(0), indicating that 80% or more of all respondents correctly answered these 28 items. Among nutritionists 41 items had a high difficulty index; in contrast, only 20 of the 50 test items received correct responses from over 80% of elementary educators. Thus, consistent with the objective of a criterion-referenced or mastery test, more test items were easier for persons trained in the subject, e.g., nutritionists, than for per sons without such training, e.g., elementary educators. Table 2 presents the K-R 20 internal consistency coefficients for the total test and for the 3 subtests associated with the 3 nutrition concepts addressed by the test. The K-R 20 provides a conservative estimate of reliability for an untimed, single administration of a single form of a test (8). The overall K-R 20 for the total test for the entire sample of 576 was 0.816. Reliabilities for various professional groups were between 0.639 and 0.738. High reliability coefficients are associated with tests that contain a wide range of item difficulty and high item discrimination indices. Since this test contained a pre- (50 Items} 0.639 0.729 0.677 0.722 0.738 0.675 0.816 0.510 0.520 0.424 0.577 ponderance of easy items, one would not expect exceptionally high reliability coefficients. The subtest reliability coefficients for specific groups of respondents were quite low in many cases, especially the subtests with a small number of items. However, the overall reliabilities of the subtests calculated from the entire sample of 576 respondents were reasonable, considering the high difficulty indices. These subtests could be used to identify specific areas of poor nutrition preparation among potential nutrition educators. Table 3 presents the mean score on the nutrition knowledge test for each group of professionals. One-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's method (12) served to assess the significance of differences between means. Nutritionists achieved significantly higher mean scores on the nutrition knowledge test than all other groups; home economists scored significantly higher than did all other groups except nutritionists; and nurses, health and physical educators, and college graduates in general all scored significantly higher on the nutrition knowledge tests than did elementary educators. In VOLUME 13 NUMBER 3 1981 Table 3 Nutrition knowledge scores of groups Scoret Group (n) Mean±SD Nutritionists (134) Home economists (93) Nurses (105) Health and physical educators (77) College graduates, general (88) Elementary educators (79) Total (576) 44.1 ± 3.4a 4O.9±4.6b 37.1 ±4.6c 35.7 ± 5.2c 35.6± 5.4c 33.0± 5.0<1 38.4±6.0 tScores followed by different letters are significantly different (p > 0.05), as determined by ANOVA. general, group comparisons of subtest scores followed the same pattern: nutritionists scored highest, home economists and nurses scored better than the remaining groups, and elementary educators had the lowest mean scores on subtests. These results demonstrate the concurrent validity of the test and that the test functions as a criterion-referenced or mastery test. The professionals with the most nutrition training as undergraduates presented a higher level of mastery than did those with fewer or no such formal courses in nutrition. This test may therefore serve as a tool for determining the mastery or understanding of nutrition subject matter of those persons responsible for or expected to teach nutrition. D NOTE These data were taken in part from the doctoral thesis of Carol Byrd-Bredbenner entitled "The Interrelationships of Nutrition Knowledge, Attitudes Toward Nutrition, Dietary Behavior, and Commitment to the Concern for Nutrition Education," The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania, 1980. A single copy of the test may be obtained from Carol Byrd-Bredbenner, 202 Human Development Building, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania 16802. LITERATURE CITED 1 Kohrs, M. B., J. Nordstrom, R. O'Neal, D. Eklund, B. K. Paulsen, and A. Hertzler. Nutritional status of main food preparers and nutrition education assistants. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 72:282-88, 1978. 2 Petersen, C., and C. Keis. Nutrition knowledge and attitudes of early elementary teachers. Journal of Nutrition Education 4:11-15c, 1972. 3 Brittin, H. Nutrition education for elemen- ENERGY Energy expenditure changes with age, body composition, gender, activity, and extremes of heat and cold, but presumably not significantly within moderate changes in comfortable environmental temperature. M. J. D~uncey (British Journal of Nutrition 45:257-67, 1981) challenged this presumption by measuring energy expenditure of 9 women confined, under carefully controlled and standardized conditions, in a calorimeter for 30 hours at 22°C (72°F) H. E. Sours et al. (American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 34:453-61, 1981) report an investigation by the Center for Disease Control and the Food and Drug Administration of 58 cases of sudden death among obese persons undergoing rapid weight reduction with very low energy regimens. The investigators excluded 14 cases because of incomplete information and 27 cases because of coexistence of clinical disease, mainly atherosclerosis or diabetes; in the remaining 17 cases, the sudden death apVOLUME 13 NUMBER 3 1981 na/8:531-65,1971. EXPENDITURE and 28°C (82°F). The lower temperature was cool but did not cause shivering, and the higher temperature was warm but caused sweating only infrequently for a short duration. Despite the relatively small difference in environmental temperature, average energy expenditure was over 100 kcal greater per 24 hours in the cooler chamber. Evaporative heat loss decreased at the lower temperature, but sensible heat loss increased to a greater extent for a net FATAL tary education majors. Journal of Nutrition Education 3:73, 1971. 4 Godshall, G. A. Nutrition in the elementary school. New York: Harper & Brothers Pubs., 1958, pp. 39-82. 5 LaChance, P. Nutrition education. Journal of Nutrition Education 3:52-53, 1971. 6 Schwartz, N. E. Nutrition knowledge, attitudes, and practices of Canadian public health nurses. Journal of Nutrition Education 8:25-28, 1976. 7 Gronlund, N. E. Measurement and evaluation in teaching. New York: Macmillan Co., 1968, pp. 79-131 and 249-278. 8 Ahmann, J. S., andM. D. Glock. Evaluating pupil growth. 5th ed. Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 1975, pp. 149-257. 9 Eppright, E., H. M. Fox, B. A. Fryer, G. H. Lamkin, and V. M. Vivian. The North Central regional study of diets of pre-school children. 2. Nutrition knowledge and attitudes of mothers. Journal ofHome Economics 62:327-32, 1970. 10 Bloom, B. S., M. D. Englehart, E. J. Furst, W. H. Hill, and D. R. Krathwohl. Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification ' of educational goals. Handbook 1: Cognitive domain. New York: David McKay Co., 1956, pp. 10-59 and 89-200. 11 Fry, E. B. Readability graph: Clarifications, validity, and extension to level 17 . Journal of Reading 21:242-52,1978 12 Games, P. A. Multiple comparisons on means. American Education Research Jour- RAPID WEIGHT positive increase in the cooler chamber. Differences in metabolic rate disappeared during mild exercise but remained fairly constant at about 70/0 higher in the cooler chamber during sleeping, sitting, standing, and after meals. The author suggests that small differences in environmental temperature, even in moderate climates, may influence energy balance to a greater extent than S.M. O. previously believed. LOSS peared related to the weight-loss regimen. Prior to sudden death due to heart arrhythmias, these patients (16 women and 1 man; aged from 23 to 51 years) lost 1.4 to 3.2 kg per week for 2 to 8 months. Energy intake during weight loss was 300 to 400 kcal per day, mainly from "liquid protein" products, supplemented with multivitamins and some minerals and, in 11 cases, with potassium. Ten patients neither smoked nor took nonnutrient medications; 12 were under some degree of medical supervision. The most frequent pathological finding was atrophy of the heart. The authors recognized the inability to conclude a cause-and-effect relationship between the low energy, protein-based weight-loss regimen and death because of the uncontrolled nature of the investigation. Nonetheless, they offer evidence that questions the safety of rapid weight loss using liquid protein diets, even when supplemented with vitamins and potassium and conducted under medical supervision. S.M 0 JOURNAL OF NUTRITION EDUCATION 99