1

Primus Automation Division, 2002

In early 2002, Tom Baumann, an analyst in the Marketing and Sales Group of the Factory

Automation Division of Primus Corporation, had to recommend to the division sales manager,

Jim Feldman, the terms under which Primus would lease one of its advanced systems to Avantjet

Corporation, a manufacturer of corporate-jet aircraft. Specifically, Baumann was weighing a

choice among four alternative sets of lease terms.

The problem of analyzing and setting lease terms was relatively new to Baumann and had

arisen only a month earlier, when Avantjet informed Baumann and Feldman that its pending

purchase of the factory-automation system had been put on indefinite hold. Avantjet’s CEO had

just ordered a moratorium on any capital expenditures that might negatively affect Avantjet’s

income statement and balance sheet. Baumann was not completely surprised by Avantjet’s

decision. Just recently, the Wall Street Journal had singled out Avantjet’s declining stock price

and worsening balance sheet as an example of manufacturers’ deteriorating condition during the

economic recession.

Only three months earlier, Baumann and Feldman had won an apparent competition for

Avantjet’s business over Primus’s leading competitors, Faulhaber Gmbh of Germany and Honshu

Heavy Industries of Japan. Baumann feared that Avantjet’s temporizing would give those two

competitors an opportunity to renew their selling efforts to Avantjet.

Feldman challenged Baumann to find a way to make the sale: “Help me salvage this deal

or we won’t make our sales budget for the year. Also, given the steep competition, we might lose

the customer altogether on future sales.” Baumann explored a range of creative financing terms,

such as leasing, that might remove Avantjet’s reluctance to proceed. He concluded that

structuring the transaction as a lease might save the deal. Now, choosing the annual lease

payment remained the only detail to be settled before returning to Avantjet with a proposal.

Primus Automation Division

Primus Automation, a division of a large, worldwide manufacturing and services firm,

was an innovative producer of world-class factory-automation products and services, with

operations in the United States, Europe, and Asia. Primus’s products included programmable

controllers, numerical controls, industrial computers, manufacturing software, factory-automation

systems, and data communication networks.

The business environment had changed dramatically over the past year. Slower

economic growth, coupled with increased competition for market share, had been forecast for the

next few years. Still, a recent resurgence in the U.S. manufacturing base – due to the weakened

dollar driving up U.S. exports – was spurring factory automation. Cross-continental industry

alliances and an accelerated rate of new product introductions had heightened industry rivalries.

Primus Automation’s objectives were to maintain leadership in market share, increase

sales by 15 percent a year, and achieve its targets for net income and working capital turnover.

Those objectives were to be realized by providing the most responsive customer service, attaining

a strong share position in the high volume-growing segments, and offering leading-technology

products based on industry standards.

Meeting the objectives required stimulating the demand by creating new incentives for

purchasing automation equipment. Many of the unsophisticated users of automation equipment

in the United States needed to be educated in analyzing capital expenditures, tax incentives, and

alternative methods for acquiring the needed equipment. Division executives had discussed

various asset-financing approaches as a means of assisting with the placement of their systems.

This case was prepared by Robert Hengelbrok, under the supervision of Robert F. Bruner and with the assistance of

Sean D. Carr. It was written as a basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate the effective or ineffective handling

of an administrative situation. Copyright © 2005 by the University of Virginia Darden School Foundation,

Charlottesville, VA. All rights reserved.

2

Asset-Financing Approaches

Baumann discussed with Primus’s division executives the variety of ways a firm might

acquire the use of a Primus Automated Factory System. First, the customer could purchase a

system with cash or with borrowed funds, either unsecured or collateralized by the equipment.

Second, the firm could acquire the equipment through a conditional sale in which the title would

pass to the firm upon the receipt of the final payment. Finally, the customer could lease the

equipment in one of two ways: (1) via a cancelable operating lease, which could carry a term that

was less than the economic life of the property; or (2) via a noncancelable financial capital lease

that would span the entire economic life of the property.

Capital versus Operating Leases

Baumann reviewed his notes on the rules defining the two types of leases. To be

classified as a capital lease under the guidelines of Financial Accounting Standards Board

(FASB) Statement No. 13,1 the lease had to meet one or more of the following four criteria:

a. Ownership of the asset transferred by the end of the lease term.

b. The lease contained a bargain-purchase option, whereby the lessee had to pay the fair

market value for the property at the end of the lease.

c. The lease term was equal to 75 percent or more of the economic life of the property.

d. The present value of the lease payments over the lease term was equal to or greater than

90 percent of the fair market value of the leased property at the beginning of the lease.

If the lease qualified as a capital lease, then the lessee would be required to depreciate the

equipment by showing it as an asset and a liability on its balance sheet. The lessee could not

deduct the lease payment from its income taxes. At the end of the lease, the lessee retained

ownership and bore the risk of early changes in the asset’s value.

If the lease met none of the foregoing criteria, it would be classified as an operating lease.

As an operating lease, the lease payments would be treated as an ordinary expense, deductible

from taxable income. The leased property would not appear on the lessee’s balance sheet and,

after the lease term, would revert to the lessor.

Primus Automation had never before offered leasing and was unfamiliar with the actual

workings of leasing arrangements. Fortunately, the Equipment Finance Division of Primus’s

parent company had extensive leasing expertise and assisted Baumann in his research. As he dug

out some of the information that the division had sent him, Baumann realized that this was the

first application of his efforts and he wanted to make sure he understood all the nuances involved

with leasing.

Avantjet

Baumann had heard that Avantjet’s vice president of operations was determined to get an

automation system to cut costs and accelerate his company’s production line. A large backlog of

orders for both new jets and the retrofitted older models had put new demands on production.

Without such a system, it would be very difficult to meet promised deliveries. In addition,

Baumann knew that Avantjet’s capital-budgeting process included all major expenditures – new

construction and capital leases – but excluded operating leases.

The risk of obsolescence and the ability to upgrade equipment weighed heavily in

Avantjet’s decision. Overall, the most important factor was cash flow, because Avantjet wanted

1

Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 13: Accounting for Leases, Financial Accounting

Standards Board (November 1976), 7-9.

2

3

to avoid any additional unplanned expenditures in 2002. Avantjet was very capital intensive and

was only marginally profitable because it was so highly leveraged. (Exhibits 1 and 2 show

Avantjet’s income statement and balance sheet)

With that in mind, Baumann wondered how he was going to find a way to resolve all the

issues. He knew that many companies had turned to leasing to address some of those concerns.

Although many of the large firms in the airframe industry were not as cash strapped as the smalland medium-sized shops, it was worthwhile to find out what classes of customers would benefit

financially from leasing. Baumann surmised that tax rates and cost-of-capital disparities between

the lessor and lessee might be critical drivers in any lease arrangement.

Primus’s Competitors

Several months earlier, when Avantjet was reviewing system proposals from Primus,

Honshu and Faulhaber, Baumann and Feldman learned from Avantjet that all three systems were

roughly equivalent but differed in pricing. Table 1 summarizes the pricing options then

available:

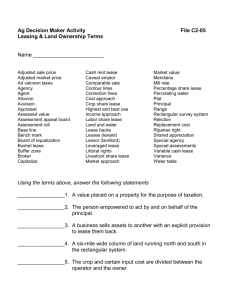

Table 1 | Summary of the available pricing options (in US$)

System Manufacturer

Faulhaber Gmbh

Honshu Heavy Industries

Primus Automation Division

Purchase Price of

System if Avantjet

Were to Buy

$805,000

$787,000

$745,000

Quoted Annual Lease Expense and

Guaranteed Residual Value2 for

5-Year Operating Lease

$160,000; 27% residual value

$158,000; 25% residual value

Not previously quoted

Baumann had learned from industry newsletters that foreign manufacturers sometimes

exploited their allegedly lower costs of capital as a competitive weapon in designing financing

terms for their customers. Baumann wondered whether this was apparent in the lease terms

proposed by Faulhaber and Honshu, and planned to estimate the effective lease costs under their

respective proposals.

Primus’s Lease Proposal

The particular deal that Feldman had called Baumann about was a proposal for a

$745,000 factory-automation system. This equipment would enable Avantjet to operate a group

of workstations from a central control site while gaining valuable feedback and planning

capabilities. Realizing that he had to find out more about Avantjet’s motives for delaying the

project, Baumann quizzed Feldman about Avantjet’s performance and requirements. Feldman

told Baumann that Avantjet’s last CEO had been replaced by a senior executive from outside the

firm who was more concerned about the bottom line and the balance sheet than he was about

making capital expenditures that had long paybacks.

With that in mind, Baumann began to assess this particular deal. The price of the total

package was $745,000. Baumann assumed that Avantjet’s primary alternative to leasing was to

borrow the purchase price of the equipment on a non-amortizing five-year loan. The Equipment

Finance Division also quoted Baumann two alternatives for a five-year operating lease with equal

annual payments (due at the beginning of each year) that varied depending on Avantjet’s actual

tax rate and cost of debt. At the end of the lease term, renewal was subject to negotiation

between the two parties. Factory-automation equipment was classified as technological

2

Residual value was the estimated fair value of a leased asset at the end of the lease term. Because future

values were difficult to predict, residual values were often highly subjective. Equipment leases typically

stipulated a guaranteed residual value.

3

4

equipment with a five-year life. Five-year MACRS3 depreciation rates, based on the full value of

the property, were as follows in Table 2:

Table 2 Five-Year MACRS

Income Tax Depreciation Rate Schedule

Year

Percentage

1

20.00

2

32.00

3

19.20

4

11.52

5

11.52

In order to structure it as an operating lease, the Equipment Finance Division required an

20.2729 percent residual guarantee from Baumann’s division. Baumann did not know how

sensitive to the residual assumption the results would be. Because his division was trying to

move into leasing to bolster sales, he figured that it might be willing to assume some of the risk of

the equipment’s value declining substantially in five years. Primus Automation might also have

to assist the Equipment Finance Division in remarketing the equipment to another user, if a new

lease were not signed when the original lease expired. (Exhibit 3 lists the various pricing and

leasing terms)

EXHIBIT 1 | Avantjet’s Statement of Income ($000’s)

2001

$576,327

9,985

586,312

2000

$575,477

6,976

582,453

1999

$432,522

9,677

442,199

425,076

43,624

13,773

84,062

423,443

36,215

12,873

87,259

325,016

35,632

9,064

27,002

566,535

559,790

396,714

Income before taxes

Taxes

19,777

6,724

22,662

7,705

45,485

15,465

Net income

13,053

14,957

30,020

Sales

Other income

Gross income

Cost of good sold

Selling, general & admin.

Research & development

Interest

Total expenses

Source: Company records.

3

MACRS stood for modified accelerated cost recovery system. It was a method of accelerated

depreciation allowed under the U.S. Tax Code. Under MACRS, depreciation deductions were determined

without regard to the asset’s residual value. The terminal loss or gain will be directly incorporated into firm

profit/loss. To compare with the Canadian tax code, this is identical to the assumption that the asset pool is

terminated at the end of the lease term.

4

5

EXHIBIT 2 Avantject's Balance Sheet ($000)

2001

2000

$19,918

37,791

310,180

13,928

381,817

$27,263

37,307

323,101

13,362

401,033

2,245

30,654

26,932

1,683

1,668

63,182

12,634

50,548

640,369

$1,072,734

2,245

30,229

21,244

1,520

885

56,123

8,267

47,856

648,339

$1,097,228

$592

42,355

4,750

$563

38,760

5,760

39,627

146,964

234,288

43,855

160,946

249,888

646,633

42,661

689,294

671,255

41,498

712,723

3,385

74,081

72,017

-331

149,152

$1,072,734

3,027

69,770

62,156

-336

134,617

$1,097,228

Assets

Current assets:

Cash and temporary investments

Accounts receivable

Inventories

Prepaid expenses

Total current assets

Property, plant, and equipment:

Land

Buildings

Machinery and equipment

Furniture and fixtures

Construction in progress

Less accumulated depreciation

Net property, plant, and equipment

Other assets

Total assets

Liabilities and stockholders' equity

Current liabilities:

Long-term debt

Accounts payable

Notes payable

Accrued compensation, interest,

and other liabilites

Deposits and progress payments

Total currect liabilities

Long-term nots payable to banks

Deferred income taxes

Common Stockholders' equity:

Common stock

Capital in excess of par value

Retained earnings

Less common stock in treasury

Total stockholders' equity

Total Liabilities and stockeholders' equity

Source: Company records

5

6

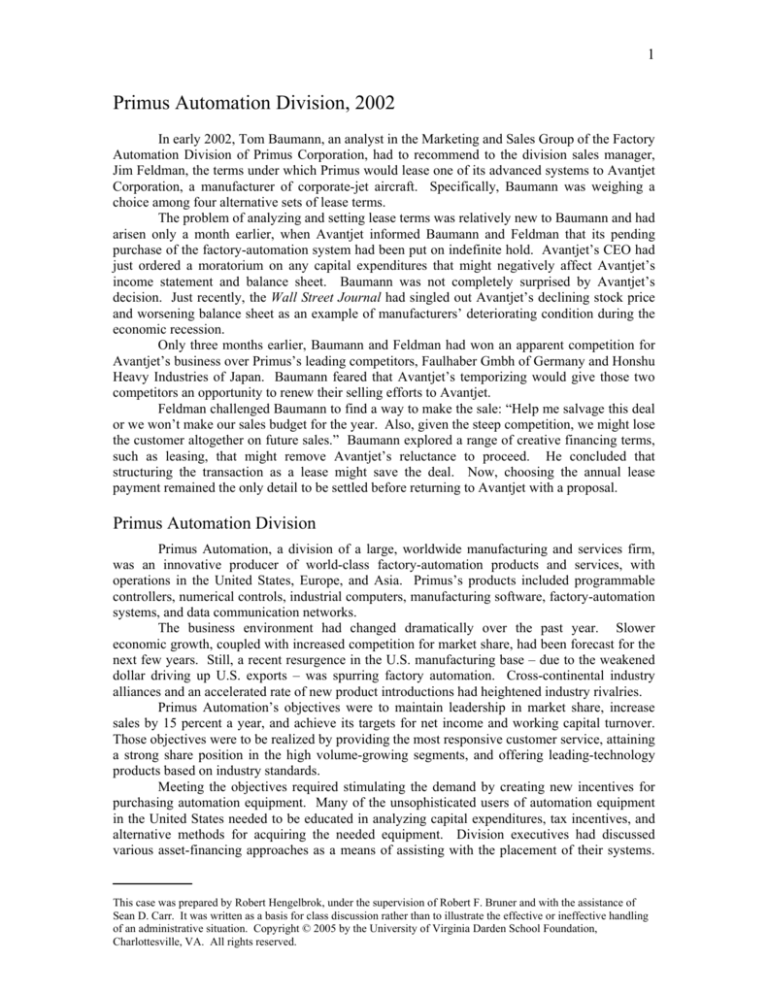

EXHIBIT 3 Terms under Hypothetical Leasing and Borrow-and-Buy

Strategies

Loan ("Borrow-and-Buy")

5-year term loan

Payment in arrears

Equipment cost

Cash Down Payment

Loan amount

Lease

5-year net lease

Leasing option #1

Leasing option #2

Both Methods

Guaranteed residual value:

(required by Primus Equipment Finance Division)

Investment tax credit

Depreciation

$745,000

$0

$745,000

Annual payments

(in advance)

$150,003

$152,350

20.2729%

0%

Five-year MACRS

Issues to be addressed:

Tom Bauman needs to prepare a report to his manager, Jim Feldman. In this report, he

will clarify the following issues:

1. Compare the advantages and disadvantages of operating lease for Avantjet relative to

other alternatives including (1) borrow-and-buy, and (2) capital lease.

2. Prepare a projected balance sheet and income statement for Avantjet in year 2002 after

the first lease payment under leasing option #2, assuming that everything else remain the

same as in year 2001. Repeat the same exercise supposing that the lease is structured as a

capital lease by including a bargain purchase option, which requires Avantjet to purchase

the equipment at $60,000 by the end of the fifth year. Assume no taxation and Avantject

had about the same borrowing cost as Primus (about 9.5 percent). Show your calculation

and journal entries in appendix. Persuade Jim Feldman that given Avantjet’s situation,

operating lease is a preferred choice.

3. Assume no taxation, calculate the minimum lease payment acceptable to Primus.

Assume Avantject had about the same borrowing cost as Primus (about 9.5 percent).

4. Estimate the effective tax rate of Avanjet from the past three years' income statements.

Assume Avantjet had about the same borrowing cost as Primus (about 9.5 percent). At

the current point, Primus has a tax rate of 40%. This tax rate is estimated to last in the

next couple of years.

4.1 In exhibit 3, there are two leasing options. Evaluate the economic feasibility of

these two options based on the tax rates and interest rate provided above.

6

7

4.2 Compare Primus’ leasing option #1 with the competing offers from Faulhaber

Gmbh and Honshu Heavy Industries (See table 1). Comment on the competitiveness of

Primus.

4.3 What is the minimum lease payment acceptable to Primus? Compare the minimum

lease payment in this context with the minimum lease payment you derived from the

above (issue 3). Comment on the taxation effect.

4.4 What’s the maximum lease payment acceptable to Avantjet?

5. Small- and medium-size firms probably paid higher interest rates than Primus and

could save money if Primus financed the equipment and passed on some of the financing

savings to them. Based on Avantjet’s income statement and balance sheet, Bauman is

able to estimate the interest rate for Avantjet. He noticed that the interest rate for Avantjet

is indeed higher.

5.1 What is the minimum lease payment acceptable to Primus now?

5.2 What is the maximum lease payment acceptable to Avantjet now?

5.3 Since 2005 regulators have been concerned that the all-or-nothing capitalization

method of the current standards on leases results in off-balance sheet financing. They are

specifically critical of its rules- vs. principles-based approach, the 75% economic life and

90% fair value tests, and the complexity of the statement. The regulatory bodies feel that

material operating leases must be capitalized to show a truer picture of the lessee's

financial position. One suggested approach to accounting for leases is the asset and

liability approach which suggests that the lessee capitalize all material leases at the value

of the lessee's rights and obligations under the lease. How would this new approach, if

instituted, impact Bauman’s recommendation to Avantjet?

5.4 With a variety of options and scenarios to propose to Avantjet, Baumann believed

that Primus had a good chance of resurrecting the deal and meeting its sales goals for

2002. Persuade Jim that he is right.

6. Combining your knowledge in both accounting and finance, what factors do you think

determine whether or not a firm should engage in leasing? Apply this knowledge to

Primus and Avantjet.

7

8

Instruction: Prepare a report, according to the expectations of the case.

INTEGRATIVE CASE REPORT EXPECTATIONS

The Goals

The integrative case is a project of the instructors of Managerial Finance II (AFM 371/372) and

Intermediate Financial Accounting II (AFM 391). The case is a multi-subject case that has the

following objectives:

to encourage integration of materials from these two subject areas,

to encourage the development of case analysis skills,

to use a variety of information sources to solve an accounting problem, and

to reinforce the development of report writing skills.

The total mark of the case project includes two components: the report and the peer evaluation

based on the individual contribution for the report. The total mark will count for 10% towards the

final grades in AFM 371/372 and AFM 391 respectively, or equivalently, a combined 20% for

two courses. Out of the combined 20%, the report will receive 17% for which each group member

receives same mark, and the peer evaluation will receive the rest 3%.

Logistics

Do not contact any representative of the company. Only use publicly available information.

Due Date

The final report is due at 5:00 p.m., Thursday, November 20, 2008. It can be placed in the gray

drop box outside HH290. A 10% penalty will be levied for each day that the assignment is late,

no exceptions or excuses.

Report Expectations

Formal Expectations

1. The case is designed to integrate the topics from within, and across, the two courses. Your

analysis and report should demonstrate an integration of these concepts. Your report should

identify key issues and analyze these to arrive at a reasonable, well thought out solution.

State clearly both quantitative and qualitative recommendations that you make.

2. Your report must meet the standards of professional report writing, as taught in your English

class. Your writing must be clear, concise and free of grammatical or spelling errors.

3. Your report should be appropriate to the audience specified in the requirements of the case.

8

9

4. You can work in a group not exceeding four members. You cannot discuss the case with

anyone other than your own group members. You are bound by the ethical standards of the

university, as summarized in the course outlines of the accounting courses.

Technical Requirements

1. The main text of the report should be typed on 8” x 11” paper, double-spaced with 1”

margins on all four borders, typed with a Times New Roman font size no smaller than 11

point (i.e. this size). The main text of your report (not including the cover page, executive

summary, the table of contents, and the reference page) will be no more than eight pages.

2. Appendices, spreadsheets, exhibits and tables should not exceed an additional eight pages.

3. The report should also include a title page and a one page executive summary. The summary

should summarize the key points in your analysis and your recommendations. It should not

describe what will be found in the report, but rather summarize the contents of the report.

4. Submit only one copy of the report.

Evaluation Criteria

1. As in prior accounting and finance courses, content is particularly important. In this setting,

thoroughness and thoughtfulness of the analysis are the key components of content. Do not

simply perform a superficial analysis of the issues; rather attempt to understand the issues at a

greater depth. Review course material to determine the relevant knowledge and analyses and

try to think beyond the obvious facts and figures presented in the case materials.

2. Integration of materials will also be rewarded.

3. Recommendations should be clear and supported by the analysis performed.

Style is also important. Take on the role given and write to the audience specified.

Other Guidance and “Tips”

1. Determine the primary thrust of your report before you begin to write. Compose the report

such that everything contributes to this primary thrust. Plan your structure to achieve your

goals.

2. This is a business report. Be very careful to write to a relatively sophisticated business

reader.

3. Pay close attention to how material is presented in graphs and tables. Each such exhibit

should be completely self-explanatory with clear and accurate labels. Looking only at the

exhibit alone, can its message be clearly understood?

4. If you wish to cite outside materials (other than those provided directly to you), be selective

in how you cite these – this is a business report, not an academic essay. The case is designed

such that significant additional outside materials are not necessary to complete the analysis.

9