International Journal of Food Microbiology 60 (2000) 205–218

www.elsevier.nl / locate / ijfoodmicro

New developments in chromogenic and fluorogenic culture media

M. Manafi*

Hygiene Institute, University of Vienna, Kinderspitalgasse 15, A-1095 Vienna, Austria

Abstract

This review describes some recent developments in chromogenic and fluorogenic culture media in microbiological

diagnostic. The detection of b-D-glucuronidase (GUD) activity for enumeration of Escherichia coli is well known. E. coli

O157:H7 strains are usually GUD-negative and do not ferment sorbitol. These characteristics are used in selective media for

these organisms and new chromogenic media are available. Some of the new chromogenic media make the Salmonella

diagnostic easier and faster. The use of chromogenic and fluorogenic substrates for detection of b-D-glucosidase (b-GLU)

activity to differentiate enterococci has received considerable attention and new media are described. Rapid detection of

Clostridium perfringens, Listeria monocytogenes, Bacillus cereus and Staphylococcus aureus are other application of

enzyme detection methods in food and water microbiology. 2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Microbiology; Fluorogenic; Chromogenic; Culture media; Rapid identification

1. Introduction

The ability to detect the presence of a specific and

exclusive enzyme using suitable substrates, in particular fluorogenic or chromogenic enzyme substrates, has led to the development of a great number

of methods for the identification of microorganisms

even in primary isolation media. The incorporation

of such substrates into a selective medium can

eliminate the need for subculture and further biochemical tests to establish the identity of certain

microorganisms (Manafi et al., 1991; Manafi, 1996).

This review describes recent developments in fluorogenic and chromogenic media for specific detection

of microorganisms.

*Tel.: 1 43-1-40490-79450; fax: 1 43-1-40490-9794.

E-mail address: mohammad.manafi@univie.ac.at (M. Manafi).

The fluorogenic enzyme substrates generally consist of a specific substrate for the specific enzyme

such as sugar or amino acid and a fluorogen such as

4-methylumbelliferone, being able to convert UV

light to visible light. Methylumbelliferyl-substrates

are water soluble, highly sensitive and very specific.

Because of their pH-dependance, strong diffusion in

solid media and the need of UV-light, the use of

these substrates is limited. Chromogenic enzyme

substrates are compounds which act as the substrate

for specific enzymes and change colour due to the

action of the enzyme. In general, based on their

chemical reaction, four groups of chromogenic compounds can be distinguished and recently described

by Manafi (1998). Indolyl derivatives are water

soluble and heat stable and the mostly used derivatives such as 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl (X), 5bromo-6-chloro-3-indolyl (magenta) or 6-chloro-3-

0168-1605 / 00 / $ – see front matter 2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

PII: S0168-1605( 00 )00312-3

206

M. Manafi / International Journal of Food Microbiology 60 (2000) 205 – 218

indolyl (salmon) showing no diffusion on the agar

plate.

2. The application of chromogenic and

fluorogenic media in food and water

microbiology

2.1. Enterobacteriaceae

2.1.1. Escherichia coli

The new generation of media uses b-D-glucuronidase (GUD) as indicator for E. coli. GUD is present in

94–96% of E. coli strains, but also some Salmonella,

Shigella and Yersinia spp. (Hartman, 1989). Some

authors found GUD-positive strains of Citrobacter

freundii (Gauthier et al., 1991) or some strains of

Klebsiella oxytoca, Serratia fonticola and Yersinia

intermedia (Alonso et al., 1996). GUD test is used

increasingly for detection of E. coli in water and

food microbiology as E. coli is an important indicator of fecal contamination in samples from the

food processing and water purification plants. Other

Escherichia spp. do not produce this enzyme as

described by Rice et al. (1991). Some pathogenic

strains of E. coli such as typical E. coli O157:H7

however, do not posses GUD either (Frampton and

Restaino, 1993).

GUD activity is measured by using different

chromogenic and fluorogenic substrates such as pnitrophenol-b-D-glucuronide (PNPG), or 5-bromo-4chloro-3-indolyl-b-D-glucuronide (X-GLUC) and 4methylumbelliferyl-b-D-glucuronide (MUG). MUG

is hydrolyzed by GUD yielding 4-MU, which shows

blue fluorescence when irradiated with long-wave

UV light (366 nm). MUG has been incorporated into

both liquid media including lauryl sulfate broth,

m-Endo broth, EC broth, Brila-broth, DEV-lactosepepton-broth and LMX broth. The solid media to

which MUG was added, include violet red bile agar,

ECD-agar, MacConkey-agar and m-FC agar and are

already described earlier (Manafi, 1996). Fluorocult

media (Merck) are used for determination of E. coli,

e.g. in drugs (Huang et al., 1994), in foods of animal

origin (Bredie and de Boer, 1992), for the isolation

of diarrhea-causing E. coli (Muto et al., 1991),

clinical samples (Heizmann et al., 1988; Mori et al.,

1991), milk and milk products (Hahn and Wittrock,

1991) and bathing water (Havemeister, 1991). The

minimum concentration sufficient for distinct indication was 50 mg / ml. However, the concentration

necessary for acceptable detection of E. coli depends

on the other constituents of the media. As the

fluorescence of 4-MU is pH dependent, the pH of

growth media containing MUG should be slightly

alkaline; otherwise alkaline solution needs to be

added to reveal fluorescence. MUG can be sterilized

together with other medium ingredients without loss

of activity; furthermore, no inhibitory effect on E.

coli growth has hitherto been observed. The disadvantage of incorporating MUG into solid media is

that fluorescence diffuses rapidly from the colonies

into the surrounding agar. MUG methodes are cited,

e.g. in DIN 10 110 ‘Determination on E. coli in meat

and meat derivates’, DIN 10 183, part 3 ‘Determination of E. coli in milk, milk derivates, icecream,

baby food based on milk or ISO 11866-2 ‘Enumeration of presumptive E. coli – Part 2: most probable

number technique using MUG’.

A new chromogenic selective agar for the detection of E. coli is TBX Agar. TBX is a modification of Tryptone bile agar to which the substrate

5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-b-D-glucuronide

(XGLUC or BCIG) is added. GUD cleaves the

chromogenic substrate BCIG and the released chromophore causes distinct and easy to read blue-green

coloured colonies of E. coli. Furthermore TBX Agar

complies with the ISO / DIS Standard 16649 for the

enumeration of E. coli in food and animal feeding

stuffs.

On a solid medium containing 8-hydroxyquinoline-b-D-glucuronide (HQG) (200 mg / l) and a

ferric salt, b-glucuronidase positive strains grow as

black colonies. The pigment is located only in the

colony mass. The product of hydrolysis is 8-hydroxyquinoline, which forms black complexes with

ferrous and ferric ions. The commercially available

medium Uricult-Trio (Orion Diagnostica) contains

HQG. Of 324 E. coli strains isolated from urine

samples, 92% grew black-brown colonies on dipslide, thus being b-glucuronidase positive (Larinkari

and Rautio, 1995).

2.1.2. E. coli O157: H7

E. coli O157:H7 is an important food-borne

pathogen and can cause diarrhea, hemorrhagic colitis, and hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS). The agar

medium most commonly used for the isolation of E.

M. Manafi / International Journal of Food Microbiology 60 (2000) 205 – 218

coli O157:H7 is Sorbitol-MacConkey agar (SMAC,

March and Ratnam, 1986). Strains of E. coli

O157:H7, unlike the majority of E. coli strains, do

not ferment D-sorbitol within 24 h and are GUDnegative and do not grow at 45.58C. Sorbitol-nonfermenting colonies, indicative of the typical E. coli

O157:H7, are colourless on this medium. SMAC

agar is not generally useful for Shiga-like-toxin

(Stx)-producing E. coli strains of serotypes other

than O157:H7 because no known genetic linkage

exists between Stx production and sorbitol fermentation. E. coli O157:H7 also does not ferment

rhamnose on agar plates, in contrast to the majority

of other sorbitol-nonfermenting strains. The selectivity of SMAC agar has been improved with the

addition of cefixime-rhamnose (CR-SMAC, Chapman et al., 1991), cefixime-tellurite (CT-SMAC

agar, Zadik et al., 1993), MSA-MUG (Szabo et al.,

1986) and BCIG-SMAC (Okrend et al.,1990). Recently, new selective media have been developed to

increase the effectiveness of E. coli O157:H7 isolation, including Rainbow agar O157 (RB, Biolog Inc.,

Hayward, USA), BCM O157:H7 (BCM, Biosynth

AG, Staad, Switzerland), Fluorocult E. coli O157:H7

(Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and CHROMagar

O157 (CHROMagar, Paris, France).

Fluorocult E. coli O157:H7 is a selective agar for

the isolation and diferentiation of E. coli O157:H7

from food samples and from clinical material. Sodium desoxycholat inhibits the Gram positive bacteria. E. coli O157:H7 strains grow as greenish

colonies and show no fluoresence under UV light.

On RB O157, E. coli strains grow, yielding

colonies ranging in colour through various shades of

red, magenta, purple, violet, blue, and black. The

typical glucuronidase negative strains form distinctive charcoal gray or black colonies. Other

glucuronidase positive strains gave red or magenta

coloured colonies (Bochner, 1995). RB agar shows

good results for isolation when the background flora

is low, or when E. coli O157 is present as a high

proportion (e.g. 5%). Bettelheim (1998b) has evaluated and compared RB agar with SMAC agar. Some

other EHEC also stand out as blue-black, whereas

O113 and some other EHEC strains were mauve, red

or pink. Manafi and Kremsmair (1999) have found

that strains of E. coli O157:H7 could be readily

isolated and recognized by typical black colonies on

RB agar. The mixture tellurite / novobiocin (2.5 mg

207

tellurite and 10 mg novobiocin / l according to Stein

and Bochner, 1998) had inhibited the major background-flora except Hafnia alvei strains isolated

from milk and raw meat. It was found, that RB agar

had a sensitivity and a specificity of 91.1% and

91.6%, respectively using pure cultures and only

2.1% false positive results (H. alvei) analyzing the

food samples.

On BCM agar E. coli O157:H7 strains produce

convex colonies 1.5–2.5 mm in diameter surrounded

by distinct blue / black precipitates. Sorbitol positive

isolates were blue to turquoise. A comparison of

BCM O157:H7 and SMAC-BCIG agars using naturally contaminated beef samples was made using

presumptively positive enrichment broths identified

by various rapid methods. The percent sensitivity

and specificity values were 90.0 and 78.5 for BCM

O157:H7 and 7.0 and 46.4 for SMAC-BCIG. Thus,

BCM O157:H7 ( 1 ) medium displayed greater

sensitivity and specificity than MSA-BCIG for detecting E. coli O157:H7 using artificially and naturally contaminated beef products (Restaino et al.,

1999b). On CHROMagar O157 (Chromagar, Paris,

France) E. coli O157 strains produce pink colonies

(Wallace and Jones, 1996; Bettelheim, 1998a). A

collaborative evaluation of detection methods for E.

coli O157:H7 from radish sprouts and ground beef

using plating and immunological methods is described by Onoue et al. (1999). The plating media

tested were CT-SMAC, BCM O157 and

CHROMagar O157. E. coli O157:H7 was recovered

well from ground beef by all of the methods except

direct plating with SMAC. For radish sprouts, the

IMS-plating methods with CT-SMAC, BCM O157

and CHROMagar O157 were most efficient.

A study was done by Taormina et al. (1998) to

recover E. coli O157:H7 cells from unheated and

heated ground beef, and to compare the ability of

five enrichment broths to recover E. coli O157:H7

cells from heated ground beef. Eight selective agars

and two non-selective agars were evaluated for their

ability to support colony formation by E. coli

O157:H7 surviving heat treatment. Of the selective

media tested, modified eosin methylene blue agar

(MEMB) and RB agar O157 supported recovery of

significantly (P , 0.05) higher numbers of heatstressed cells of E. coli O157:H7, regardless of

heating time. Chromagar O157, CT-SMAC and CRSMAC performed poorly, even in unheated samples.

208

M. Manafi / International Journal of Food Microbiology 60 (2000) 205 – 218

SMAC and BCM O157:H7 agar were similar to

CT-SMAC and CR-SMAC in their ability to recover

E. coli O157:H7 from heated beef. TBX agar

performed significantly better than these media, but

was inferior to MEMB agar and RB agar O157:H7.

Enrichment using tryptone soya broth with novobiocin or a procedure using brain heart infusion and

tryptone phosphate broths recovered the highest

population of heat-stressed E. coli O157:H7.

A new medium ‘EOH-agar’ was developed for

identification of E. coli 0157:H7 by Kang and Fung

(1999) and was compared with SMAC agar. Indigo

carmine (0.03 g / l) and phenol red (0.036 g / l) were

found as the best combination for differentiation

between E. coli O157:H7 and other E. coli and

added to the basal agar medium (SMAC medium

excluding neutral red and crystal violet). On the dark

blue EOH medium, E. coli produced a yellow colour

with clear zone, whereas E. coli O157:H7 produced

a red colour without clear zone. The recovery

numbers of E. coli 0157:H7 from inoculated ground

beef, pork, and turkey and of heat- and cold-injured

E. coli O157:H7 also were not significantly different

between SMAC and EOH media (P . 0.05).

2.1.3. Media for simultaneous detection of E. coli

and coliforms

As both E. coli and coliforms are important

indicators of water pollution, there arises the necessity to create media which are able to simultaneously

detect both bacteria. This would then guarantee a

better performance of microbiological quality control. The new enzymatic definition of coliforms,

which is not method related, is the possession of

b-D-galactosidase gene which is responsible for the

cleavage of lactose into glucose and galactose by the

enzyme b-D-galactosidase. The determination of bgalactosidase is accomplished by using o-nitrophenyl-b-D-galactopyranoside (ONPG), p-nitrophenyl-b-D-galactopyranoside (PNPG), 6-bromo-3indolyl-b-galactopyranoside (Salmon-Gal), 5-bromo4-chloro-3-indolyl-b-D-galactopyranoside (XGAL)

or

6-bromo-2-naphthyl-b-D-galactopyranoside

(BNGAL),

8-hydroxychinoline-b-D-galactoside,

cyclohexenoesculetin-b-D-galactoside and fluorogenic 4-methylumbelliferyl-b-D-galactopyranoside

(MUGAL). Attempts were made to enhance the

coliform assay response by adding 1-isopropyl-b-Dthiogalactopyronaside (IPTG) to the media (Manafi,

1995) or sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (Berg and

Fiksdal, 1988) increasing the b-D-galactosidase activity by improving the transfer of the substrate

and / or enzyme across the outer membrane.

Commercially available media have been developed which permit rapid simultaneous detection

of E. coli and coliforms in water (Table 1). These

media contain a variety of enzyme substrates for

detection of b-D-galactosidase (presence of

coliforms) and b-D-glucuronidase (presence of E.

coli), and have previously been reviewed (Manafi et

al., 1991; Manafi, 1996).

2.1.3.1. Liquid commercially available media for the

detection of E. coli and coliforms

The Colilert system, containing ONPG / MUG,

simultaneously detects the presence of both total

coliforms and E. coli. After incubation, the formula

becomes yellow if total coliforms are present and

fluorescent under long-wavelength (366 nm) ultraviolet light if E. coli is in the same sample. Schets et

al. (1993) compared Colilert with Dutch standard

enumeration methods for E. coli and coliforms in

water and have found, that Colilert gave false-negative results in samples with low numbers of E. coli

or total coliforms, indicating that the Colilert does

not always support the growth of environmental E.

coli or coliforms. They regarded the Colilert as

unsuitable for monitoring water samples in comparison to Dutch standard method. Another study by

Landre et al. (1998) reported the false positive

coliform reaction mediated by Aeromonas spp. in the

Colilert system. Data obtained clearly demonstrate

that A. hydrophila can elicit a positive coliform type

reaction at very low densities. Cell suspensions as

low as 1 cfu / ml were observed to yield a positive

reaction. Similar results were obtained with other

members from the mesophilic group of aeromonads.

Use of Colilert for monitoring water quality will lead

to overestimation of coliforms as Aeromonas spp.

are known to be present in treated drinking water

supplies. Development of blue-green color in an

initially light yellow coloured solution, indicate the

presence of coliforms using LMX broth or

Readycult Coliforms, containing Xgal / MUG. Fluorescence at 366 nm in the same vessel denoted the

presence of E. coli. An evaluation of a number of

presence / absence (P/A) tests for coliforms and E.

coli, including LMX broth (Merck) and Colilert

M. Manafi / International Journal of Food Microbiology 60 (2000) 205 – 218

209

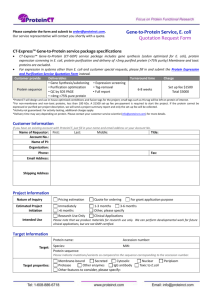

Table 1

Commercially available media for the detection of E. coli and coliforms (updated from Manafi, 1996)a

Medium

Substrate / colour

Manufacturer

Coliforms

E. coli

Liquid media

Fluorocult LMX broth

Readycult coliforms

ColiLert

Coliquick

Colisure

XGAL / blue-green

XGAL / MUG

ONPG / Yellow

ONPG / Yellow

CPRG / red

MUG / blue fluorescence

MUG / blue fluorescence

MUG / blue fluorescence

MUG / blue fluorescence

MUG / blue fluorescence

Merck (Germany)

Merck (Germany)

IDEXX (USA)

Hach (USA)

IDEXX (USA)

Solid media

Fluorocult R agars

TBX-agar

Uricult Trio

EMX-agar

C-EC-MF-agar

Chromocult

Coli ID

CHROMagar ECC

Rapid’ E. coli 2

E. coli / coliforms

ColiScan

MI-agar

HiCrome ECC

–

–

–

XGAL / blue

XGAL / blue

SalmonGal / red

XGAL / blue

SalmonGal / red

XGAL / blue

SalmonGal / red

SalmonGal / red

MUGal / blue fluorescence

SalmonGal / red

MUG / blue fluorescence

BCIG / blue

HOQ / black

MUG / blue fluorescence

MUG / blue fluorescence

XGLUC / blue-violet

SalmonGlu / Rose-violet

XGLUC / purple

SalmonGlu / purple

XGLUC / purple

XGLUC / purple

Indoxyl / blue

XGLUC / blue

Merck (Germany)

Oxoid (UK), Merck (Germany)

Orion (Finnland)

Biotest (Germany)

Biolife (Italy)

Merck (Germany)

bioMerieux (France)

Chromagar (France)

Sanofi (France)

Oxoid (UK)

MicrologyLab. (USA

Brenner et al. (1993)

Union Carbide (USA)

Other systems

ColiComplete

ColiBag / Water check

Pathogel

E. colite

m-Coliblue

XGAL / blue

XGAL / blue-green

XGAL / blue

XGAL / blue

TTC / red

MUG / blue fluorescence

MUG / blue fluorescence

MUG / blue fluorescence

MUG / blue fluorescence

XGLUC / blue

Biocontrol (USA)

Oceta (Canada)

Charm Sci.(USA)

Charm Sci.(USA)

Hach (USA

a

Abbreviations: ONPG, o-nitrophenyl-b-D-galactopyranoside; Salmon-GAL, 6-bromo-3-indolyl-b-D-galactopyranoside; XGAL, 5-bromo4-chloro-3-indolyl-b-D-galactopyranoside; CPRG, chlorophenol red b-galactopyranoside; XGLUC, 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-b-D-glucuronide; MUG, 4-methylumbelliferyl-b-D-glucuronide; TTC, triphenyl tetrazolium chloride; HOQ, hydroxyquinoline-b-D-glucuronide.

(Idexx) has been published under the Department of

the Environment series in the UK (Lee et al., 1995).

They compared four P/A tests with UK Standard

methods and found that more coliforms were detected than with membrane filtration technique; in

addition, it was shown that results in LMX broth

were the easiest to interpret. The study concludes

that there is no P/A test that is best at all locations

for both coliforms and E. coli, and as there can be

marked ecological differences between sources it is

important that particular P/A tets are validated in

each geographical area before use. The efficiacy and

rapidity of detectable reactions make LMX broth or

Readycult coliforms a very useful tool in routine

water and food microbiology (Hahn and Wittrock,

1991; Betts et al., 1994; Lee et al., 1995; Manafi,

1995; Manafi and Rosmann, 1998). Only a few

non-coliform bacteria such as strains of Serratia

spp., H. alvei, Vibrio metschnikovii, V. vulnificus, A.

hydrophila and A. sobria gave a false positive

reaction with Xgal (Manafi, 1995; Fricker and

Fricker, 1996). This is in accordance with Ley et al.

(1993), who found that Xgal medium, in addition to

providing a rapid test for coliforms, also detected

b-galactosidase-positive aeromonads and nonsheenforming members of the Enterobacteriaceae on mEndo agar. They reported the low sensitivity of

m-Endo for detecting Aeromonas spp. which are

considered ubiquitous waterborne organisms and

should not be present in drinking water (Moyer,

1987). It is suggested adding cefsulodin at 5–10

mg / ml to culture media inhibiting the growth of

Aeromonas and Flavobacterium species (Brenner et

al., 1993; Alonso et al., 1996; Geissler et al., 2000).

210

M. Manafi / International Journal of Food Microbiology 60 (2000) 205 – 218

Results of these studies suggest that cefsulodin may

be a useful selective agent against Aeromonas spp.

which should be included in coliform chromogenic

media when high levels of accompanying flora are

expected.

2.1.3.2. Solid commercially available media for the

detection of E. coli and coliforms

Chromocult coliforms agar (CCA) contains

chromogenic Salmon-GAL and X-GLUC, the growth

of coliforms even sublethal damaged cells is granted

due to use of peptone, pyruvate, sorbit and a buffer

of phosphate. Gram positive and some Gram negative bacteria are inhibited by Tergitol 7. On the

CCA, non-E. coli fecal coliforms (Klebsiella, Enterobacter and Citrobacter) (KEC) were identified

by the production of a salmon to red colour from

b-galactosidase cleavage of the substrate SalmonGAL, while E. coli colonies were detected by the

blue / violet colour, produced by the cleavage of Xglucuronide by b-D-glucuronidase. CCA was compared with the Standard Methods membrane filtration

fecal coliform (mFC) medium for fecal coliform

detection and enumeration (Alonso et al., 1998).

Statistically, there were no significant differences

between fecal coliform counts obtained with the two

media (CCA and mFC agar) and two incubation

procedures (2 h at 378C plus 22 h at 44.58, and

44.58C) as determined by variance analysis. In this

study E. coli represented, on average 70.5–92.5% of

the fecal coliform population. A high incidence of

false negative KEC (19.5%) and E. coli (29.6%)

colonies was detected at 44.58C. The physiological

condition of the fecal coliform isolates could be

responsible for the nonexpression of b-galactosidase

and

b-glucuronidase

activities

at

44.58C.

Byamukama et al. (2000) described the quantification of E. coli contamination with CC agar from

different polluted sites in a tropical environment. It

proved to be efficient and feasible for determining

fecal pollutions in the investigated area within 24 h.

Geissler et al. (2000) compared the performance

of LMX broth, Chromocult Coliform -agar (CC)

and Chromocult Coliform -agar plus cefsulodin (10

mg / ml) (CC-CFS), with Standard Methods multiple

tube fermentation (MTF), for the enumeration of

total coliforms (TC) and E. coli from marine recreational waters. Data from the analysis of variance

showed significant differences (P # 0.05) between

TC counts on CC-CFS and LMX. Disagreement

between the CC-CFS agar and the two commercial

enzyme media, was primarily due to the false

positive results. Background interference was reduced on CC-CFS and the TC counts that were

obtained reflected more accurately the number of

TCs. The results of this study support the validity of

the LMX and CC media for the enumeration of E.

coli in marine waters. Background interference was

reduced on CC-CFS and the TC counts that were

obtained reflected more accurately the number of

TCs. Some authors evaluated agar media incorporating Xgal (Ley et al., 1993; Jermini et al., 1994).

They have found that coliform strains produced

sharp blue colonies on the agar plate because of

insolubility of the indigo dye, which does not alter

the viability of the colonies. The MI agar method

(Brenner et al., 1996) containing indoxyl-b-D-glucuronide (E. coli) and 4-methylumbelliferyl-b-D-galactopyranoside (coliforms), was compared with the

approved method by the use of wastewater-spiked

tap water samples. Overall, weighted analysis of

variance (significance level, 0.05) showed that the

new medium recoveries of total coliforms and E. coli

were significantly higher than those of mEndo agar

and nutrient agar plus MUG, respectively, and the

background counts were significantly lower than

those of mEndo agar ( , 5%). Brenner et al. (1996)

made a comparison of the recoveries of E. coli and

total coliforms from drinking water by the MI agar

method and the USEPA-approved membrane filter

method. The current USEPA-approved membrane

filter method for E. coli requires two media, an MF

transfer, and a total incubation time of 28 h. Since

December 1999, MI agar method is approved for

detecting total coliforms and E. coli under the total

coliforms Rule and for enumerating total coliforms

under the Surface water Treatment Rule in USA.

´

On COLI ID agar (bioMerieux)

coliforms are blue

colour colonies and E. coli are rose colour with a

rose zone around the colonies. Other Gram negative

bacteria are on COLI ID bright rose, small and have

no surounding zone, Gram positives and yeasts are

inhibited. Similar to the Chromocult Coliform agar,

on Coliscan and on CHROMagar ECC, E. coli

colonies are blue-violet, other coliforms are red

colonies. There are two approaches to the Coliscan

method, Coliscan Easygel and Coliscan-membrane

filters. The sample can be added directly into the

M. Manafi / International Journal of Food Microbiology 60 (2000) 205 – 218

bottle of Coliscan Easygel, swirled, poured into a

pretreated petri dish and incubated.

Alonso et al. (1999) compared the performance of

CHROMagarECC (CECC), and CECC supplemented with sodium pyruvate (CECCP) with the

membrane filtration lauryl sulfate-based medium

(mLSA) for enumeration of E. coli and non-E. coli

thermotolerant coliforms such as Klebsiella, Enterobacter and Citrobacter. To establish that they

could recover the maximum coliforms and E. coli

population, they compared two incubation temperature regimens, 41 and 44.58C. Statistical analysis by

the Fisher test of data did not demonstrate any

statistically significant differences (P 5 0.05) in the

enumeration of E. coli for the different media

(CECC and CECCP) and incubation temperatures.

Variance analysis of data performed on Klebsiella,

Enterobacter and Citrobacter counts showed significant differences (P 5 0.01) between Klebsiella, Enterobacter and Citrobacter counts at 41 and 44.58C

on both CECC and CECCP. Analysis of variance

demonstrated statistically significant differences (P 5

0.05) in the enumeration of total thermotolerant

coliforms (TTCs) on CECC and CECCP compared

with mLSA. Target colonies were confirmed to be E.

coli at a rate of 91.5% and Klebsiella, Enterobacter

and Citrobacter of likely fecal origin at a rate of

77.4% when using CECCP incubated at 418C. The

results of this study showed that CECCP agar

incubated at 418C is efficient for the simultaneous

enumeration of E. coli and Klebsiella, Enterobacter

and Citrobacter from river and marine waters.

2.1.4. Other systems for detection of E. coli and

coliforms

Grant (1997) described a membrane filtration

medium (m-Coliblue) which detects total coliforms

(red colonies) and E. coli (blue colonies) simultaneously. Recovery of total coliforms and E. coli on

this membrane filtration (MF) medium was evaluated with 25 water samples and the testing of the

m-ColiBlue24 broth, was conducted according to a

US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA)

protocol. For comparison, this same protocol was

used to measure recovery of total coliforms and E.

coli with two standard MF media, m-Endo broth and

mTEC broth. E. coli recovery on the new medium

was also compared to recovery on nutrient agar

supplemented with MUG. Comparison of specificity,

211

sensitivity, false positive error, undetected target

error, and overall agreement indicated E. coli recovery on m-ColiBlue24 was superior to recovery on

mTEC for all five parameters. Recovery of total

coliforms on this medium was comparable to recovery on m-Endo.

ColiComplete is a paper disc contain MUG and

Xgal and can be used with lauryl tryptose broth in

the MPN test. One paper disc is added to each tube

and after incubation at 358C for 24 h, the tubes are

observed under long-wave UV for the confirmation

of E. coli (blue fluorescence). Blue colouration in the

broth indicates the presence of total coliforms and / or

E. coli (Feldsine et al., 1994).

ColiBag (a pre-sterilized plastic bag), E.colite,

ColiGel and Pathogel are media containing enzyme

substrates Xgal and MUG. ColiGel and Pathogel

contain a gelling agent, which solidifies the sample;

coliforms gave blue colonies and E. coli gave blue

and fluorescent colonies under UV light. ColiPAD

offers a multiple tube fermentation procedure for the

determination of E. coli and coliforms in water and

wastewater.

Japanese and US Food and Drug Administration

standard methods (USDA), as well as two agar plate

methods, were compared with the three commercial

kits using enzyme substrates (Venkateswaran et al.,

1996). The levels of detection of coliforms were high

with the commercial kits (78–98%) compared with

the levels of detection with the standard methods

(80–83%) and the agar plate methods (56–83%).

Among the kits tested, the Colilert kit had highest

level of recovery of coliforms (98%), and the level

of recovery of E. coli as determined by bglucuronidase activity with the Colilert kit (83%)

was comparable to the level of recovery obtained by

the USDA method (87%). Levine’s eosine methylene

blue agar was compared with MUG-supplemented

agar for isolation of E. coli. Only 47% of the E. coli

was detected when eosine methylene blue agar was

used; however, when violet red bile (VRB)-MUG

agar was used, the E. coli detection rate was twice as

high.

2.1.5. Salmonella

The conventional media for the detection of

Salmonella have a very poor specificity creating an

abondance of false positives (such as Citrobacter,

Proteus) among the rare real positive Salmonella.

212

M. Manafi / International Journal of Food Microbiology 60 (2000) 205 – 218

The workload for unnecessary examination of suspect colonies is so high that the real positive

Salmonella colonies might often be missed in routine

testing. The use of new chromogenic and fluorogenic

media make the Salmonella diagnostic easier and

faster.

´

2.1.5.1. SM-ID agar ( bioMerieux

, France)

On SM-ID agar Salmonella colonies are detected

by their distinctive red colouration, while coliforms

appear blue, violet, or colourless. The biochemical

characteristics used with SM-ID medium are acid

formation from glucuronate combined with a neutral

red indicator. Two chromogenic substrates for bgalactosidase (Xgal) and b-glucosidase (Xglu) allow

differentiation of Salmonella (negative) from other

enterobacteria acidifying glucuronate (positive:blue

to purple). The selective agents are bile salts and

brilliant green (Dusch and Altwegg, 1995).

2.1.5.2. Rambach agar ( Merck, Germany)

Rambach agar is composed of propylene glycol,

peptone, yeast extract, sodium deoxycholate, neutral

red, and Xgal. After incubation of plates at 378C for

24 h, the formation of acid from propylene glycol

causes precipitation of the neutral red in Salmonella

colonies yielding a red colour (Rambach, 1990).

Salmonella strains show a bright red colour,

coliforms blue (b-D-galactosidase activity) or violet

(the formation of acid from propylene glycol and

b-D-galactosidase activity) and Proteus spp. remain

colourless. Sodium deoxycholate inhibits the accompanying Gram-positive flora. The main disadvantage

of Rambach agar is that it does not detect S. typhi, S.

paratyphi nor some rare strains such as S. moscow

and S. wassenaar. Furthermore, Salmonella strains

which are able to produce b-D-galactosidase such as

S. arizona or, in particular, subspecies IIIa, IIIb, and

¨

VI, show blue-violet colonies on both media (Kuhn

et al., 1994). Pignato et al. (1995) have observed that

the total analysis time for salmonellae in foods can

be reduced to 48 h by using the combination of

Salmosyst broth (Merck) as a liquid medium and

Rambach agar as isolation plate.

2.1.5.3. MUCAP-test ( Biolife, Italy)

MUCAP is a confirmation test for Salmonella

species based on the rapid detection of caprylate

esterase, using fluorogenic 4-methylumbelliferyl-

caprylate. In the presence of C 8 esterase the substrate

is cleaved with the release of 4-methylumbelliferone

(4-MU). One drop of MUCAP has to be added to

each colony tested on Columbia agar and observed

under UV light (366 nm) for 1–5 min. Strong bluish

fluorescence indicates the presence of Salmonella

spp.The MUCAP test was found to be very sensitive,

rapid and easy to perform but not very specific,

giving many false-positive results. The combination

of the MUCAP test and selective media was more

specific. Since most of the false-positive strains are

oxidase positive, the combination of MUCAP and

the oxidase test is recommended (Humbert et al.,

1989).

2.1.5.4. CHROMagar Salmonella ( CHROMagar,

France)

A comparison of CHROMagar Salmonella

medium (CAS), based on the esterase acitivity, and

Hektoen enteric agar (HEA) for isolation of Salmonellae have been done by Gaillot et al. (1999)

with Salmonella isolates and stool samples. All stock

cultures, including cultures of H 2 S-negative isolates,

yielded typical mauve colonies on CAS while 99%

isolates produced typical lactose-negative, black-centered colonies on HEA. Sensitivities for primary

plating and after enrichment were 95 and 100%,

respectively, for CAS and 80 and 100%, respectively, for HEA. The specificity of CAS (88.9%) was

significantly higher than that of HEA (78.5%; P ,

0.0001).

2.1.5.5. Rainbow Salmonella agar ( Biolog, USA)

The growth of distinctive black colonies of Salmonella on the clear Rainbow Agar makes it easier

to detect Salmonella in mixed cultures. The advantages of using Rainbow Agar Salmonella versus

traditional media is the sensitivity and specificity for

Salmonella species. Even some newer Salmonella

media such as XLT4 utilize additives such as

Tergitol 4 that are inhibitory to S. typhi and S.

choleraesuis.

2.1.5.6. Chromogenic Salmonella esterase agar

( PPR Diagnostics Ltd, UK)

Cooke et al. (1999) described a novel agar

medium, chromogenic Salmonella esterase (CSE)

agar. The agar contains peptones and nutrient extracts together with the following 4-[2-(4-

M. Manafi / International Journal of Food Microbiology 60 (2000) 205 – 218

octanoyloxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-vinyl]quinolinium-1-(propan-3-yl-carboxylic-acid)-bromide (SLPA-octanoate bromide form). SLPA-octanoate is a newly synthesized ester formed from a

C 8 fatty acid and a phenolic chromophore. In CSE

agar, the ester is hydrolyzed by Salmonella spp. to

yield a brightly coloured phenol which remains

tightly bound within colonies. The typical Salmonella strains were burgundy coloured on a transparent

yellow background, whereas non-Salmonella spp.

were white, cream, yellow or transparent. The sensitivity (93.1%) of CSE agar for non-typhi Salmonellae compared favorably with those of Rambach

(82.8%), xylose-lysine-deoxycholate (XLD; 91.4%),

Hektoen-enteric (89.7%), and SM ID (91.4%) agars.

The specificity (93.9%) was also comparable to

those of other Salmonellamedia (SM ID agar,

95.9%; Rambach agar, 91.8%; XLD agar, 91.8%;

Hektoen-enteric agar, 87.8%). Strains of Citrobacter

freundiiand Proteus spp. giving false-positive reactions with other media gave a negative colour

reaction on CSE agar. CSE agar enabled the detection of . 30 Salmonella serotypes, including

agona, anatum, enteritidis, hadar, heidelberg, infantis, montevideo, thompson, typhimurium, and virchow.

2.1.5.7. Compass Salmonella agar ( Biokar diagnostics, France)

Perry and Quiring (1997) described an agar

medium based on the detection of C8-esterase activity

using

5-bromo-6-chloro-3-indolyl-caprylate.

Magenta coloured colonies indicating the presence of

Salmonella spp.

2.1.5.8. Chromogenic ABC medium ( Lab M. Ltd.,

UK)

Perry et al. (1999) described a new chromogenic

agar medium, ABC medium (ab-chromogenic

medium), which includes two substrates, 3,4cyclohexenoesculetin-b-D-galactoside (CHE) and 5bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-a-D-galactopyranoside (XaGal), to facilitate the selective isolation of Salmonella spp. CHE-Galactoside is utilised by most

Enterobacteriaceae, yielding black colonies. The X5-Gal is hydrolysed by Salmonella spp. to produce

characteristic, easy to distinguish, green colonies.

This medium exploits the fact that Salmonella spp.

may be distinguished from other members of the

213

family Enterobacteriaceae by the presence of agalactosidase activity in the absence of b-galactosidase activity. A total of 1022 strains of Salmonella

spp. and 300 other Gram-negative strains were

inoculated onto this medium. Of these, 99.7% strains

of Salmonella spp. produced a characteristic green

colony, whereas only one strain of non-Salmonella

produced a green colony.

2.2. Enterococci

The use of chromogenic and fluorogenic substrates

for detection of b-D-glucosidase activity to differentiate enterococci has received considerable attention

(Dufour, 1980; Littel and Hartman, 1983).

2.2.1. Enterolert and Microtiter plate MUST

4-methylumbelliferyl-b-D-glucoside (MUD), when

hydrolyzed by enterococcal b-D-glucosidase, releases

4-methylumbelliferone, which exhibits fluorescence

under a UV lamp (366 nm). Enterolert (IDEXX

Laboratories Inc., Westbrook, Maine), and a Microtiter plate MUST (Sanofi, France), containing MUD

detecting b-D-glucosidase. Niemi and Ahtiainen

(1995) desribed the evaluation of MTP method with

Slanetz–Bartley and KF-Streptococcus agar using

pure cultures. Both media yielded high recoveries of

the target species. The MUD method tended to give

slightly lower recoveries than the agar cultivation

methods with some target species at 448C but

recoveries were better than at 418C. It has to be

mentioned, that there may be some problems with

other glucosidase positive bacteria such as Aerococcus spp., in particular in natural contaminated water

samples. Budnick et al. (1996) evaluated the Enterolert for enumeration of enterococci in recreational waters as a semiautomated MPN method and

compared with the standard membrane filter method

by parallel testing of 138 marine and freshwater

recreational bathing water samples. No statistical

significant difference and a strong linear correlation

were found between the two methods. Culturing of

501 Enterolert test wells resulted in false-positive

and false-negative rates of 5.1 and 0.4%, respectively.

2.2.2. mEI agar

Dufour (1980) described a medium (mEI agar) for

use in a single-step, 24-h MF procedure to enumerate

214

M. Manafi / International Journal of Food Microbiology 60 (2000) 205 – 218

enterococci in marine water and freshwater. The

medium contained nalidixic acid, cycloheximide,

triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) and indoxyl-bD-glucoside. Enterococci strains produce an insoluble

indigo blue complex, which diffuses into the surrounding media, forming a blue halo around the

colony. Rhodes and Kator (1997) evaluated mEI

agar with respect to specificity and recovery of

enterococci from environmental waters. Extending

incubation from 24 to 48 h improved enterococci

recovery but 77% of the colonies classified as nontarget were confirmed as enterococci. Decreasing the

concentration of or eliminating indoxyl-b-D-glucoside from mE did not significantly affect recovery of

purified isolates. Messer and Dufour (1998) recently

modified the medium by reducing the TTC from 0.15

to 0.02 g / l and adding 0.75 g of indoxyl b-Dglucoside per liter. The new MF medium, mEI

medium, detected levels of enterococci in 24 h

comparable to those detected by the original mE

medium in 48 h, with the same level of statistical

confidence. The comparative recovery studies, specificity determinations, and multilaboratory evaluation indicated that mEI medium has analytical performance characteristics equivalent to those of mE

medium. The simplicity of use and decreased incubation time with mEI medium will facilitate the

detection and quantification of enterococci in fresh

and marine recreational waters.

2.2.3. Chromocult enterococci broth ( CEB) and

Readycult enterococci

Using chromogenic substrate 5-bromo-4-chloro-3indolyl-b-D-glucopyranoside (XGLU), Chromocult

Enterococci broth (CEB) (Merck) and Readycult

Enterococci (Merck) utilises the b-D-glucosidase

reaction as an indicator of the presence of enterococci. XGLU is liberated and rapidly oxidized to

bromochloroindigo which produces blue colour in

Chromocult broth as well as blue coloured enterococci colonies in Chromocult Enterococci agar.

Other b-D-glucosidase-producing organisms being

suppressed by the sodium azide content of the broth

(Manafi and Windhager, 1997). The results obtained

with pure cultures showed that 97% of the strains,

which gave positive results, were identified as enterococci (E. fecalis, E. faecium, E. durans, E.

casseliflavus and E. avium). The false-positive

strains (3%) were Leucononostoc, Lactococcus lactis

lactis and Aerococcus spp. No false-negative results

were found. This medium was used to enumerate

enterococci in water using a presence / absence procedure and gave still positive results with 10 cfu / 100

ml water samples after 24 h incubation.

2.2.4. RAPID9 enterococcus agar

RAPID9 enterococcus agar (Sanofi, France) is a

new medium using chromogenic Xglu for the detection of enterococci and a selective mix for the

inhibition of Gram negative and other b-glucosidase

positive bacteria other than enterococci.

2.2.5. Comparative studies

In most literature, Slanetz and Bartley (1957) agar

is treated as a suitable MF medium to detect fecal

´ and

enterococci from a water sample. Amoros

Alonso (1996) presented a study including a comparison of Slanetz–Bartley agar and Enterococci agar

(with XGLU) using samples of irrigation channels

and seawater. They found no statistical differences

between both media in seawater, although the specifity of the Enterococci agar decreased in marine

water and there was a considerable number of falsepositives.

2.3. Staphylococcus aureus

On the new chromogenic medium, CHROMagarE

S. aureus medium (CHROMagar, France), colonies

of S. aureus are typical pink coloured. In supplementing CHROMagar S. aureus with an appropriate

antibiotic, for instance methicillin, one can obtain

information related to some methicillin resistant S.

aureus strains. This medium has been evaluated by

using pure cultures and clinical specimens. Out of

the 181 S. aureus and 81 coagulase negative Staphylococcus strains belonging to 18 different species, S.

aureus, S. epidermidis, S. caprae and S. schleiferi

strains yielded pink colonies (Freydiere et al., 2000).

2.4. Clostridium perfringens

The identification of C. perfringens is possible

using Fluorocult TSC-agar (Merck, Germany) using

a fluorogenic enzyme substrate. D-Cycloserine inhibits the accompanying bacterial flora and causes the

colonies to remain smaller. C. perfringens colonies

can be detected using 4-MU-phosphate. Acid phos-

M. Manafi / International Journal of Food Microbiology 60 (2000) 205 – 218

phatase is a highly specific indicator for C. perfringens which shows a light blue fluorescence on this

medium (Baumgart et al., 1990).

2.5. Bifidobacteria and lactic acid bacteria

The use of chromogenic X-a-D-galactoside for

differential enumeration of Bifidobacterium spp. and

lactic acid bacteria was described by Chevalier et al.

(1991). The X-a-D-galactoside-based medium is

useful to identify bifidobacteria among Lactobacillus

or Streptococcus strains. Bifidobacteria shows blue

coloured colonies on the agar plate.

2.6. Listeria monocytogenes

L. monocytogenes is a human and animal pathogen

that is widespread in nature. The organism is a

transient constituent of the intestinal flora excreted

by 1–10% of healthy humans. It is an extremely

hardy organism and can survive for many years in

the cold in naturally infected sources. L. monocytogenes has been isolated from a wide variety of foods,

including dairy products, meats, and fish. Although

most of the foodborne listeriosis outbreaks have been

linked to the consumption of dairy products, recent

sporadic cases have been associated with meats, as

well as other foods. All strains of L. monocytogenes

are pathogenic by definition although some appear to

be more virulent than others. Cultural methodology

for isolating the organism from foods has been in a

state of flux since 1985.

2.6.1. BCM L. monocytogens detection system

The new BCM L. monocytogens detection system

(BCM-LMDS, Biosynth, Switzerland) consists of a

selective pre-enrichment broth, selective enrichment

broth, selective / differential plating medium, and

identification on a confirmatory plating medium. The

BCM pre-enrichment broth, allowed the growth of

Listeria and resuscitation of heat-injured L. monocytogenes, which contains the fluorogenic substrate

4-methylumbelliferyl-myo-inositol-1-phosphate and

detects phosphatidylinositol phospholipase C (PIPLC) activity, provided a presumptive positive test

for the presence of pathogenic L. monocytogenes and

L. ivanovii after 24 h at 358C. On BCM-plating

medium, L. monocytogenes and L. ivanovii were the

two Listeria species forming turquoise convex

215

colonies (1.0–2.5 mm in diameter) from PI-PLC

activity on the chromogenic substrate, 5-bromo-4chloro-3-indoxyl-myo-inositol-1-phosphate.

L.

monocytogenes was distinguished from L. ivanovii

by either its fluorescence on BCM confirmatory

plating medium or acid production from rhamnose.

False-positive organisms (Bacillus cereus, S. aureus,

B. thuringiensis, and yeasts) were eliminated by at

least one of the media in the BCM LMDS. The

efficacy of the BCM-LMDS was determined using

pure cultures and naturally and artificially contaminated environmental sponges (Restaino et al.,

1999a). In an analysis of 162 environmental sponges

from facilities inspected by the US Department of

Agriculture (USDA), the values for identification of

L. monocytogenes by BCM LMDS and the USDA

method were 30 and 14 sites, respectively, with

sensitivity and specificity values of 85.7 and 100.0%

vs. 40.0 and 66.1%, respectively. No false-positive

organisms were isolated by BCM LMDS, whereas

26.5% of the sponges tested by the USDA method

produced false-positive results.

2.6.2. Rapid L’ MONO agar

Rapid L’MONO agar (Sanofi, France) is based on

the detection of phosphatidylinositol phospholipase

C and Xylose fermentation. In this way, the colonies

of L. ivanovii appear blue sourrounded by a yellow

halo (Xylose positive) whilst the colonies of L.

monocytogenes are blue without the halo (Xylosenegative). The colonies of other Listeria spp. remain

white because they do not posses phosphatidylinositol phospholipase C activity. Further evaluation of

these media is still needed.

2.7. Bacillus cereus

BCM B. cereus and B. thuringiensis plating

medium (Biosynth, Switzerland) is a differential and

selective medium which alows B. cereus and B.

thuringiensis to grow, but inhibits growth of many

potential false positives including other Bacillus

species. Based on the detection of phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (PI-PLC) activity by

Bacillus species, B. cereus and B. thuringiensis

strains produce turquoise flat dull colonies with and

without turquoise halos to the enzymatic reaction of

PI-PLC with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoxyl-myoinositol-1-phosphate.

216

M. Manafi / International Journal of Food Microbiology 60 (2000) 205 – 218

3. Conclusions

Rapid detection and identification of microorganisms is of high importance in a diverse array of

applied and research fields. By incorporation of

synthetic enzyme substrates into primary isolation

media, enumeration and detection can be performed

directly on the isolation plate. These enzyme substrates have proved to be a powerful tool, utilizing

specific enzymatic activities of certain microorganisms. Many of them are offering enhanced accuracy

and performance to the microbiologist. The incorporation of such substrates into a selective medium can

eliminate the need for subculture and further biochemical tests to establish the identity of certain

microorganisms. These enzymatic assays may constitute an alternative method for enumerating microorganisms in water and foods, which is specific,

sensitive and rapid.

4. Uncited reference

Okrend et al., 1990.

References

Alonso, J.L., Amoros, I., Alonso, M.A., 1996. Differential susceptibility of Aeromonads and coliforms to Cefsulodin. Appl.

Environ. Microbiol. 62, 1885–1888.

Alonso, J.L., Soriano, A., Carbajo, O., Amoros, I., Garelick, H.,

1999. Comparison and recovery of Escherichia coli and

thermotolerant coliforms in water with a chromogenic medium

incubated at 41 and 44.58C. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65,

3746–3749.

Alonso, J.L., Soriano, K., Amoros, I., Ferrus, M.A., 1998.

Quantitative determination of E. coli and fecal coliforms in

water using a chromogenic medium. J. Environ. Sci. Health 33,

1229–1248.

´ I., Alonso J.L., 1996. Determination of Enterococci in

Amoros,

fresh and marine waters with a chromogenic medium, Health

Related Water Microbiology, IAWQ, Mallorca.

Baumgart, J., Baum, O., Lippert, S., 1990. Schneller and direkter

Nachweis von Clostridium perfringens. Fleischwirtschaft 70,

1010–1014.

Berg, J.D., Fiksdal, L., 1988. Rapid detection of total and fecal

coliforms in water by enzymatic hydrolysis of 4-methylumbelliferone-b-D-galactoside. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54, 2118–

2122.

Bettelheim, K.A., 1998a. Reliability of CHROMagar O157 for the

detection of enterohaemorrhagic E. coli EHEC O157 but not

EHEC belonging to other serogroups. J. Appl. Microbiol. 85,

425–428.

Bettelheim, K.A., 1998b. Studies of E. coli cultured on Rainbow

agar O157 with particular reference to enterohaemorrhagic E.

coli EHEC. Microbiol. Immunol. 42, 265–269.

Betts, R., Murray, K., MacPhee, S., 1994. Evaluation of Fluorocult LMX broth for the simultaneous detection of total

coliforms and E. coli. Technical Memorandum No. 705,

Campden Food and Drink Research Association, UK.

Bochner, B.R., 1995. Rainbow Agar VTEC, a new chromogenic

culture medium for detecting verotoxin-producing E. coli,

Abstracts of the Australian Society for Microbiology, Poster

2.1.

Bredie, W.L., de Boer, E., 1992. Evaluation of the MPN, Anderson-Baird-Parker, Petrifilm E. coli and Fluorocult ECD method

for enumeration of E. coli in foods of animal origin. Int. J.

Food Microbiol. 16, 197–208.

Brenner, K., Rankin, C.C., Roybal, Y.R., Stelma J.R., G.R.,

Scarpino, P.V., Dufour, A.P., 1993. New medium for simultaneous detection of total coliforms and E. coli in water. Appl.

Environ. Microbiol. 59, 3534-3544.

Brenner, K.P., Rankin, C.C., Sivaganesan, M., Scarpino, P.V.,

1996. Comparison of the recoveries of E. coli and total

coliforms from drinking water by the MI agar method and the

US environmental protection agency-approved membrane filter

method. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62, 203–208.

Budnick, G.E., Howard, R.T., Mayo, D.R., 1996. Evaluation of

Enterolert for enumeration of enterococci in recreational waters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62, 3881–3884.

Byamukama, D., Kansiime, F., Mach, R.L., Farnleitner, A.H.,

2000. Determination of E. coli contamination with chromocult

coliform agar showed a high level of discrimination efficiency

for differing fecal pollution levels in tropical waters of

Kampala. Uganda. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 864–868.

Chapman, P.A., Siddons, C.A., Zadik, P.M., Jewes, L., 1991. An

improved selective medium for the isolation of E. coli O:157.

J. Med. Microbiol. 35, 107–110.

Chevalier, P., Roy, D., Savoie, L., 1991. X-a-Gal-based medium

for simultaneous enumeration of bifidobacteria and lactic acid

bacteria in milk. J. Microbiol. Methods 13, 75–83.

Cooke, V.M., Miles, R.J., Price, R.G., Richardson, A.C., 1999. A

novel chromogenic ester agar medium for detection of Salmonella. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 807–812.

Dufour, A.P., 1980. A 24-hour membrane filter procedure for

enumerating enterococci. Abstr. Q-69, p. 205. 80th American

Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC, USA.

Dusch, H., Altwegg, M., 1995. Evaluation of five new plating

media for isolation of Salmonella species. J. Clin. Microbiol.

33, 802–804.

Feldsine, P.T., Falbo-Nelson, M.T., Hustead, D., 1994.

Colicomplete substrate-supporting disc method for confirmed

detection of total coliforms and E. coli in all foods. Comparative study. J. AOAC Int. 77, 58–63.

Frampton, E.W., Restaino, L., 1993. Methods for E. coli identification in food, water and clinical samples based on b-glucuronidase detection. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 74, 223–233.

Freydiere, A.M, Bes, M., Roure, C., Carricajo, A., 2000. A new

chromogenic medium for the rapid presumptive identification

M. Manafi / International Journal of Food Microbiology 60 (2000) 205 – 218

of Staphylococcus aureus. Abstr C 230, 100th American

Society for Microbiology, Los Angeles, USA.

Fricker, E.J., Fricker, C.R., 1996. Use of two presence / absence

systems for the detection of E. coli and Coliforms from water.

Water Res. 30, 2226–2228.

Gaillot, O., DiCamillo, P., Berche, P., Courcol, R., Savage, C.,

1999. Comparison of CHROMagar Salmonella medium and

Hektoen enteric agar for isolation of Salmonellae from stool

samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37, 762–765.

Gauthier, M.J., Torregrossa, V.M., Babelona, M.C., Cornax, R.,

Borrego, J.J., 1991. An intercalibration study of the use of

4-methylumbelliferyl-b-D-glucuronide for the specific enumeration of E. coli in seawater and marine sediments. Syst. Appl.

Microbiol. 14, 183–189.

´ I., Alonso, J.L., 2000. QuantitaGeissler, K., Manafi, M., Amoros,

tive determination of total coliforms and E. coli in marine

waters with chromogenic and fluorogenic media. J. Appl.

Bacteriol. 88, 280–285.

Grant, M.A., 1997. A new membrane filtration medium for

simultaneous detection and enumeration of E. coli and total

coliforms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63, 3526–3530.

Hahn, G., Wittrock, E., 1991. Comparison of chromogenic and

fluorogenic substances for differentiation of coliforms and E.

coli in soft cheese. Acta Microbiol. Hung. 38, 265–271.

Hartman, P.A., 1989. The MUG glucuronidase test for E. coli in

food and water. In: Turano, A. (Ed.), Rapid Methods and

Automation in Microbiology and Immunology. Brixia Academic Press, Brescia, Italy, pp. 290–308.

Havemeister, G., 1991. Determination of total coliform and faecal

coliform bacteria from bathing water with Fluorocult-Brilabroth. Acta Microbiol. Hung. 38, 257–264.

Heizmann, W., Doller, P.C., Gutbrod, B., Werner, H., 1988. Rapid

identification of E. coli by Fluorocult media and positive indole

reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 26, 2682–2684.

Huang, H., Oberkotter, E., Blume, H., 1994. Determination of E.

coli with MUG Fluorocult-lauryl sulfate broth for the testing of

microbial contamination in drugs. Pharmazie 49, 428–432.

Humbert, F., Salvat, G., Colin, P., Lahellec, C., Bennejean, G.,

1989. Rapid identification of Salmonella from poultry meat

products by using ’Mucap test’. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 8,

79–83.

Jermini, M., Domeniconi, F., Jaggli, M., 1994. Evaluation of

C-EC-agar, a modified mFC-agar for the simultaneous enumeration of faecal coliforms and E. coli in water. Lett. Appl.

Microbiol. 19, 332–335.

Kang, D.H., Fung, D.Y., 1999. Development of a medium for

differentiation between E. coli and E. coli O157:H7. J. Food

Protect. 62, 313–317.

¨

Kuhn,

H., Wonde, B., Rabsch, W., Reissbrodt, R., 1994. Evaluation of Rambach agar for detection of Salmonella Subspecies I

to VI. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60, 749–751.

Landre, J.R., Anderson, D.A., Gavriell, A.A., Lambl, A.J., 1998.

False positive coliform reaction mediated by Aeromonas in the

colilert defined substrate technology system. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 26, 352–354.

Larinkari, U., Rautio, M., 1995. Evaluation of a new dipslide with

a selective medium for the rapid detection of b-glucuronidasepositive E. coli. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 14, 606–

609.

217

Lee, J.V., Lightfoot, N.F., Tillett, H.E., 1995. An evaluation of

presence / absence tests for coliform organisms and E. coli,

International Conference on Coliforms and E. coli, Problem or

Solution?, Leeds, UK.

Ley, A.N., Barr, S., Fredenburgh, D., Taylor, M., Walker, N.,

1993. Use of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-b-D-galactopyranoside for the isolation of b-D-galactosidase-positive bacteria

from municipal water supplies. Can. J. Microbiol. 39, 821–

825.

Littel, K., Hartman, P.A., 1983. Fluorogenic selective and differential medium for isolation of faecal streptococci. Appl.

Environ. Microbiol. 45, 622–627.

Manafi, M., 1995. New medium for the simultaneous detection of

total coliforms and E. coli in water. Abstracts of the 95th

Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology. Washington, DC, Abstr.P-43, p. 389.

Manafi, M., 1996. Fluorogenic and chromogenic substrates in

culture media and identification tests. Int. J. Food Microbiol.

31, 45–58.

Manafi, M., 1998. Culture media containing fluorogenic and

chromogenic substrates. De Ware (n)-Chemicus 28, 12–17.

Manafi, M., Kneifel, W., Bascomb, S., 1991. Fluorogenic and

chromogenic substrates used in bacterial diagnostics. Microbiol. Rev. 55, 335–348.

Manafi, M., Kremsmair, B., 1999. Rapid procedure for detecting

E. coli O157:H7 in food. Abstr. P 10, pp. 513, Abstracts of the

99th Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology,

Chicago, USA.

Manafi, M., Rosmann, H., 1998. Evaluation of Readycult presence-absence test for detection of total coliforms and E. coli in

water. Abstr. Q 263, pp. 464. Abstracts of the 98th Meeting of

the American Society for Microbiology, Atlanta, USA.

Manafi, M., Windhager, K., 1997. Rapid identification of enterococci in water with a new chromogenic assay. Abstr.

P-107, pp. 453, Abstracts of the 97th Meeting of the American

Society for Microbiology, Miami, USA.

March, S.B., Ratnam, S., 1986. Sorbitol-MacConkey medium for

detection of E. coli O157:H7 associated with hemorrhagic

colitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 23, 869–872.

Messer, W., Dufour, A., 1998. A rapid, specific membrane

filtration procedure for enumeration of enterococci in recreational water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62, 3881–3884.

Mori, T., Takahashi, H., Maehata, E., Naka, H., 1991. Rapid

identification of E. coli from urine by using Fluorocult media.

Acta. Microbiol. Hung. 38, 273–281.

Moyer, N.P., 1987. Clinical significance of Aeromonas species

isolated from patients with diarrhoea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 25,

2044–2048.

Muto, T., Arai, K., Miyai, M., 1991. Evaluation of betaglucuronidase activity for the isolation of diarrhea-causing E.

coli. Kansenshogaku Zasshi 65, 687–691.

Niemi, R.M., Ahtiainen, J., 1995. Enumeration of intestinal

enterococci and interfering organismsm with Slanetz-Bartley

agar, KF streptococcus agar and the MUST method. Lett. Appl.

Microbiol. 20, 92–97.

Okrend, A.J., Rose, B.E., Lattuada, C.P., 1990. Use of 5-bromo-4chloro-3-indoxyl-b-D-glucuronide in MacConkey sorbitol agar

to aid in the isolation of E. coli O157:H7 from ground beef. J.

Food Protect. 53, 941–943.

218

M. Manafi / International Journal of Food Microbiology 60 (2000) 205 – 218

Onoue, Y., Konuma, H., Nakagawa, H., Hara-Kudo, Y., Fujita, T.,

Kumagai, S., 1999. Collaborative evaluation of detection

methods for E. coli O157:H7 from radish sprouts and ground

beef. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 46, 27–36.

Perry, D.F., Quiring, C., 1997. Fundamental aspects of enzyme /

chromogenic substrate interactions in agar media formulations

for esterase and glycosidase detection in Salmonella. In Salmonella and Salmonellosis 1997 Proceedings, Ploufragan,

France, pp. 63–70.

Perry, J.D., Ford, M., Taylor, J., Jones, A.L., Freeman, R., Gould,

F.K., 1999. ABC medium, a new chromogenic agar for the

selective isolation of Salmonella spp. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37,

766–768.

Pignato, S., Marino, A.M., Emanuelle, M.C., Iannotta, V., Caracappa, S., Giammanco, G., 1995. Evaluation of new culture media

for rapid detection and isolation of Salmonellae in foods. Appl.

Environ. Microbiol. 61, 1996–1999.

Rambach, A., 1990. New plate medium for facilitated differentiation of Salmonella spp. from Proteus spp. and other enteric

bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56, 301–303.

Restaino, L., Frampton, E.W., Irbe, R.M., Schabert, G., Spitz, H.,

1999a. Isolation and detection of Listeria monocytogenes using

fluorogenic and chromogenic substrates for phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C. J. Food Protect. 62, 244–251.

Restaino, L., Frampton, E.W., Turner, K.M., Allison, D.R., 1999b.

A chromogenic plating medium for isolating E. coli O157:H7

from beef. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 29, 26–30.

Rhodes, M.W., Kator, H., 1997. Enumeration of enterococcus sp.

using a modified mE method. J. Appl. Microbiol. 83, 120–126.

Rice, E.W., Allen, M.J., Brenner, D.J., Edberg, S.C., 1991. Assay

for b-glucuronidase in species of the genus Escherichia and its

application for drinking-water analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57, 592–593.

Schets, F.M., Medema, G.J., Havelaar, A.H., 1993. Comparison of

Colilert with Dutch standard enumeration methods for E. coli

and total Colifoms in water. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 17, 17–19.

Slanetz, L.W., Bartley, C.H., 1957. Numbers of enterococci in

water, sewage, and feces determined by the membrane filter

technique with an improved medium. J. Bacteriol. 74, 591–

595.

Stein, K.O., Bochner, B.R., 1998. Tellurite and Novobiocin

improve recovery of E. coli O157:H7 on Rainbow Agar

O157, Abstracts of the 98th Meeting of the American Society

for Microbiology, 1998, P-80.

Szabo, R.A., Todd, E.C., Jean, A., 1986. Method to isolate E. coli

O157:H7 from food. J. Food Protect. 10, 768–772.

Taormina, P.J., Clavero, M.R.S., Beuchat, L.R., 1998. Comparison

of selective agar media and enrichment broths for recovering

heat-stressed E. coli O157:H7 from ground beef. IFT’S 1998

Annual Meeting, Atlanta, USA.

Venkateswaran, K., Murakoshi, A., Satake, M., 1996. Comparison

of commercially available kits with standard methods for the

detection of coliforms and E. coli in foods. Appl. Environ.

Microbiol. 62, 2236–2243.

Wallace, J.S., Jones, K., 1996. The use of selective and differential

agars in the isolation of E. coli O157 from dairy herds. J. Appl.

Bacteriol. 81, 663–668.

Zadik, P.M., Chapman, P.A., Siddons, C.A., 1993. Use of tellurite

for the selection of verocytoxigenic E. coli O157. J. Med.

Microbiol. 39, 155–158.