Drunk Driving: Seeking Additional Solutions

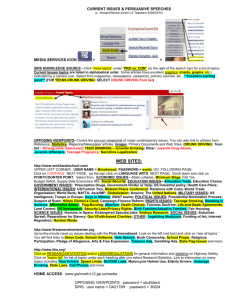

advertisement