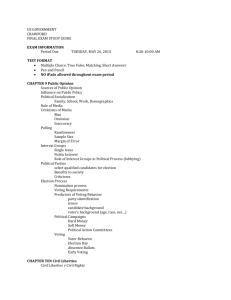

Due Process and the Concept of Ordered Liberty

advertisement