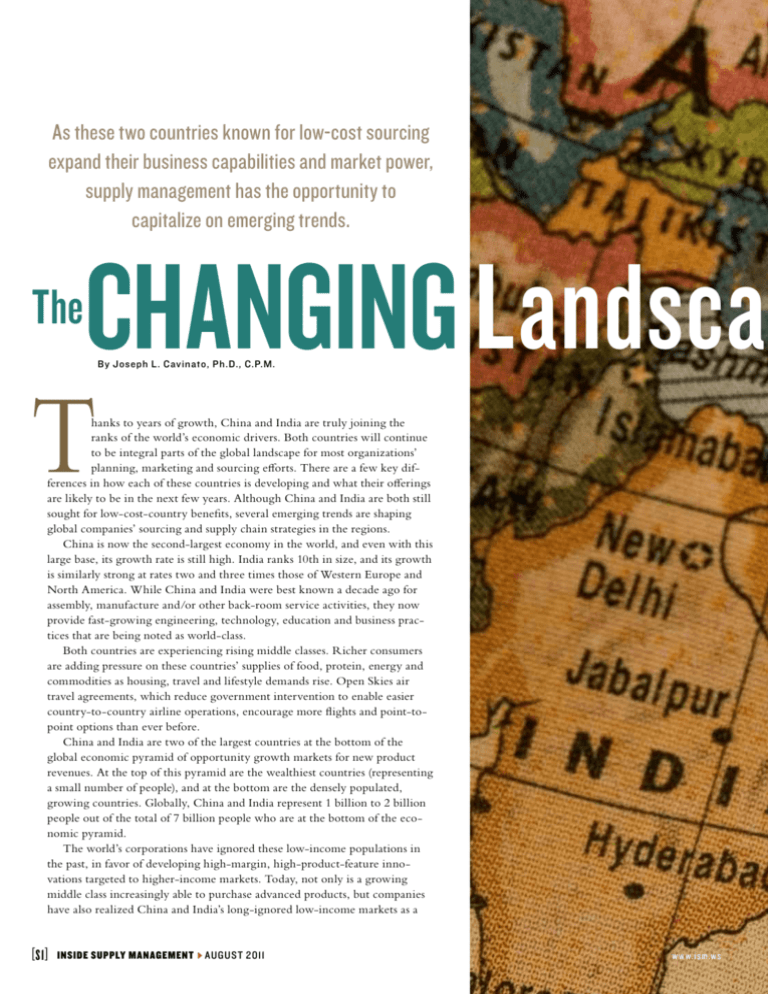

As these two countries known for low-cost sourcing

expand their business capabilities and market power,

supply management has the opportunity to

capitalize on emerging trends.

The

Changing Landsca

T

By Joseph L. Cavinato, Ph.D., C.P.M.

hanks to years of growth, China and India are truly joining the

ranks of the world’s economic drivers. Both countries will continue

to be integral parts of the global landscape for most organizations’

planning, marketing and sourcing efforts. There are a few key differences in how each of these countries is developing and what their offerings

are likely to be in the next few years. Although China and India are both still

sought for low-cost-country benefits, several emerging trends are shaping

global companies’ sourcing and supply chain strategies in the regions.

China is now the second-largest economy in the world, and even with this

large base, its growth rate is still high. India ranks 10th in size, and its growth

is similarly strong at rates two and three times those of Western Europe and

North America. While China and India were best known a decade ago for

assembly, manufacture and/or other back-room service activities, they now

provide fast-growing engineering, technology, education and business practices that are being noted as world-class.

Both countries are experiencing rising middle classes. Richer consumers

are adding pressure on these countries’ supplies of food, protein, energy and

commodities as housing, travel and lifestyle demands rise. Open Skies air

travel agreements, which reduce government intervention to enable easier

country-to-country airline operations, encourage more flights and point-topoint options than ever before.

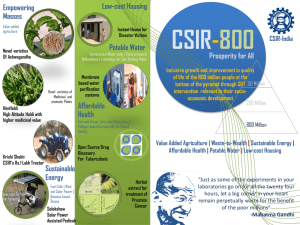

China and India are two of the largest countries at the bottom of the

global economic pyramid of opportunity growth markets for new product

revenues. At the top of this pyramid are the wealthiest countries (representing

a small number of people), and at the bottom are the densely populated,

growing countries. Globally, China and India represent 1 billion to 2 billion

people out of the total of 7 billion people who are at the bottom of the economic pyramid.

The world’s corporations have ignored these low-income populations in

the past, in favor of developing high-margin, high-product-feature innovations targeted to higher-income markets. Today, not only is a growing

middle class increasingly able to purchase advanced products, but companies

have also realized China and India’s long-ignored low-income markets as a

[ S1 ]

Inside supply management

August 2011

www.ism.ws

pes of

China and India

www.ism.ws

August 2011 Inside supply management

[ S2 ]

The

Changing Landscapes of China and India

vast marketplace of people who will

purchase low-cost/priced and lowfeature products. For example, simple

cell phones designed to only send and

receive calls are being rolled out at

affordable prices, and while the margins

are low, this market has high-volume

potential.

Both countries are experiencing

fast-rising technology and innovation

value chains. For instance, China has

long been ideal for low-cost manufacturing, and India was known for

IT and customer-support outsourcing

opportunities, but the lines are beginning to blur between countries. China

has been moving into some services

areas and building a strong base of

English speakers, catching up on India’s

long-standing language advantage.

Indian companies are actively seeking

of the yuan continues to increase, which

is beginning to spur national inflation.

The rush is now westward and southward to locales farther from the coast

but closer to cheaper labor. This migration can be seen in the Guangdong

province along the coast, which is now

reported to have more than 10,000

empty factory buildings.

The centers of gravity for entire

industries are shifting, with two of the

most prominent being the cell phone

and computer assembly industries; this

industrial migration took place at a

faster rate than economists predicted it

would just 10 years ago. Additionally,

many Chinese companies are looking

farther to outsource or operate in

Laos, Cambodia, Myanmar and other

lower-cost countries. This means that

developed-market companies concerned

There is no one established business model that can

be exported from developed countries to China or India

and be expected to work.

manufacturing business opportunities.

The playing field for both countries is

leveling, and in the coming decade we

can expect to see business capabilities

grow more sophisticated as these markets expand.

China: An Evolving National

Landscape

Traditional growth in China

occurred along the coastal regions of

the country. These were the areas with

easy world-outlet access through the

ports of Hong Kong and Shanghai.

Today, manufacturing is quickly

spreading inland among the country’s

22 provinces. According to a June

2011 study by The Boston Consulting

Group, Chinese wages are rising at

about 17 percent per year and the value

[ S3 ]

Inside supply management

August 2011

about supply chains five, six and seven

tiers deep are facing more complex

challenges to track and assure quality

and other product attributes.

China is quickly mimicking the

United States’ industrial origins by

moving rapidly up the value chains of

most industries. With higher education

and access to technologies and investments, low-cost labor is beginning to

shift to companies that manufacture

brand products, from research and

product development stages through

the life cycle of the products.

Chinese consumer electronics and

home appliances manufacturer Haier

has done this successfully with its products in North America and Western

Europe. Supported by recent growing

demand for automobile and car-part

manufacturing built by U.S. and

European marketrs, China is poised to

become a major brand player in world

automobile brands. The next target for

the country is to do the same in commercial aircraft development and sales.

In the midst of these developments,

challenges still remain regarding honoring intellectual property. Clarity,

enforcement and resolution of intellectual property issues are often

complicated by a vast mosaic of laws,

regulations and courts at local, provincial and national levels. Quality

issues and material substitutions can

be common, thanks to a long-heldover culture in some areas from the

Communist era, focusing on producing

target output numbers above all else.

As a result, major supplier oversight

and assurance efforts are necessary in

most industries. Today, many Chinese

companies seek to improve quality and

supplier performance to gain an edge in

their quests for growth in global markets, and look to foreign companies for

customer training and supplier development methods and models.

China has also been making significant improvements to its physical

attributes as well as its business acumen.

It is the first country in almost a

hundred years to plan, invest in and

build its infrastructure in advance of

economic growth. The United States

was the only other country to do this,

beginning in the 1880s through to the

completion of the interstate highway

system in the 1970s. Most other countries experience growth first, and then

have to invest after the fact to address

the accompanying capacity shortages

of highways, airports, electricity production and more. These countries,

and their industries and societies, are

frequently saddled with higher financial

and social costs. China, on the other

hand, has been forward-looking with

its infrastructure investments, and these

improvements act to continually lower

the overall costs of manufacturing and

costs of living. This is the country’s significant competitive advantage and one

that will give it an economic edge for

many decades to come.

www.ism.ws

India: Rapid Economic

Development

India has had one early edge in

developing its outward global growth:

mastery of the English language. Each

of India’s 28 states has separate dominant

languages, but English is common across

all. Thanks largely to India’s ability to

communicate in the world’s primary

business language, its economy has

been growing at high rates in the last

two decades, and it is now the world’s

10th largest economy according to the

International Monetary Fund’s 2011

Report for Selected Countries and Subjects.

The global chase for low labor costs

focuses on India’s national technical

educational levels, development of

technologies and lower costs of readily

available global communication links.

These characteristics have given it a

worldwide edge in high-end corporate

services. Today, technologies comprise

approximately 55 percent to 60 percent

of its GDP, and this will continue to

spur enhancements in education, attraction of talent and market opportunities

for India’s businesses.

A gradual opening of retail market

participation by outside companies is

taking place in India. Long-standing

consumer product companies like

Hindustan Lever (of Unilever) have

an edge because they understand the

uniqueness of this market and the complexity of its distribution and marketing.

Bureaucracy and a wide range of

regulations are major challenges in

India. In many of its states, organizations employing 100 or more employees

that need to downsize may not lay off

employees without government permission, according to the Industrial

Disputes Act. This restriction has

generally discouraged U.S.-based companies from entering into the country

with green investment projects; instead,

companies prefer to use and develop

locally owned and operated manufacturing capacity.

In terms of infrastructure, a major

highway project is under way called

the Golden Quadrilateral, and it should

speed and lower costs of truck transportation connecting New Delhi,

Mumbai, Chennai and Kolkata. ABM

Trans-Lines Shipping and Logistics

Corporation privately operates a port

in the country, and it is widely considered to be very efficient. As Singapore

recognized many years ago, world-class

airports attract and encourage business

activity and investment. India recently

opened a US$2.2 billion world-class

terminal at the international airport in

New Delhi.

Though India is now experiencing

inflation between 8 percent and 9 percent (reported at 8.72 percent in May

2011), it will long be a viable source of

quality manufacturing at low costs as

well as a possible market for expansion.

Like China, it has the advantages of

both first- and third-world economies

all in one, meaning companies have

the opportunity to competitively sell

high-end products to richer consumers

in these countries, and sell less elaborate

products to the rest of the economic

market, as well.

The Next Horizons

There are few general statements

that can be made about the trends in

these two countries. China will not

be the only low-cost manufacturing

resource, nor India the only high-tech,

low-cost resource of the near future.

Leaders in both countries understand

the need to branch out and provide

their low-cost advantages by looking at

outsourcing options in other countries.

Both countries’ growth and middle

classes will expand their automobile

industries, bringing the attendant high

employment, development of engineering, expertise in global marketing

and further increase in foreign earnings. These new automotive-related

companies will no doubt grow into

global corporations in their own rights,

and compete with the established U.S.,

Japanese and Western European companies. As new and growing industries in

their local markets, they will have the

advantage of being able to concentrate

on new paradigms and new technologies

in the industry — a level of flexibility

not always possible for the legacy companies in established developed markets.

There is no single established business model that can be exported from

developed countries to China or India

and be expected to work. Each country’s legal system, history, culture,

markets and more require fine-tuning

regarding how companies operate,

create strategic directions, make decisions and so on. Supply management

professionals in the 1980s who were

some of the first to travel and look at

working in or outsourcing to China

and/or India were the first to understand this. The nuances — and benefits

— of working in different countries are

why outsourcing, collaboration and the

use of many forms of third-party organizations is so common today and will

continue to be in the future. It is why

supply chains are longer and more complex, and must be able to quickly morph

into different forms today based on

global market demands and limitations.

More than anything, the growth and

future directions of China and India

point to the simple fact that low-cost

labor is not the only big driver in globalization today. Low-cost labor now

shifts geographies in as few as five years.

Instead, successful globalization of

sources, as well as product and services

sourcing, requires constant balance and

flexibility in total costs of labor, currency levels, interest rates, technology

and skills bases, costs of capital in the

supply chain from factory to consumer,

and energy costs. In fact, as environmental concerns become boardroom

and stockholder priorities, we may just

be entering a new era where the costs

of energy will be the major driver of

where we source our production.

Supply management professionals

competent in the subtleties and necessary flexibilities inherent in doing business on a global scale will be able to face

these challenges effectively, no matter

where in the world they are doing

business. ISM

Joseph L. Cavinato, Ph.D., C.P.M. is ISM professor of supply chain

management at Thunderbird School of Global Management in

Glendale, Arizona, and director, A.T. Kearney Center for Strategic

Supply Leadership at ISM in Tempe, Arizona. For more information,

send an e-mail to author@ism.ws.

© Institute for Supply Management ™. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission from the publisher, the Institute for Supply Management™.

www.ism.ws

August 2011 Inside supply management

[ S4 ]