Fulfilling Higher Education's Covenant with Society: The

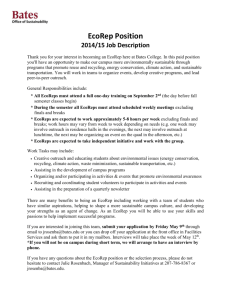

advertisement