PDF - Centre for Contemporary Canadian Art

advertisement

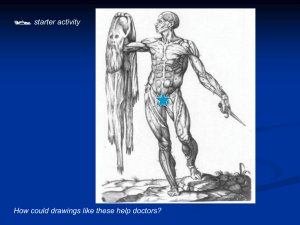

DISSECTION/FRAGMENTATION: THE FEMALE ANATOMICAL BODY IN THE WORK OF JEANNIE THIB AND CATHERINE HEARD THROUGH THE VESALIAN TROPE OF DE HUMANI CORPORIS FABRICA LIBRI SEPTEM Amanda Brownridge “The fragment – incomplete, detached, isolated – is of an uncertain signifying power. Potentially little more than detritus, it can also possess extraordinarily resonant dimensions: the glimpse of memory, the residue of history, the power of metaphor.”1 Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564), a Flemish anatomist and physician, has often been called the father of modern anatomy, having published in 1543 one of the most important founding texts in the field. His magnum opus, De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem, aimed to challenge traditions that had long been entrenched in the practice; that of basing knowledge of the human body on the dissection of animals and notably the theories of Claudius Galen (AD 129 - c. 200). Vesalius presented his understanding of the human body in a way that was particularly creative and it is for this reason that the images found within the Fabrica can be studied in both the realms of science and art. Through an analysis of the illustrations found primarily in books II and V of Andreas Vesalius’ Fabrica, one observes a certain theatrical quality. It is interesting to question Vesalius’ use of theatricality and examine how and why it was applied to anatomical illustration. The images on the one hand emphasize Vesalius’ use of human dissections in his search for knowledge. While showcasing the structure and functioning of the human body in a significantly detailed manner, the illustrations simultaneously camouflage the grotesque nature of these dissections through the application of artistic traditions, notably those of classical sculpture.2 This technique of camouflage is further emphasized by the placement of his “subjects” within pastoral landscapes.3 The dual nature of these prints helps to protect the work from critique; Vesalius could not be ARTH 648B-2 Envisioning Digital and Virtual Forms of Exhibitions: The Curatorial Translation of Theory into Practice, 2012 reprimanded for representing dead bodies, as his subjects seem very much alive. At the time of Vesalius' publication, the act of dissecting human bodies was frowned upon, and in some circumstances, it considered illegal. Vesalius was often forced to dissect the bodies of executed criminals, or even dig up fresh graves in order to procure cadavers for his scientific investigations. The sculptural references in these images are related to the Canon of Polykleitos through their use of ideal mathematical proportions and the technique of Contrapposto, as well as pastoral landscapes represented as panoramas of rolling hills, distant villages, meadows and trees. 4 These elements were central to Vesalius’ publication and allowed for the creation of a performance space in which he was able to stage his thoughts on the functioning of the human body. In his quest for truth, Vesalius went to great lengths to completely dissect, classify and organize the body according to various parts or sections. Observing minute details, he was able to construct a more accurate, nuanced understanding of the whole. This concept is interesting when examined in conjunction with the work of two contemporary Canadian artists, Jeannie Thib (b. 1955) and Catherine Heard (b. 1966). Both artists appropriate the notion of dissection into their artistic production and incorporate traditions of anatomical illustration, in particular Vesalius' fragmentary view of the body. This allows for a microcosmic analysis with macrocosmic intent, as a way of situating the self within a larger historical narrative. The approach of fragmentation as a method of artistic representation thus functions like scientific dissection. This exhibition investigates the correlations between the types of images found within Vesalius’s publication and the works of Jeannie Thib and Catherine Heard. ARTH 648B-2 Envisioning Digital and Virtual Forms of Exhibitions: The Curatorial Translation of Theory into Practice, 2012 Andreas Vesalius Plate 27: Book 2, 1543 De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem Saunders, J. and O’Malley, C. The Illustrations from the Works of Andreas Vesalius of Brussels: with Annotations and Translations, a Discussion of the Plates and their Background, Authorship and Influence, and a Biographical Sketch of Vesalius. New York: Classics of Medicine Library, 1993. Andreas Vesalius (Detail) Plate 57: Book 5, 1543 De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem Saunders, J. and O’Malley, C. The Illustrations from the Works of Andreas Vesalius... ARTH 648B-2 Envisioning Digital and Virtual Forms of Exhibitions: The Curatorial Translation of Theory into Practice, 2012 Jeannie Thib Terra Incognita (I), 1993 Linocut on mulberry paper, ink 250 x 200 cm http://ccca.concordia.ca/artists/work_detail.html?languagePref=en&mkey=64658&title=Terra+I ncognita+%28l%29&artist=Jeannie+Thib&link_id=956 ARTH 648B-2 Envisioning Digital and Virtual Forms of Exhibitions: The Curatorial Translation of Theory into Practice, 2012 Terra Incognita (I) (1993) is a linocut printed on eight sheets of mulberry paper that have been pieced together to form an almost life sized image of a black silhouette of a female body. An imagined representation of the human nervous system is depicted in white on the black silhouette, while drawings of imagined organs hover around the woman. A scientific legend attempting to relate the organs to the body falls short in doing so as letters seem to match up with numbers in a completely incoherent fashion. The forms used to describe human organs have been appropriated by Thib from anatomical illustrations from a time when human dissection was forbidden, and thus medical treatises of the sort were based on an assumed knowledge, or the dissection of animals. The combination of appropriating images that represent an imagined view of the body with a system of classification that cannot function as such results in a fragmented understanding and representation of the body. This image is representational of the type of model that Vesalius aimed to rectify in his publication, one that bases its knowledge of the body on what one expects to see, and not what one has actually encountered through proper scientific investigation, and therefore dissection. In this image, the notion of fragmentation/dissection can be understood in a twofold manner. First by demonstrating that fragmentation may be representative of a lack of knowledge or information, but also as a starting point for investigation, be that scientific or artistic.5 ARTH 648B-2 Envisioning Digital and Virtual Forms of Exhibitions: The Curatorial Translation of Theory into Practice, 2012 Jeannie Thib Augur, 1997 Screen print on wooden panels, paint, ink 16 panels, each: 61 x 61 x 7cm http://ccca.concordia.ca/artists/work_detail.html?languagePref=en&mkey=64676&title=Augur& artist=Jeannie+Thib&link_id=956 ARTH 648B-2 Envisioning Digital and Virtual Forms of Exhibitions: The Curatorial Translation of Theory into Practice, 2012 Andreas Vesalius (Detail) Plate 57: Book 5, 1543 De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem Saunders, J. and O’Malley, C. The Illustrations from the Works of Andreas... ARTH 648B-2 Envisioning Digital and Virtual Forms of Exhibitions: The Curatorial Translation of Theory into Practice, 2012 In contrast with Terra Incognita, which focuses on the full female body and its anatomical parts, Augur (1997) is made up of sixteen wood panels, each an individual image of an intestine. Interestingly, the word “augur” means to predict or foretell events based on the interpretation of sign or omens, as was often used in the ancient practice of reading the future in the entrails of sacrificial animals. Each print has been centrally positioned on the panel, and displayed in two rows of eight to emphasize symmetry and balance. The pictures of the intestines are based on a variety of medical treatises, such as medieval manuscripts, Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks and even contemporary western medical texts. Thib has drawn patterns, text and diagrams into each intestine, resulting in an intricate image to be studied carefully, thus counteracting the more common reaction of repulsion in viewing such grotesque images. Augur can be seen as a direct link to the images found in book V of Vesalius’ publication which are camouflaged in the techniques of classical sculpture as a way of sanitizing them so that they could disperse scientific information in a way that does not upset the viewer.6 ARTH 648B-2 Envisioning Digital and Virtual Forms of Exhibitions: The Curatorial Translation of Theory into Practice, 2012 Jeannie Thib Tabula, 1993 Linocut on kozo paper, ink 5 sheets, each: 122 x 91cm http://ccca.concordia.ca/artists/work_detail.html?languagePref=en&mkey=64660&title=Tabula &artist=Jeannie+Thib&link_id=956 ARTH 648B-2 Envisioning Digital and Virtual Forms of Exhibitions: The Curatorial Translation of Theory into Practice, 2012 Tabula (1993) is made up of five linocut prints, each depicting the artist’s left palm in five similar positions. These hands are fragments removed from any sort of context with the body and as such, function as blank pages (like a tabula rasa) on which the artist is free to present new information. Each palm has been inscribed with various patterns and words from garden designs, maps, wilderness survival guides and body decorations. All of these elements draw on systems relating to techniques of mapping, patterning or coding to associate the relationship between humans and nature. The viewer does not know where these words or patterns come from, or what they mean in reference to each other. In this sense, Tabula can be seen as the epitome of a fragmentary view of the body; presenting un-contextualized information, leaving the viewer to contemplate their meaning or transfer their own understanding and prior knowledge onto them as a way of interpretation. This can be compared to what Vesalius aimed to achieve in his publication. Through dissection and fragmentation, Vesalius' objective was to strip the body down to the smallest detail to observe individual segments and thus better understood the entire bodily system. Tabula does just that; by representing the left hand, the artist is free to inscribe information about this part, in relation to the gestalt of humanity and nature.7 ARTH 648B-2 Envisioning Digital and Virtual Forms of Exhibitions: The Curatorial Translation of Theory into Practice, 2012 Catherine Heard Untitled (after Vesalius, 1543), 1993 Human hair, cotton, wood frames, brass plaque 165.1 x 63.5 x 48.2 cm http://ccca.concordia.ca/artists/work_detail.html?languagePref=en&mkey=22166&title=Untitled &artist=Catherine+Heard&link_id=1922 ARTH 648B-2 Envisioning Digital and Virtual Forms of Exhibitions: The Curatorial Translation of Theory into Practice, 2012 Andreas Vesalius (Detail) Plate 57: Book 5, 1543 De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem Saunders, J. and O’Malley, C. The Illustrations from the Works of Andreas... Untitled (After Vesalius, 1543) by Catherine Heard is the central panel from the triptych, Untitled (After Vidius, 1611; After Bartisch, 1575; After Vesalius, 1543). Each panel depicts male or female genitalia from three medical treatises. The panels are mounted on large stands, so that the artwork mimics how a diagram or model is displayed in a scientific context such as a laboratory or classroom. Each image has been stitched on cotton with human hair and stretched ARTH 648B-2 Envisioning Digital and Virtual Forms of Exhibitions: The Curatorial Translation of Theory into Practice, 2012 within a wooden frame. When viewed from the side, one sees the excess hair that has been left to hang in strands on the opposite side of the image as a result of the stitching. The central panel is of particular interest in this context, as it replicates an image from Vesalius’ Fabrica; that of a partially dissected penis from plate 57 in book II of the Fabrica. Catherine Heard Untitled, 1993 Human hair embroidered on silk panel 88.9 x 304.8 cm http://ccca.concordia.ca/artists/work_detail.html?languagePref=en&mkey=22163&title=Untitled &artist=Catherine+Heard&link_id=1922 ARTH 648B-2 Envisioning Digital and Virtual Forms of Exhibitions: The Curatorial Translation of Theory into Practice, 2012 Andreas Vesalius (Detail) Plate 61: Book 5, 1543 De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem Saunders, J. and O’Malley, C. The Illustrations from the Works of Andreas Vesalius... ARTH 648B-2 Envisioning Digital and Virtual Forms of Exhibitions: The Curatorial Translation of Theory into Practice, 2012 Andreas Vesalius (Detail) Plate 42: Book 5, 1543 De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem Saunders, J. and O’Malley, C. The Illustrations from the Works of Andreas... ARTH 648B-2 Envisioning Digital and Virtual Forms of Exhibitions: The Curatorial Translation of Theory into Practice, 2012 This untitled piece by Catherine Heard depicts a pregnant woman’s stomach with an incision that seems to have been labelled in the manner of a medical diagram. Below the stomach various surgical tools have been represented, along with scrolls and what can be understood as textual material on parchment paper. The images have been stitched using human hair onto a silk panel that has been hung from the ceiling and displayed so that the stitching casts a shadow of the image onto the wall behind it. A comparison can be made to the images found in book II of Vesalius’ Fabrica, as he too represents a dissection of a female womb and goes so far as to dissect the embryo, representing a step by step unveiling of the fetus. Vesalius also includes an illustration of his surgical tools in Book II, tools of his trade necessary for his investigation. In drawing on the types of images found within the Fabrica, Heard’s works contribute to the ongoing dialogue about the form and function of the human body. However, by including human hair in the equation, both in this piece and the previous one, Heard puts the “bodily” back into these representations. The tradition of depersonalizing images in its anatomical sense as practiced by Vesalius is being challenged here. Thus, this exhibition comes full circle. I began by analyzing the need to sanitize these anatomical images with Vesalius. Then I considered the work of Jeannie Thib where fragmentation is used to presenting the body as a blank canvas with information inscribed to inspire the viewer to actively engage in the search for holistic meaning. I end with the work of Heard, where the “bodily” is brought back into the art of anatomical illustration. ARTH 648B-2 Envisioning Digital and Virtual Forms of Exhibitions: The Curatorial Translation of Theory into Practice, 2012 NOTES 1 Renee Baert, “Signatures on Every Fragment,” Jeannie Thib: Body Works, Art Gallery of Mississauga, 1995. Glenn Harcourt, “Andreas Vesalius and the Anatomy of Antique Sculpture,” Representations Special Issue: The Cultural Display of the Body 17 (Winter 1987): 28-61. 3 Cynthia Klestinec, Theatrical Dissections and Dancing Cadavers: Andreas Vesalius and Sixteenth Century Popular Culture, P.h.D Dissertation (Chiciago: University of Chicago, 2001). 4 Vesalius places these sculptural figures within pastoral landscapes. Scenes of rolling hills, distant villages, meadows and trees form a panorama behind all of the muscle-men figures. Cynthia Klestinec explains in her PhD dissertation, Theatrical Dissections and Dancing Cadavers, that throughout the muscle men illustrations, Vesalius has “employed the pastoral and its modal potential, creating a world of strained idealism and interrogating the incommensurability between idyllic existence and mortal decay,” Klestinec, 82. She goes on to explain that “Pastoralisms are habits of mind...Vesalius’ illustrations of muscle men seem to evoke not their mortal reality- they do not appear as actual, decaying corpses undergoing the mutilating process of dissection- but rather the ghostly shadows of the prototypical ancient shepherd combined with Vitruvian, classical proportions of the body, and his idyllic dance,” Klestinec, 84. Polykleitos is also known for developing the technique of Contrapposto, which is used to describe a human figure standing with most of its weight on one foot so that its shoulders and arms twist off-axis from the hips and legs. This gives the figure a more dynamic or alternatively relaxed appearance. The technique of Contrapposto is best understood visually in the muscle men found in Book II of Vesalius’ Fabrica, where complete bodies can be seen in poses similar to those of classical sculptures. Polykleitos was a Greek sculptor in the 5th and the early 4th century BCE. He is known for having developed a sculptural mode of representation in which clearly defined parts are related to one another through a system of idealised mathematical proportions and ratios. 5 Jeannie Thib, “CCCA Artist Profile, Jeannie Thib,” Centre for Contemporary Canadian Art. Accessed December 21, 2012 http://ccca.concordia.ca/artists/artist_info.html?languagePref=en&link_id=956&artist=Jeannie+Thib. 6 Thib. 7 Thib. 2 ARTH 648B-2 Envisioning Digital and Virtual Forms of Exhibitions: The Curatorial Translation of Theory into Practice, 2012 BIBLIOGRAPHY Albano, Caterina. “Visible Bodies.” Literature, Mapping, and the Politics of Space in Early Modern Britain. Ed. Andre Gordon and Bernhard Klein. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press, 2001. 89-106. Baert, Renee. “Signatures on Every Fragment.” Jeannie Thib: Body Works. Art Gallery of Mississauga,1995. Calkins, Casey, James Franciosi and Gary Kolesari. “Human Anatomical Science and Illustration.” Clinical Anatomy 12 (1999): 120-129. Elkins, James. “Art History and Images That Are Not Art.” The Art Bulletin 77:4 (December 1995): 553-571. Harcourt, Glenn. “Andreas Vesalius and the Anatomy of Antique Sculpture.” Representations Special Issue: The Cultural Display of the Body 17 (Winter 1987): 28-61. Heard, Catherine. “CCCA Artist Profile, Catherine Heard.” Centre for Contemporary Canadian Art. Accessed December 21, 2012. http://ccca.concordia.ca/artists/artist_info.html?languagePref=en&link_id=1922&artist= Catherine+Heard. Ingham, Karen. “Art and the Theatre of Mind and Body: How Contemporary Arts Practice is Re-framing the Anatomo-clinical Theatre.” Journal of Anatomy 216 (December 2010): 251-263. Joffe, Stephen N. Andreas Vesalius: The Making, the Madman, and the Myth. Washington: Persona Publishing, 2009. Kemp, Martin. “A Drawing for the Fabrica; and Some Thoughts upon the Vesalius MuscleMen.” Medical History 14 (July 1970): 277-288. Klestinec, Cynthia. Theatrical Dissections and Dancing Cadavers: Andreas Vesalius and Sixteenth Century Popular Culture. P.h.D Dissertation. Chicago: University of Chicago, 2001. Saunders, J., and C. O’Malley. The Illustrations from the Works of Andreas Vesalius of Brussels: with Annotations and Translations, a Discussion of the Plates and their Background, Authorship and Influence, and a Biographical Sketch of Vesalius. New York: Classics of Medicine Library, 1993. Silverman, Mark. “Andreas Vesalius and De Humani Corporis Fabrica.” Clinical Cardiology 14 (1991): 276-279. ARTH 648B-2 Envisioning Digital and Virtual Forms of Exhibitions: The Curatorial Translation of Theory into Practice, 2012 Thib, Jeannie. “CCCA Artist Profile, Jeannie Thib.” Centre for Contemporary Canadian Art. Accessed December 21, 2012. http://ccca.concordia.ca/artists/ artist_info.html?languagePref=en&link_id=956&artist=Jeannie+Thib. ARTH 648B-2 Envisioning Digital and Virtual Forms of Exhibitions: The Curatorial Translation of Theory into Practice, 2012