Federal Court of Australia - Australian Financial Review

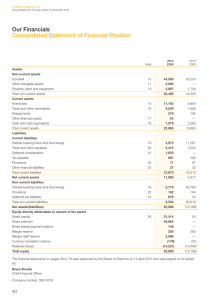

advertisement