Hellenistic Period / Intertestamental Works 1 Broad Outline of Topics

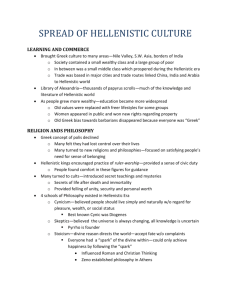

advertisement

Hellenistic Period / Intertestamental Works Broad Outline of Topics: I. II. III. IV. V. VI. VII. I. Intertestamental Period a. Decline of Persian Influence b. Hellenistic Period i. Philip of Macedonia and Alexander the Great ii. Cultural Upheaval for Jews iii. Antiochus IV “Antiochus the Madman” iv. Hasmonean Dynasty Intertestamental Works a. Septuagint b. Deuterocanonical Works / Apocrypha i. Books of Maccabees c. Apocalyptic Literature i. Daniel d. Pseudepigrapha Roman Influence a. Cults within Empire i. Emperor Cult ii. Philosophical Religions 1. Cynicism 2. Stoicism 3. Neo-Pythagoreanism 4. Epicureanism 5. Hedonism iii. Mystery Religions 1. Cult of Isis 2. Cult of Mithras 3. Eleusinian Cult An Approach to Understanding the Gospels Gospel Interpretation The Synoptic Problem Historical-Critical Methodology Intertestamental Period Intertestamental period is identified as the period of history marked either by the Persian occupation (532-332) or the Greek occupation (332-164). This period is sometimes referred to as the 400 Silent Years, not because not much happened but rather, scholars say, because the period of prophecy had ended. a. Decline of Persian Influence 1 Hellenistic Period / Intertestamental Works By 334 BCE, when Alexander the Great marched his armies across the Hellespont in order to seize the Persian Empire for himself, the Greeks and Persians had been at war for a number of generations. Darius III, king of Persia was defeated, first at Granicus, then at Isssus and finally at Garugamela in 331 BCE. When Alexander died in 323 BCE, he had brought the entire Persian Empire under his thumb. The Jews of Judah were rather insignificant compared to these world powers. However, during Persian occupation, there had been three major changes in the post-exilic Jewish community: 1. In place of an independent monarchy with its “sacred king” was a temple-state governed by the high priest and a priestly aristocracy subject to a foreign power. 2. While prophecy continued (Haggai and Zechariah; see Zech 13:2-6), there was also concern for its decline (1 Macc 9:27) 3. The growing centrality of the Torah and the necessity of its interpretation for the affairs of everyday life In summary, Israel was under the control of the Persian Empire from about 532-332 B.C. The Persians allowed the Jews to practice their religion with little interference. They were even allowed to rebuild and worship at the temple (2 Chronicles 36:22-23; Ezra 1:1-4). This period included the last 100 or so years of the Old Testament period and about the first 100 years of the Intertestamental period. b. Hellenistic Period The death of Alexander the Great in 323 bce led to a bitter political power struggle among his Macedonian generals. In the period after 301, four distinct Hellenistic kingdoms emerged: 1. The Ptolemaic Kingdom in Egypt and north African coast, established by Ptolemy I of Egypt 2. The Seleucid Kingdom established by Seleucus I of Syria 3. The Antigonid Kingdom (Macedonia and parts of Greece) 4. The Attalid Kingdom in western Asia Minor Meanwhile, a fifth power was rising over the western horizon: Rome. The Egyptian Ptolemies allowed the Jews relative independence during the 3rd century. In 198 bce, however, the Seleucids gained control of Palestine. At first, the Jews welcomed this Syrian presence. However, in 190 bce, the Romans defeated the Seleucids and forced them and their colonies to pay a huge compensation. Then in 175 bce, Antiochus IV Epiphanes, who claimed to be divine (Epiphanes in Greek means “god manifest”), took the Seleucid throne. He sought to enforce Hellenization throughout his empire and to raise the indemnity demanded by Rome. The Jewish urban aristocracy complied. Some priests began to bid for the High Priesthood. They also tried to carry out a “Hellenistic reform,” that is, to abolish the ancestral laws and 2 Hellenistic Period / Intertestamental Works transform Jerusalem into a Hellenistic city-state. These events produced an internal Jewish conflict that had momentous results. Antiochus the Madman Rumors of Antiochus’ death prompted a civil war amongst the priestly families. Antiochus, who was in fact not dead, misinterpreted the unrest as a revolt against Hellenization. On his return to Jerusalem to squelch the overthrow, he had 80,000 Jews killed. His response also was to forbid Temple sacrifice, destroy Torah scrolls and force everyone to worship Greek gods. He also entered the Holy of Holies in the Temple and set up pagan idols there and sacrificed pigs upon the altar ("abomination of desolation" mentioned in Daniel 8 and 11; Daniel 8:8-13 describes this time). Antiochus established the following laws in Jerusalem: Jews could not assemble for prayer; Observance of the Sabbath was forbidden; possession of the Scriptures was illegal; circumcision was illegal; it was illegal to refuse to eat hogs or any other food that was prohibited by the Mosaic Law; it was illegal not to participate in the monthly sacrifice honoring Antiochus. This involved eating of the meat that had been offered in sacrifice. Antiochus Epiphanes’ career with respect to Palestine is also recorded in 1 and 2 Maccabees, and “predicted” in Daniel 11:21-35" 1 and 2 Maccabees are deuterocanonical / apocryphal and are valuable as historical accounts. Maccabean Revolt: The Jewish response to forced Hellenization was a war of social, religious, and national liberation. The initial phase was the Maccabean Revolt (167-164 bce). (Story of Mattathias and his sons, and the Hasidim – see 1 Macc 2) Rededication of the Temple – “Festival of Lights” = Feast of Hanukkah Hasmonean Dynasty – Maccabean family, a priestly Jewish family, rule over Judea autonomously ridding themselves of foreign domination. This rule, 167-63 bce, will be the last time that Jews control their own land until 1948, when post-WWII state of Israel is established. Another feature of the Hasmonean period is the rise of various Jewish sects: Sadducees, Pharisees, and Essenes. In general, two trends dominated the Greek period in Palestine (332 – 63 bce): 1. The gradual Hellenization of the Jewish aristocracy 2. The reaction of the religiously conservative peasant classes to forced Hellenization, resulting in the Maccabean Revolt and the independent Maccabean (Hasmonean) dynasty. Their banner was “zeal for the Law.” II. Intertestamental Works 3 Hellenistic Period / Intertestamental Works Most of the books written between the last book of the Hebrew Bible and the first book of the New Testament did not make it into the canon (Daniel is an exception). These books still have importance for biblical studies and are regarded as deuterocanonical or apocryphal depending upon to whom you speak. Books recorded during this time are generally included in most Catholic and Orthodox Bibles, but only in a few Protestant Bibles. a. Septuagint Alexander was a student of Aristotle, and so was well educated in Greek philosophy and politics. He required that Greek culture be promoted in every land that he conquered. As a result, the Hebrew Scriptures were translated into Greek, becoming the translation known as the Septuagint. Most of the NT references to Hebrew Scripture use the Septuagint phrasing. This translation of the Hebrew Canon included more books than earlier collections. The extra books were omitted by Jewish religious leaders when they reassessed their canon at the Council of Jamnia in 90 CE. Legend of the Septuagint Ptolemy hired and housed 72 rabbis, according to the Letter of Aristeas. Each separately translated the Hebrew Scriptures in 70 days time. Their translations matched perfectly. Because of this, the translation was known as the "Septuagint" (Latin: "Seventy") and is often abbreviated by the Roman numeral LXX. This was to become the most popular and widely used translation of the Hebrew Bible. b. Deuterocanonical / Apocryphal Works A Jewish council was held in Jamnia in approximately 90 CE that determined the canon of the Hebrew Bible for Jews. The council removed those works from the Septuagint that were not originally written in Hebrew. In the 16th c, Protestants would adopt this Jewish canon but Catholics and Orthodox Christians would hold to the older collection that included more works. Titles 1 and 2 Esdras, Tobit, Judith, Additions to the Book of Esther, Wisdom, Sirach (Ecclesiasticus), Baruch and the Letter of Jeremiah, Additions to Daniel (Prayer of Azariah, Song of the Three Hebrew Children, History of Susanna, Bel and the Dragon), the Prayer of Manasseh, and 1 and 2 Maccabees Books of Maccabees Four Jewish books named after Judas Maccabeus, the hero of the first two . Books 1 and 2 provide a vivid account of Jewish resistance to the religious suppression and Hellenistic cultural penetration of the Seleucid period (175 - 135 BC). 1 Maccabees is generally considered historically more reliable where the two are parallel. 2 Maccabees is of value because it 4 Hellenistic Period / Intertestamental Works describes in greater detail the Hellenistic reform and the origin of the revolt prior to the emergence of the Maccabees, and because it provides greater insight into the history of the Jewish religion. The First Book of the Maccabees This book provides a history of the Maccabean revolt from the accession of Antiochus IV Epiphanes in 175 bce until the death of Simon, one of the leaders of the Jewish resistance and then high priest and ethnarch, in 132 bce. The struggle is the point of a clash between Hellenistic culture and the exclusivism of Judaism. The book was composed in Hebrew, sometime after the death of John Hyrcanus, Simon’s son, in 104 bce but before the beginning of Roman rule in Palestine in 63 bce. It is the primary source for the history of the period. Purpose of 1 Maccabees The purpose of 1 Maccabees seems to be to legitimate the Hasmoneans (Maccabees) as rulers of Palestine in consequence of the contribution made to the liberation of Judea from Seleucid rule by the founders of the dynasty, Judas, Jonathan, and Simon, the sons of Mattathias. Maccabee means ‘the hammer’ in Hebrew and is the nickname of Judas, possibly because of the hammerlike blows he dealt the enemy. It is applied more generally to the three brothers as well as to the revolt they led. The Second Book of the Maccabees This book provides a second history of the Maccabean revolt, written from a different perspective. Where 1 Macc is concerned to praise Judas, Jonathan, and Simon for their role in the liberation of the Jewish people from Seleucid oppression, 2 Macc focuses upon the insult to the Temple and its cult, for which it holds the Jewish Hellenizers primarily responsible. The period covered by 2 Maccabees is about 180-161 bce Difference in Literary Style 2 Maccabees is generally termed a ‘pathetic’ history (from Gk. pathos, ‘emotion’ or ‘feeling’) because of the way in which it dwells upon the deaths of the righteous martyrs or the wicked king in a manner designed to evoke compassionate or contemptuous pity in the reader c. Apocalyptic Literature Another genre that emerged during the period of Hellenization is that of apocalyptic. The Jews adopt this Greek literary style which is especially evident in the Book of Daniel. The Book of Daniel is a highly symbolic work that interprets the people’s political, social, and religious crises. The adjective form, apocalyptic, is a modern label for end-time literature associated with identifiable religious and sociological perspectives. Apocalypticism applies to the thought world or worldview of the communities that gave rise to apocalyptic literature. It was mostly written 5 Hellenistic Period / Intertestamental Works during times of political persecution, intended to encourage perseverance by revealing the destruction of the wicked and revealing the glorious future that awaited the faithful. In its social, political, or economic alienation the community constructs an alternate universe where eventually it will triumph. This alternate universe comes to expression in apocalyptic literature Characteristics of the Literature Paired opposites pitted against each other o Good and evil (exclusivism) o Heaven and earth (cosmic dualism) o This age and the next (chronological dualism) o Sons of light vs. Sons of darkness (ethical dualism) Reports of visions from God that explain how the faithful will overcome evil (symbolic language) Often speaks of life after death (eschatology) New leader who will rule on behalf of God (limited theology) Ultimately the goal of the author was to inspire hope in the midst of what appeared to be a lost cause. Exclusivism, Cosmic dualism, Chronological dualism, Ethical dualism, Use of Symbolic Language, Eschatology, Limited Theology, Hope Daniel: The Literary World Daniel is a book of heroes and apocalyptic visions. It is intended to inspire hope and courage among Jews living within monstrous empires they considered the personification of evil. Daniel 7 contains Daniel's vision of four empire beasts that are judged for their deeds before the Ancient of Days in the heavenly courtroom. The book can be divided more or less cleanly into two main parts based on content: Chapters 1-6: contain six tales of Jewish heroism set in the late 7th and 6th c BCE; Chapters 7-12: contain four apocalypses which Daniel narrates in the first-person. Part 1 – Chapters 1-6 This part contains some of the most popular stories in the Hebrew Bible: Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego in the fiery furnace Daniel in the lion's den The handwriting on the wall Tales had moral and spiritual lessons with special application to Jews living in the Diaspora. The message of the Hero Tales seems to stress that fidelity to Mosaic Torah brings divine reward. Also, ultimately the evil kingdoms of this world will crumble before the kingdom of God, for Yahweh orders history. 6 Hellenistic Period / Intertestamental Works Part 2 – Chapters 7-12 - Apocalypses (7-12) The four beasts and the Son of Man (7) The ram and the goat (8) Gabriel interprets Jeremiah's prophecy of the seventy weeks (9) Vision of future history (10-12) Daniel: The Historical World Stories set around the time of the Babylonian exile and the tales may have originated at that time. However, the apocalypses of chapters 7-12 betray a much later setting. The history they (fore-)tell culminates in the time of the Maccabees, specifically the years of Antiochus IV. The evidence strongly suggests that the apocalypses were written around 165 B.C.E. Although many Jews accommodated and assimilated to Hellenism, others opposed any sort of compromise III. d. Other Works Emerging from this Period - Pseudepigrapha Other works emerging from this period of Hellenization include what is known as pseudepigraphal works meaning "books with false titles." These works are books similar in type to those of the Bible whose authors gave them the names of persons of a much earlier period in order to enhance their authority. They are important for the light they throw on Judaism and early Christianity. These works can also be written about Biblical matters, often in such a way that they appear to be as authoritative as works which have been included in the many versions of the Judeo-Christian scriptures. Examples: i. Epistle of Jude, for example, reflects knowledge of Enoch and the Assumption of Moses. ii. Letter ofAristeas offers us the legend of the Septuagint (6 members each from the 12 tribes of Israel – 72 – translate the HB into Greek at the request of the Egyptian, presumably Ptolemy II Philadelphus, in 72 days). Roman Influence: Religions in the First Century Greco-Roman World a. Great variety of pagan cults that emphasized ritual and sacrifice over worship of the divine Members of cults would appease their chosen divinity to ensure health, wealth, prosperity, favors, etc. To the Romans, religion was less a spiritual experience than a contractual relationship between humankind and the forces which were believed to control people's existence and well-being. Endorsed by the Empire i. Behaviors associated with cultic devotions were endorsed by the empire ii. State religious rituals were believed to protect the empire as a whole iii. Domestic rituals, where families conducted rituals and sacrifices to local deities, had the same purpose but, led by the father of the house, were meant to protect the household 7 Hellenistic Period / Intertestamental Works b. Varieties of Cults i. Emperor Cult ii. Philosophical Religions iii. Domestic / Local Cults iv. Mystery Cults c. Emperor Cult i. The emperor or ruler cult started as an expression of gratitude to benefactors and became an expression of homage and loyalty. ii. It was a matter of giving to the ruler, not getting from him (except indirectly) iii. In other words, supernatural assistance was not expected from him in the same way it was sought from the gods. iv. The religious meaning was not as great as its social and political importance where it served to testify to loyalty and to satisfy the ambition of leading families. v. Has special importance for the study of early Christianity because it formed the focal point of the early church's conflict with paganism d. Philosophical Religions i. The goal of Freedom lay at the heart of most of the religious movements and philosophies of the world, each propounding some special way to achieve it. ii. Cynicism iii. Stoicism iv. Neo-Pythagoreanism v. Epicureanism vi. Hedonism e. Cynicism i. Pursued freedom from cares of life by seeking only what was available in nature; typically eschewed civic affairs ii. Rather than a 'school' of philosophy, it was an informal group of philosophers with certain attitudes and unconventional behaviors who either called themselves Cynics or were so-called by others. iii. Cynicism involves living the simple life in order that the soul can be set free. iv. By eliminating one’s needs and possessions, one can better concentrate on the life of philosophy. f. Stoicism i. Emphasized self-control and rational examination of the order in the world ii. Minimized relying on nature and focused on human understanding instead iii. The founder of stoicism is Zeno of Citium (333-262) in Cyprus. iv. He lectured his students on the value of apatheia, the absence of passion, something not too different from the Buddhist idea of non-attachment. g. Neo-Pythagoreanism i. Revival of ancient Pythagoreanism (dating back to 5th c BCE) 8 Hellenistic Period / Intertestamental Works ii. Freedom for neo-pythagoreanists meant capitalizing on Pythagoras’ discoveries iii. Mathematical basis of natural elements as well as many human concepts (music for example); calculated movement of stars; invented geometry iv. Harmony was thus the secret to life and freedom within life v. Disharmony came from that which was not associated with numbers and proportions, i.e., the bodies appetites and passions h. Epicureanism i. Sought freedom by withdrawal from the uncertainties of life ii. Emphasized the material realm of reality and were often hedonists to some extent in that they emphasized and valued material and physical pleasures iii. Epicureans were not Hedonists because Epicureans would seek pleasure by eliminating bodily and mental suffering (so their methods differed) iv. Drinking wine is pleasurable (both would agree) but Epicureans would not over-indulge as that would lead to pain/suffering later i. Hedonism i. The philosophy of Hedonism is quite simple: ii. Whatever human do, we do it to gain pleasure or to avoid pain. iii. Pleasure is the ultimate good, and the achievement of pleasure the only virtue. iv. They regard morality as merely a matter of cultural customs and laws, (ethical relativism is our term for this). v. Science, art, civilization in general, are good only to the extent that they are useful in producing pleasure. j. Domestic / Local Cults i. Analogical to the Emperor Cult where the emperor was the head of the sociocultural family, domestic cults quite common throughout ancient Rome ii. Every family belonged to a clan, and these clans themselves had special patron gods and corresponding rites. iii. The worship of these spirits is what truly defines Roman religion, and what really separates it from the sister religion of Greek paganism. k. Mystery Cults i. A mystery religion is a religious organization or cult which is focused mainly on a single deity. ii. This deity usually has something which it can offer to the individual member of the society. iii. The distinguishing characteristics of a mystery religion are the focus on the individual, a sense of community and generally a salvation theme. iv. Details of the cults remain a mystery to us as the devotees were successful in keeping them secret. l. Varieties of Mystery Cults i. Isis 9 Hellenistic Period / Intertestamental Works ii. Mithras iii. Eleusinian Mysteries iv. Cult Figures m. Characteristics of the Mystery Cults i. The cultic behaviors probably included some singing or dancing during a reenactment of the myth. ii. Initiation rites were ceremoniously conducted in secret. iii. The rites most likely included purification through sacred baths in streams and the sea as well as three days of fasting and an unknown central rite. iv. By joining, the members were promised some advantages in the afterlife, as in any good salvation cult. n. Competition Amongst Mystery Cults i. During the early Empire, the cults of Mithras and Isis were very popular, though were later driven nearly to extinction by Christianity. o. Temple Inscriptions i. Thanks to Minerva, that she restored my hair. ii. Thanks to Jupiter Leto, that my wife bore a child. iii. Thanks to Zeus Helios the Great Sarapis, Savior and Giver of wealth. iv. Thanks to Silvanus, from a vision, for freedom from slavery. v. Thanks to Jupiter, that my taxes were lessened. vi. I pray for the safety of my colony and its senate and people, because Jupiter Best and Greatest by his numen tore out and rescued the names of the decurions that had been fixed to monuments by the unspeakable crime of that most wicked city-slave who refused to work... An Approach to Understanding the Gospels (the following draws from: Barr, David, New Testament Story: An Introduction, 4th ed., (Wadsworth, Cengage: Belmont, CA), 2009. IV. Understanding how to interpret the Gospels a. First, it is important to know exactly what the word, gospel, means. i. Old English, godspel (good spell) where “spel” refers not to magic but to “story” ii. A gospel, then, is a good story iii. Greek term for gospel, “euangellion” or “evangellion” means a good announcement iv. Another clue is that we have four Gospels which implies that, while they are ultimately rooted in the events of Jesus’ life, each author told the story slightly differently for a variety of reasons b. Second, when we recognize that there are differences in the Gospels, we might first struggle with which one is “true.” c. This struggle is best addressed by recognizing how we may go about interpreting these stories 10 Hellenistic Period / Intertestamental Works V. i. While the Gospel narrative ARE rooted in the events of Jesus’ life in first century-Palestine, what has been handed down to us is not meant to be a factual detailed history simply recounting the events as they actually happened. ii. Rather we gave Gospel narratives shaped by: 1. Author’s purposes 2. Plotting devices 3. Ancient views of how humans work 4. Readers’ expectations 5. The overarching views of the real meaning of the Gospel story d. A Case in Point: The Empty Tomb Stories i. The four accounts of the empty tomb story vary in details so much that some have even questioned if they all refer to the same event ii. We will proceed not with a focus so much on how to reconcile these differences but rather to examine how biblical scholars have interpreted these differences. Gospel Interpretation a. The ancient approach to dealing with the apparent contradictions and differences within the gospel narratives usually favored one of three solutions. i. Elimination ii. Combination iii. Harmonization b. Elimination i. Some groups sought to only accept one gospel as legitimate; there were supporters for each of the four that eventually made it into the canon ii. This reductive attempt to achieve unity by rejecting multiple gospels never gained wide support in the churches. c. Combination i. Tatian, a church leader in the year of about 170, attempted to solve the problem by combining the four Gospels into one blended account. ii. This work was called the Diatessaron, which translates as “Through the Four.” iii. Although this was a very ingenious way to find unity, it too was not without problems. 1. He hides some problems a. The Lukan motivation of coming to anoint the body ignores the Matthean version that they come only “to see the tomb” b. Tatian’s version also ignores the Johannine version in which the anointing was done before burial c. He also distorts only details like i. When and how to move the stone ii. Angels or men present iii. Return to Galilee or not iv. To tell others or to keep silent 11 Hellenistic Period / Intertestamental Works VI. d. Irenaeus, bishop of Lyon, asserted that there must be four gospels by insisting that there is really only one Gospel but these four highlight differences that are necessary for humanity to have diversity in the unity e. Augustine’s Harmony of the Gospels is a good example of this intellectual balance of a fourfold gospel underlying the Gospel story which basically holds that each Gospel writer chose to highlight what another Gospel writer minimized or ignored i. A problem with this approach is not so much that is isn’t possible to harmonize the gospels this way but rather that it may distort the way the story should be understood by each particular gospel writer. f. The Modern Approach: Criticism i. The term “criticism” here refers to being able to discern, to make distinctions. Thus, a critic is a person of discernment. ii. Criticism involves asking disciplined questions designed to elicit the information we want to know. iii. Modern Biblical Criticism may be traced back to the Enlightenment in the 18th century when it was intertwined with the 19th century discovery of the modern idea of history. iv. But the gospels are not to be read as historical documents as we understand history; rather we must be sensitive to the original authors’ intentions and to whom the author tailored his message, i.e., knowing the audience too. Synoptic Problem a. Once biblical interpreters faced the issue of interdependence head on, i.e., letting go of the idea that the Gospels were written in the order as they appear in the Bible, a new problem emerged. i. Three of the gospels were so very much alike, they each obviously were related to the other two. But which one came first? 1. This problem is known as the synoptic problem. 2. The three that look and sound so much alike are Matthew, Mark, and Luke. ii. Scholars studied them to determine which came first on the assumption that knowing the earliest Gospel gets us closer to the roots of the story iii. Virtually all scholars agree that Mark was written first, even though it is not the first gospel in the canon. b. Excursus on Markan Priority i. The subject matter of Mark is more extensively found in Matthew and Luke than either of MT or Lk is found in Mark. ii. In all but three cases, when a Markan passage is missing in Mt or Lk, it is found in the other one. This implies that Mark is the common element for both Mt and Lk iii. The order of Mark is more clearly reflected in Mt and Lk than the order of either of these is reflected in Mark. iv. Mt and Lk improve upon some awkward expressions found in Mark 12 Hellenistic Period / Intertestamental Works v. It is simply easier to imagine Mt as an expansion of Mark as opposed to Mark being an abbreviated version of Mt or Lk vi. Another tradition emerges when scholars note that Mt and Lk share a remarkable amount of material that is not found in Mark 1. The Q Source is theorized: Q is the symbol for the German word Quelle, meaning source. 2. The theory is that the authors of Mt and Lk appealed to another written source that no longer exists vii. Where Mt and Lk do not agree with either Mark or each other, scholars speculate that each offered new and unique material to their telling of Jesus’ story viii. A diagram depicts this Four-Source Theory VII. Historical-Critical Methodology a. Variety from the Oral Transmission of the Tradition i. Form Criticism 1. Attempts to determine the form of the tradition (legend, hymn, curse, lament, myth, example story, folk tale, etc.) and to determine the typical situation in which that form would have been used (hymns in worship; example stories in educating children; myths to offer meaning) 2. Form criticism is a way of analyzing how later writers/editors recorded the stories that had been part of more ancient history and preserved orally until they were eventually recorded 3. As used by NT scholars, form criticism seeks to analyze how the Gospels emerged from oral traditions in a variety of settings to smoothly presented narratives as offered by Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John a. Because the first three gospels are so similar, their oral traditions and settings were most likely highly related to each other b. Because John’s gospel is so different, we can assume another tradition existed beside that one that inspired the synoptic gospels b. Variety from the Editing Process i. Redaction Criticism 1. By means of this analysis of editorial and compositional techniques, critics hope to discern the particular perspective of each writer, what was each author’s theology. 13 Hellenistic Period / Intertestamental Works 2. Redaction critics discovered that each writer had a design that shaped the story of Jesus a. Each gospel writer was shaping the Jesus story for a particular audience and for a particular emphasis on Jesus’ identity c. Variety from the Writing of Literature i. Studying narrative means honing skills to understand how the author shows meaning as opposed to explicitly saying what is meant. 1. E.g., a story is more engaging than a manual ii. Literary criticism of biblical narrative applies many of the techniques used by literary criticisms in general 1. The logical unity of the story’s actions 2. The nature of its world 3. The significance of its characters 4. Analysis of the tensions in a story a. E.g., the narrative role fulfilled by the women or disciples may vary greatly among the different Gospels b. Their characters may require a certain response dictated by the larger narrative iii. Aristotle’s distinction between history and poetry provides an analogy on a basic level: 1. Just as poetry is concerned with universals and history is concerned with particulars, art reflects and interprets and life simply is. 2. Applied to our study of the Gospels then, the Gospel writers artfully interpret Jesus’ life iv. Compare the 3 versions in Acts of the Gospel being delivered to the Gentiles 1. Acts 9:1-30; 22:1-21; and 26:12-20 2. Each version adds more thus building its significance and illustrating Luke’s ultimate goal, namely, Paul was commissioned to preach to the Gentiles a. Acts 9: commissioning from Ananias 9:15 b. Acts 22: Paul receives divine commissioning while praying in Temple c. Acts 26: Paul sees risen Jesus d. Variety Understood as Oral Performance i. Scholars are becoming more sensitive to the differences in thinking and perspectives associated with oral cultures as opposed to literary cultures 1. Models of transmission are different 2. Where we think more linearly – there was one original telling from which all subsequent versions emerged – oral cultures are more complex 14 Hellenistic Period / Intertestamental Works a. Many versions existed simultaneously and the authors ultimately drew from a variety of sources b. The gospels, too, would influences “sources” c. The idea here is to see the stories more as an interconnected web where all versions impact each other e. Our Approach i. Rely on the findings of Source Criticism which asserts Markan priority ii. Form Criticism asks two kinds of questions: 1. What is the literary form of a particular unit? 2. What is the pre-Gospel history of such a unit? iii. Redaction Criticism questions focus on what each writer has done to shape the traditions used 1. Caveat – our emphasis in studying the editing process will not be on the writers but on their respective presentation of Jesus iv. Literary Criticism 1. Will focus on the plots of the stories 2. Portrayal of characters 3. Images 4. Motifs 5. Points of View 6. Structure v. Historicist vs. Literary View 1. Historicist is perhaps too simplified because it assumes to view the story as a direct account showing what actually happened as if the story were simply a window into the past 2. Literary View may give us a glimpse into what actually happened but the writer has styled the account and used literary tools such as plotting, characterization, points of view, symbolism, etc., to provide a mirror reflecting the past. 15