Position Paper: The Pragmatist Use of Diagrams to Theorize

advertisement

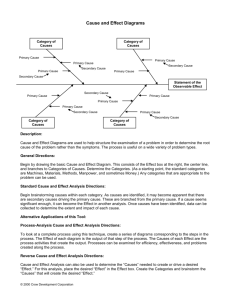

1 Please do not cite or reproduce without permission from the author Position Paper: The Pragmatist Use of Diagrams to Theorize: Charles Peirce and Beyond by Richard Swedberg Cornell University June 23, 2015 Abstract There has been little use of visual representations in sociology, as compared to the natural sciences. While the visualization of data is on the agenda for sociologists today, thanks to big data, this article raises the question if it may not also be possible to visualize theory. So far sociologists have mainly developed so-called theory pictures (Lynch), when they have tried to visualize theory, that is, visual representations that do not go beyond what is said in the text. While these can be useful in some circumstances, it is suggested that it may also be possible to use visual representations in the form of heuristic diagrams that help the researcher to think in a different way, and so come up with new theories or improve existing ones. Especially the ideas of Charles Peirce are very helpful in developing this type of diagrams. A few examples of what these may look like in sociology are presented. It is also noted that the most important diagrams are those that can be used for theorizing in empirical research, rather than the ones that are reproduced in articles and books. For: “Pragmatism and Sociology”, Chicago, August 21, 2015 2 It is much more common to use various forms of visual representations in the natural sciences than in sociology, both when it comes to working out the analysis and when it is being presented.1 As a result, what may be called the visual culture of sociology has been poorly developed (e.g. Fyfe and Law 1984, Edling 2004, Healey and Moody 2014). The drawbacks of this situation have become especially felt with the emergence of big data, where the need for visual representations is extra strong. That different techniques for how to visualize data in social science will develop very quickly seems clear from the fact that big data is here to stay. And presumably this is true both for the kind of visual representations that are needed to explore the data more efficiently, and for those that are needed to display it. So far, however, nothing has been said about the need to visualize theory in sociology, while it is common in the natural sciences to use visual representations to develop and to invent theoretical solutions to scientific puzzles. In this position paper I will discuss what is meant by the visualization of theory in sociology. I will comment on the existing literature on this topic, and suggest a few ways in which to proceed when you visualize theory and use it as a tool in empirical research. I will center the discussion around two different ways of visualizing theory, so-called theory pictures and diagrams with which to theorize. # 1. Theory Pictures Before 1991, when Michael Lynch published a major article on the topic, there existed next to no discussion of the ways in which sociological theory can be visualized (Lynch 1991a; see also Toth 1980, Slawski 1989, Lynch and Wolgar 1990, Turner 2010). Lynch’s general message, however, was a negative one. Most visual representations of theory in sociological work, he found, were of poor quality and primitive in nature. They rarely went beyond what was said in the text. 1 This position paper is based on the full paper, which has also been sent to the organizers of the conference and may be available on the webpage of the conference. 3 Lynch distinguishes between several different types of visual representations in sociology. These are all well known to most sociologists. You can, for example, link factors through causal or quasi-causal vectors, as in organizational charts and ecological models. In another common figure, theory is represented by fourfold or multifold conceptual squares. Wellknown examples of this can be found in the works of Parsons, Luhmann and Habermas. Different versions of path-analytical diagrams are common as well. Finally, according to Lynch, there also exist various schemes, primarily developed by anthropologists, which are used to represent such topics as calendars and kinship networks. Lynch’s term for all of these visual representations is theory picture. A theory picture, he suggests, is typically constructed and used to convey an impression of rationality and scientific rigor. The main point to convey to the reader through theory pictures is that the analysis is truly scientific. The visual representations, as he phrases it, are a form of “rationalized mathematics” (Lynch 1991a:11). There is also another quality to the existing figures in sociology that Lynch is very critical of. This is that “they do not supply readers with puzzles, evidences, or notation systems from which to work out a sense of what the text is saying independent of its words” (Lynch 1991a:11). Theory pictures simply repeat what is said in the text and do not use the full capacity of visual representations. In my view – and in contrast to Lynch - theory pictures are often valuable. This is especially the case when they exhibit the following three qualities: clarity, economy and expressiveness. A combination of these can make an illustration very useful as a way of summarizing a theoretical argument. It can also make it easier to memorize a theory and to teach it. I will return later to the importantance of teaching students the technique of visualizing theory. # 2. Diagrams for Theorizing While theory pictures do fill a useful role, they are not very useful for generating new theoretical ideas. For this, I suggest we need what I will call diagrams for theorizing or heuristic diagrams for theorizing in sociology. While a theory picture allows you to get a quick and efficient view of some existing theory, a theorizing diagram is a tool for theorizing. A theory picture is also closed by nature, in the sense that it represents a finished theory. In contrast, a 4 theorizing diagram is open, meaning by this that it does not have a single solution but can be worked out in many different ways. There exists a fairly huge literature on diagrams in general, from classical texts by James Clerk Maxwell and Charles Sanders Peirce, to a quickly growing modern literature, with contributions by anthropologists, cultural historians, cognitive scientists, logicians and many others (e.g. Maxwell 1877; Peirce 1906; Larkin and Simon 1987; Cheng and Simon 1995; Glasgow, Narayanan and Chandrraskaran 1995; Osborn 2005; Nersessian 2008:161-66; Bender and Marrinan 2010; Cromley et al 2010; Gooding 2010; Kirsh 2010; Eddy 2014; Shin, Lemon and Mumma 2014). One of the many insights from this literature is that diagrams draw on the human capacity to understand and reason in a multi-modal way, that is, not only with the help of words and numbers, but also through visual representations of various types. Whether there exists a distinct type of “diagrammatic reasoning” or not, it is clear that people can think effectively in other ways than with the help of formal logic, and that they also do so. Another insight that has come out of the modern literature is that a line can be drawn between outer representations, of the type that can be found on a page or a computer screen, and inner representations, which refer to what goes on inside the mind. In a simplified formulation you can say that people either think with the help of outer representations, according to the theory of outer representations, or they are thought to be biologically programmed to think in inner representations. One way to work with a heuristic or theorizing diagram is the following. You first focus on the diagram for a few minutes till you have made the transition into its visual language. Once you are “inside” the diagram, you think in its images and follow its logic, that is, you think in a different way than when you exclusively use words. You should then begin to play around with the parts that make up the diagram, conducting as it were mental experiments in order to tease out new aspects of the problem it addresses. While some people are known to think primarily in terms of images (Einstein is a famous example), it is also possible for a person to make a deliberate transition from a non-visual way to formulate a problem, to one that is primarily visual in nature. As a young man, Benoit Mandelbrot taught himself to translate algebraic problems into geometric forms, in order to solve 5 them (“translating algebra back into geometry, and then thinking in terms of geometric shapes”Mandelbrot 2012:70). Another person who taught himself to think in diagrams as a young man is Charles Sanders Peirce (Kent 1987:3). Since the ideas of Peirce on how to use diagrams are close to the ones that will be advocated in this position paper, it may be helpful to describe his ideas on this topic. Peirce’s main discussion of diagrams can be found in his work on logic, from the early 1870s and onwards (e.g. Misak 2010:84). His best-known work in this genre is his so-called system of existential graphs. Peirce’s hope for these graphs was huge, namely to produce “a moving picture of the action of the mind in thought” (Peirce cited in Pietarinen 2006:104). Peirce presented his ideas on existential graphs in an article called “Prolegomena to an Apology for Pragmaticism” (1906). Existential graphs or logical diagrams, as Peirce also calls them, are simple in nature and consist of words in combination with simple figures, constructed with the help of dots and lines. At the most fundamental level, what they show is how some logical proposition stands in relation to some other logical propositions. “A diagram”, according to Peirce, “is a kind of icon particularly useful, because it suppresses a quantity of details, and so allows the mind more easily to think of the important features” (Peirce 1998:13). “Many diagrams”, he also says, “resemble their objects not at all in looks; it is only in respect to the relations of their parts that their likeness consists” (ibid.). One reason that makes it possible to also explore new ideas with the help of existential diagrams is that each of the parts that make up the graph does not have a fully determinate meaning. Another is that each part is related to other parts; and the logician can experiment with changing their internal relations in various ways: add a link, remove one, and so on. Deductive reasoning of the diagrammatic type, in other words, has an abductive quality to it. This abductive quality can be heightened with the help of experiments: one can make exact experiments upon uniform diagrams; and when one does so, one must keep a bright outlook for unintended and unexpected changes thereby brought about in the relations of different significant parts of the diagram to one another. Such 6 operations upon diagrams, whether external or imaginary, take the place of the experiments upon real things that one performs in chemical and physical research. (Peirce 1906:493) It is clear that Peirce’s system of existential graphs is very special in nature and probably not suitable for the social sciences. But he also experimented with other kinds of diagrams, including ones that were used in empirical research. This is, for example, how he described Kepler’s discovery of the elliptical form of the trajectory of the planets: His admirable method of thinking consisted in forming in his mind a diagrammatic or outline representation of the entangled state of things before him, omitting all that was accidental, observing suggestive relations between the parts of his diagram, performing diverse experiments upon it, or upon the natural objects, and noting the results. (Peirce 1966:255) # 3. Sociological Diagrams for Theorizing Similar to the kind of diagrams that Kepler used, sociological diagrams of the theorizing type should ideally be heuristic as well as oriented to empirical problems. This means that besides using the conventional tools when you create a diagram – geometric forms of various shapes, notations and so on – a sociological diagram of the theorizing type also has to somehow help the analyst to capture distinctly sociological phenomena. This means that this type of diagram should in principle be able to capture such items as social structure, social action and social forms. More concretely, what should a theorizing sociological diagram look like? One way to answer this would be to look at the existing sociological literature and look at the diagrams we can find there. Somewhat disappointingly, I have only been able to find one single sociological diagram that comes close to being a theorizing diagram. This is the famous diagram by James Coleman in which he attempts to show the relationship between macro- and micro forms of social action. While Coleman may well have meant his diagram to function as a theory picture, it has two qualities that make it possible to also view it as something of a theorizing diagram. First of 7 all, it is open (even if this quality may well be unintended). Secondly, it is squarely focused on a critical and still unsolved problem in sociology, namely the micro-macro transition. If you take a close look at the Coleman diagram, it becomes clear how Coleman constructed it. The micro-macro dimension is represented through the devise of two parallel lines. The reader’s sense of dealing with a process is created in the following way. First, this is how you experience the diagram as you make your way through it, going from macro to micro, from micro to micro, and then back up again to macro. Secondly, the slanted lines down (1) and up (3) in the trapezoid have been positioned in such a way that they signal movement or process to the reader. Sometimes the Coleman diagram is referred to as a boat or a bath tub - but never as a box. This indicates that the angled lines are important to the general structure of the diagram. Coleman’s diagram is open in the sense that it is unfinished or ambiguous to some degree, and therefore invites the reader to work on it and complete it. There exists today a number of studies that use Coleman’s diagram but have change it in some way (Hedström and Ylikoski 2010; Abell, Felin and Foss 2008; Vromen 2010; Jepperson and Meyer 2011). In my own view, each of the transitions in the Coleman diagram are open to interpretation and address a central and difficult problem in sociology. The micro to macro transition, for example, can be the result of aggregation, emergence or the confrontation with an already existing social structure. The macro to micro transition can take the form of, say, imitation, coercion or influence. And the micro to micro transition may represent a process that entails a superficial transmission, a reinforcement of existing ideas, or a change of the whole meaning structure from one topic to another (as when Coleman used his diagram to capture Weber’s argument in The Protestant Ethic). Regardless if we decide that Goleman’s diagram is of the theorizing version or not, is it possible to create theorizing diagrams in sociology; and if so, what would these look like? My sense is “yes”; and I will now present my own modest attempt in this direction (for a fuller description, see my paper). I begin its construction by visually representing a social relationship according to Max Weber (see the end of the paper for the various stages of the diagram) . This means that you have two actors; that these two actors orient their actions to each other; and that they simultaneously 8 orient their actions to an order. I then take an insight from Peirce’s semiotics, which in all brevity is that signs impact interpretants. Translated into sociology and the Weber model, this means that the order impacts the participants. All of this can be cast in the form of Coleman’s “boat” – but with the important addition that the concept of meaning is now part of the model. What makes this diagram into a theorizing diagram that can be used to further develop theory? My tentative answer is that if you take this model and confront it with some concrete, empirical situation, you may quickly notice that various adjustments to the model need to be made. Maybe the relationship is asymmetrical; maybe the order is disintegrating; maybe the actors are unable to understand the order; and so on. At this point of my argument I also want to reiterate a theme in my paper, namely that diagrams are not to be understood as visual models that can be nicely reproduced in articles or books. They are tentative models to be used during the research and then discarded # 4. Some Mini-Concluding Remarks Charts, tables, and diagrams of a qualitative sort are not only ways to display work already done; they are very often genuine tools of production… Most of them flop, in which case you have still learned something. When they work, they help you to think more clearly and to write more explicitly. They enable you to discover the range and the full relationships of the very terms with which you are thinking and of the facts with which you are dealing. - C. Wright Mills, The Sociological Imagination By way of much too brief conclusion it should first of all be repeated that we currently do not know how to create sociological diagrams: what they should look like, and what parts they should be made of. In the meantime, however, it would seem fruitful for sociologists who are interested in theorizing to pay more attention to the role of visual thinking with the help of diagrams, and perhaps also to the visual culture of sociology more generally. 9 Reasoning is multimodal in nature, and draws on more than one kind of thinking. This means that one way to increase the power of theorizing in sociology is to explore and cultivate other ways of reasoning than the traditional ones. A last point, but one that is important to me and my project of theorizing, is the following. In teaching students how to theorize, it is important that they have also some training in how to construct and use theory pictures and theorizing diagrams. I think they would benefit from this knowledge –and also enjoy trying to develop their ideas through visual means of this type. *** Fig. 1. Max Weber on Social Action and Social Interaction (#1-#2) #1. Social Action with Orientation to Another Actor and to an Order Order Actor # 1 Actor # 2 # 2 Social Interaction with Two Actors Orienting Themselves Also to an Order Order Actor # 1 Actor # 2 Comment: According to Max Weber in Economy and Society, social action is defined as the action of an actor that is invested with meaning and oriented to an actor and/or an order. Interaction takes place when two actors orient their action to each other and/or to an order. 10 Fig. 2. The Models of Weber and Peirce Combined Order Actor # 1 Actor # 2 Comment: Actors # 1 and # 2 are interacting, as indicated by the non-broken lines (2). Both orient themselves to an order (4) – while being influenced by this order at the same time (1, 3) Fig. 3. A Theorizing Diagram Based for Social Interaction Order or Field 1 3 2 Actor #1 Actor # 2 Comment: Actors # 1 and # 2 are interacting, as indicated by the non-broken lines (2). Both orient themselves to an order (or field; 4) – while being influenced by this order at the same time (1, 3). This figure differs from the preceding in that it has been given a shape that is reminiscent of the Coleman diagram and which better captures the processual element in continuous interaction.