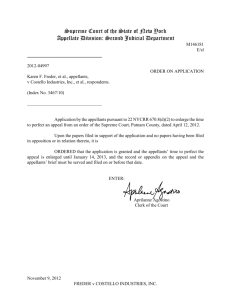

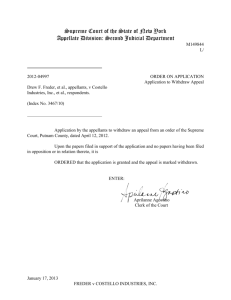

Cambridge University Press, et al. v. Becker, et al.: Appellant

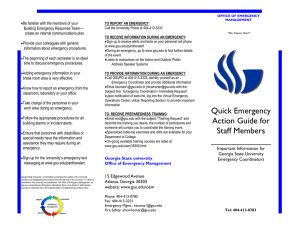

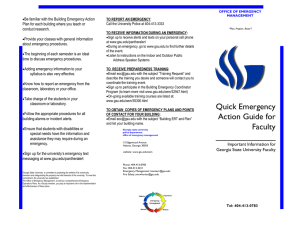

advertisement