Cohort #4 Journal - University of St. Thomas

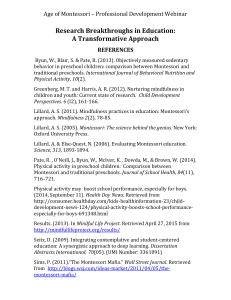

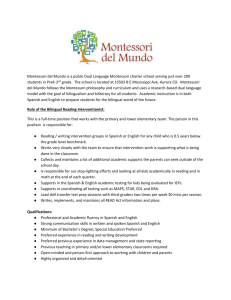

advertisement