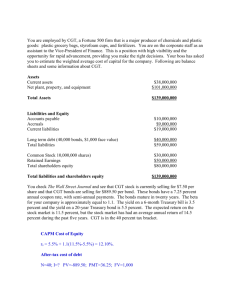

Australia Post: Consolidated Weighted Average Cost of Capital

advertisement